Neuberg, S. L., & Schaller, M. (in press).

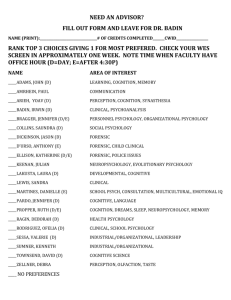

advertisement