CONSOLIDATION ACCOUNTING

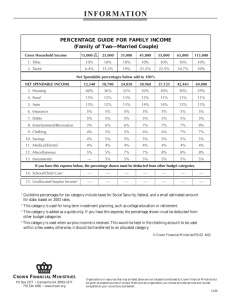

advertisement

CONSOLIDATION ACCOUNTING:

A HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF

FINANCIAL REPORTING STANDARD FRS-37

AND

SECTOR-NEUTRAL

CONSOLIDATION ACCOUNTING

FOR CROWN FINANCIAL REPORTING

BY THE

NEW ZEALAND GOVERNMENT

CONSOLIDATION ACCOUNTING:

A HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT

OF

FINANCIAL REPORTING STANDARD FRS-37

AND

SECTOR-NEUTRAL CONSOLIDATION ACCOUNTING

FOR

CROWN FINANCIAL REPORTING

BY THE

NEW ZEALAND GOVERNMENT

A thesis submitted to the University of Canterbury

in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

by

SONJA PONT NEWBY

University of Canterbury

2006

DECLARATION

I certify that this work has not been submitted to any other university or institution.

The extent to which I have availed myself of the work of others is acknowledged in

the text. Sources of information are listed in the reference list.

Sonja Pont Newby

December 2006

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to formally acknowledge the financial and other support provided by the

Treasury of the New Zealand Government, the PhD scholarship awarded by the

Institute of Chartered Accountants of New Zealand (then known as the New Zealand

Society of Accountants), the doctoral research support funded by the Accounting

Association of Australia and New Zealand, and the University of Canterbury PhD

scholarships together with the other assistance granted through the Department of

Accounting, Finance and Information Systems of the University of Canterbury.

I am deeply grateful to Sue Newberry for her unfailing encouragement and guidance

and wish to pay tribute to her professionalism, kindness and wisdom which have

helped me so much in bringing this work to life - thank you Sue.

I also wish to thank my family and friends for their patience and caring, especially

my dear Warren who has been magnificent throughout and made it all possible, and

of course my wonderful mother Maria, and my little darlings Jasmine, Sarah and Ben

- thank you all for sharing this journey with me.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract

1

Chapter One:

Introduction

2

Chapter Two:

Research Method

7

Chapter Three:

Antecedent World:

Consolidation Theory and Practice

32

Antecedent World:

Initial Conditions in Government

Financial Management

57

Antecedent World:

Public Finance Act and

Crown GAAP Consolidation

76

Chapter Four:

Chapter Five:

Chapter Six:

Chapter Seven:

Chapter Eight:

Chapter Nine:

Chapter Ten:

Antecedent World:

Establishment of the Sector-Neutral Platform

108

The Event Begins:

Developing Sector-Neutral Consolidation

148

During the Event:

Waiting for International Developments

189

Subsequent World:

Events Subsequent to Approval of FRS-37

209

Summary and Conclusions

222

References

238

ABSTRACT

This thesis provides a narrative account of the development of the sector-neutral

financial reporting standard FRS-37: Consolidating Investments in Subsidiaries,

applicable to both government and the private sector in the New Zealand institutional

setting. The protracted promulgation of this accounting standard over eight years is the

research event of interest.

New Zealand’s overhauled Public Finance Act 1989 introduced a requirement for the

Crown to produce accrual consolidated accounts prepared in accordance with GAAP.

Consolidation GAAP was vague however and a preferential modified equity accounting

method was used throughout the development period of FRS-37. This seemed

contradictory to the sector-neutral GAAP stance since the method was not allowed in

the private sector. After FRS-37 was approved the Crown was required to present

financial reports incorporating its interests in State Owned Enterprises and Crown

entities on a fully consolidated basis. Subsequently international developments in

government accounting put the viability of so-called NZ GAAP into question. The

research objective was to better understand what happened.

The historical method of Porter (1981) is used to trace the changes shaping the event.

This involved consideration of antecedent and subsequent conditions around the event

as well as its internal development. The event of FRS-37 commenced in September

1993 following the establishment of the Accounting Standards Review Board by the

Financial Reporting Act 1993 which necessitated the development of a sector-neutral

consolidation standard for approval, and concluded around October 2001 when FRS-37

was approved. The comparative antecedent period commencing around 1985 indicated

the contextual conditions leading into the event, and the subsequent period to 2006

following FRS-37’s implementation showed changed conditions that confirmed the

event’s conclusion.

The contribution of this thesis is that it documents the defined event and explains what

happened, offering understanding of the issues around consolidation accounting, sectorneutral GAAP and public sector financial management.

