ASCA Newsletter - American Swimming Coaches Association

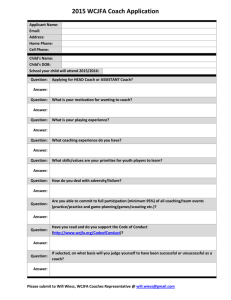

advertisement