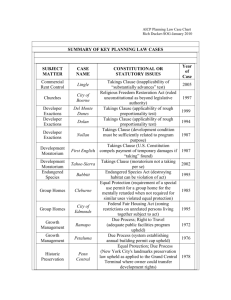

Regulatory Takings and Land Use Regulation

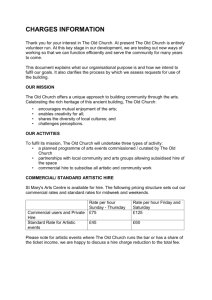

advertisement