CHAPTER ONE:

INTRODUCTION

Chapter One Introduction

Chapter One introduces the research issue and the research methodology applied to

the issue. It then provides an overview of the contextual setting for the research

issue, as suggested by the methodology. It concludes with an outline of how the

subsequent

chapters are arranged.

Introduction to the Research Issue and Methodology

This research was motivated by the unexpected delay in the development and

approval of a standard on consolidation accounting following public sector reforms

in New Zealand. While the thesis is concerned with the accounting issue of

consolidated financial reporting it also considers the wider contextual setting of the

standard’s development and implementation to better understand the issue.

The reforms included a requirement introduced by the Public Finance Act 1989 that

the Crown must adopt generally accepted accounting practice (GAAP) for its

financial reporting. GAAP for the Crown was initially defined in terms of accounting

practices recognised by the New Zealand accounting profession as being appropriate

and relevant for the reporting of financial information in the public sector. At that

time there was no GAAP on consolidation specifically for the Crown and GAAP was

represented in the current standards that had been issued by the accounting

profession on the basis they offered authoritative support of best practice.

The current standard then on consolidation accounting, SSAP-8 (1987): Accounting

for Business Combinations (SSAP-8) had been developed for companies in the

private sector and had been in force since 1 January 1988. It required parent

companies to present accounts including subsidiaries on a fully consolidated basis.

These terms were defined by reference to the provisions of the Companies Act 1955

wherein control was a function of equity ownership (barring fiduciary situations) and

a company holding more than half in nominal value of the equity share capital in

another company normally satisfied the definition of parent which in turn established

Chapter One: Introduction

3

the status of the subsidiary and the need for group accounts.

Since most of the Crown’s investments were 100% owned they appeared to satisfy

the definition of subsidiary. Prior to the Crown’s new reporting requirements coming

into effect SSAP-8 was amended in October 1990 to specifically exclude the Crown.

GAAP for the Crown then became ambiguous. There were issues around the

meaning of control and an argument was raised that full consolidation of the state

owned enterprises (SOEs) was not appropriate despite the Crown holding 100% of

their equity, since they had been established with an intent of statutory independence

from the Crown.

The Office of the Auditor-General (OAG) increasingly disagreed with this

interpretation of GAAP. It seemed a contradiction that New Zealand claimed to have

followed GAAP and yet would not follow the GAAP practice of full consolidation

notwithstanding the Crown’s exemption from SSAP-8, and instead adopted a

preferential practice that was unavailable to the private sector. The ambiguity

persisted for some years whilst standards-setters worked on the issues with a view to

revising the standard.

Following international trends a statutory accounting standards approving body,

named the Accounting Standards Review Board (ASRB), was created by the

Financial Reporting Act 1993 which came out of a review of the corporate

environment subsequent to the share market crash of 1987. Under the new

arrangements the accounting profession would continue to formulate accounting

standards which then needed to be submitted to the ASRB for statutory approval,

thus giving them the force of law deemed necessary as a conclusion of the corporate

environment review. The inclusion of the public sector and specifically the

government within the scope of ASRB authority was a last minute legislative

change. In this way the sector-neutral platform was introduced and the profession’s

standards-setters worked on developing accounting standards that could be approved

as applicable across all sectors where appropriate.

Soon after its establishment in 1993 the ASRB quickly approved most of the

previous body of accounting standards produced by the profession, however

exceptions to this were the existing standards on accounting for fixed assets,

depreciation, and consolidation accounting. This thesis focuses on consolidation

Chapter One: Introduction

4

accounting. Supposedly in a sector-neutral environment which required companies to

include their subsidiaries in group accounts, government should likewise produce

consolidated financial statements following the same rules as in the private sector.

Until the ASRB approved a standard however a state of limbo prevailed wherein

companies and their officers were legally bound to produce group accounts under the

companies legislation and were bound to apply full consolidation following SSAP-8

but the Crown was exempted from this requirement and applied a form of modified

equity accounting that was not allowed in the private sector.

It took eight years of intensive work by the profession’s standards-setting groups

before the standard FRS-37: Consolidating Investments in Subsidiaries (FRS-37) was

finalised and made ready for ASRB approval in October 2001. This was clearly

much longer than had been required for most of the other standards to be approved,

and the new rules on consolidation once approved largely ratified existing

commercial practice. The difficulties experienced in the development of the standard

seemed to reflect broader institutional factors and the need to attain sector-neutrality.

