PreHealth Handbook - Seattle University

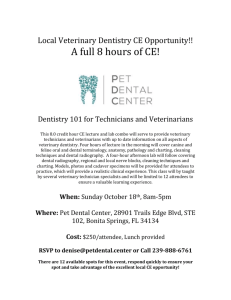

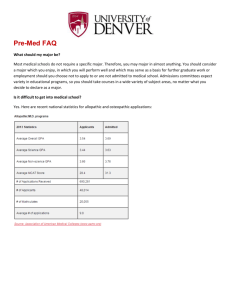

advertisement