This thesis attempts to provide a fuller understanding of the consolidation issue by

setting out what happened during the development of FRS-37. A historical research

method is applied which brings to light material not previously made public and

presents it using a structured framework based on Porter (1981) so that the various

events may be better appreciated and understood in their wider context.

Overview of the Contextual Setting

The global economic order established after World War II was clearly strained from

the mid-1960s. In an environment of increasing trade competition and concerns

about the international monetary system following the US rejection of the gold

standard in 1971, efforts commenced to reform this global economic order.

These reforms drew on the increasing interest in micro-economics, macro-economic

theories having become viewed as disconnected from practical effects and therefore

of limited use for achieving change (Jones, 1992a). Christenson et al (2007) report

that the development of detailed rules for policy purposes became popular and that,

from about 1967, the World Bank began to promote micro-economic reforms to its

Chapter One: Introduction

5

member countries. Over time these reforms developed into what became known as

the Washington consensus, advocating a range of structural and economic

adjustments including public sector reforms. The public sector reform component

favoured the privatisation of services previously provided by the public sector, which

potentially offered significant trading opportunities in services ranging from the

generation and supply of electricity to health, education and social welfare.

One significant technical difficulty arising from these reforms was the problem of

obtaining internationally comparable and relevant economic data. According to

Christensen et al (2007), the fact that the reform ideas derived from micro-economics

but required comparable detailed financial information required the co-operation of

both economists and accountants to develop this system. Indeed, a view developed

that a single internationally standardised financial system could meet both macro and

micro-economic policy purposes and could apply to all sectors of the economy.

Christenson et al (2007) observed that key features of the reforms advocated by the

World Bank in 1967 were similar to features observed in the New Zealand public

sector financial management systems today.

These reforms also affected the accounting profession which clearly had perceived

the need to develop at a global level: the formation of the International Accounting

Standards Committee (IASC) having occurred in 1973, followed by the

establishment of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) in 1977.

Evidently the accounting bodies perceived a danger that if they did not establish their

relevance and role quickly at this global level then governmental agencies might not

see a role for accountants, and therefore engage in setting the international financial

reporting rules themselves (Christenson et al, 2007). Further, given the developments

in trade liberalisation and the potential for privatisation of a range of government

services, there was scope for major opportunities for accountants should those

services be liberalised and privatised. The five year plan adopted by IFAC in 1982

recognised the importance of governmental accounting and sought to work with

others and contribute to research about accounting for government bodies.

The public sector reforms that occurred in New Zealand and elsewhere have been

documented extensively in the literature. New Zealand was recognised as an extreme

and rapid mover, and a leader in aspects of its financial management reforms such as

Chapter One: Introduction

6

the GAAP based consolidated reports required by the Public Finance Act 1989.

When FRS-37 was finally approved in 2001 with sector-neutral application, the

consolidated financial statements subsequently produced by the Crown were hailed

as a model for government accounting worldwide and the country’s leadership in

accounting was regarded with considerable pride. According to Hagen and van Zijl

(2002, p. 5) “New Zealand pioneered the transition of public sector entities to accrual

accounting and modern financial management practices”. While State governments

in Australia were already presenting consolidated accounts preceding the

New Zealand development consolidation there was not applied at commonwealth

level and FRS-37 was seen as the first standard to require fully consolidated financial

statements for the whole of government at the highest level.

Subsequently there were indications that New Zealand would be moving away from

sector-neutral GAAP. The motivation for this thesis therefore was to understand the

developments to do with FRS-37 and their relationship to the related areas of

consolidation accounting, standards-setting, government accounting, and public

sector financial management.

Outline of the Thesis

The next chapter of this thesis explains the research method adopted and chapter

three provides a literature review of accounting thought on consolidation accounting.

Chapters four to nine present archival materials drawn from the periods of time

under examination that are relevant to the consolidation accounting issue. The

specific structure of these chapters is explained in more detail in chapter two.

Chapter ten summarises the research and attempts to draw some conclusions about

the FRS-37 event while also noting research limitations and directions for future

research. The sector-neutral consolidation accounting development has been under

intense focus for some years, and now as the sector-neutral platform has come into

question it is of further international interest. New Zealand led the way with its

reformed reporting initiatives and this research is therefore significant in that it

identifies matters that are relevant to others in pursuing similar developments.

CHAPTER TWO:

RESEARCH METHOD

Chapter Two Introduction

With the passage of the Financial Reporting Act 1993, New Zealand adopted an

approach to government financial reporting that has since become known as sectorneutral. Approved sector-neutral financial reporting standards normally apply to both

the public (government) and private (business and non-profit organisation) sectors alike.

An anomaly in this sector-neutral stance was that central government was exempted

from the consolidation standard SSAP-8 shortly after the Public Finance Act 1989 had

introduced the requirement for Crown GAAP consolidated accounts, and the exemption

was not removed when the sector-neutral environment was brought into effect in 1993.

Eight years passed before the approval of the sector-neutral consolidation standard

FRS-37 in 2001. This thesis seeks to understand what went on during this period when

consolidation GAAP was unclear and does so through a structured presentation of the

material using an historical narrative methodology, which takes into, account the

complexity of events and the length of time during which they occurred.

For a good part of this period I was personally involved in the consolidation accounting

developments in various roles that gave me different perspectives as matters unfolded.

Throughout the 1980’s and early 1990’s I was immersed in the academic accounting

and professional accounting environments. By 1994 I had been lecturing for a number

of years on consolidation accounting at several tertiary education institutions, I had

been with KPMG for two years as technical director where my work included practical

issues related to consolidation, and in a consulting capacity I had prepared a report on

the consolidation of Crown entities for the Treasury. In 1995 I became Coordinator of

Accounting Policy Development for the Treasury and was specifically involved with

the development of consolidation accounting policy for two years. From 1997 until

2002 as a councillor of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of New Zealand

(Institute), formerly the New Zealand Society of Accountants (NZSA), I was involved

in reviewing and endorsing the profession’s standards issued by Council, and as a

member of the Institute’s National Public Sector Committee from 1999-2001 I was

Chapter Two: Research Method

8

involved in the development of standards. While in the above roles I contributed

numerous submissions on various accounting standards and legislation.

Over this time I was in part responsible for some of the developments that occurred. I

therefore bring with me a personal perspective on some of the issues and a recognition

of my changing perspectives. For this thesis in the interests of impartiality to allow new

insights to come through I wished to better understand the range of perspectives and

wider issues not necessarily known to me earlier and to that end to put aside as much as

possible my own involvement in events. Consequently the historical research method

applied was chosen because of its capability for accommodating the problems of

perspective, as well as its academic rigour for formally structuring and conducting

inquiry into past events in a scientifically intelligible manner.

The purpose of this chapter is to explain the historical narrative methodology applied

together with why it was chosen, and why it is appropriate. The chapter also identifies

the sources and validity of the evidential material, and how that material is referenced.

It closes with an outline of the structure of the remainder of the thesis given the

methodology.

An Historical Approach to Accounting Inquiry

A review of the literature on an historical approach to accounting inquiry indicates it is

an emerging methodology for a discipline highly relevant to modern society, although

focused on events in the past it is a methodology that is being increasingly applied to a

field full of questions unanswered by other methodologies. Within the historical

research vein there are two broad streams of inquiry: the more traditional approach that

attempts to present the facts in the most objective manner according to the historian’s

interpretation, and the more recent work which recognises the subjectivity inherent in

any portrayal of events and may either consciously adopt a particular theoretical

perspective or explicitly recognise the work’s predisposition to perspectives. Given my

acknowledged involvement in the research event, to the greatest extent possible I

wished to both use my experiences and yet not be constrained by my predispositions

therefore I needed to understand the historical research approaches available in order to

choose my preferred approach.

Chapter Two: Research Method

9

Among the claims for adopting an historical approach to research discussed by Parker

(1997, p. 112; citing Tosh, 1991; and Previts et al, 1990a; 1990b) are that it offers

indicators of precedents, previous experiences, and conditioning factors (economic,

political, social, and institutional) that might affect future actions and policies. Further,

it can reveal and render visible matters previously ignored, it can be used to build a

view of the past, it can also be used to challenge and overturn beliefs and traditions. Yet

Ricoeur (1988, p. 6) declared “we cannot ask, ‘what really happened?’ since that is

the most troubling of all questions that historiography raises for thought about

history” (cited by Fleischman et al, 1996, p. 71).

What is History?

“History can be construed as event, story, or way of knowing” (Standford, 1987, p. 1;

p. 25; cited by Fleischman et al, 1996, p. 57). Each of these terms has a specific

meaning to historians, pointing to an intense scholarly divide apparent in the literature.

Fleischman et al (1996) explain that to view history as an event construes history as

knowing about facts of the past, also implying that the event has occurred and is

finished. The implication that an objective knowledge of the past is possible is

characteristic of the traditional perspective in history. Traditional historical research,

according to Napier (1989, p. 237) is concerned with understanding the past for its own

sake - both for intellectual and for utilitarian reasons.

History as story puts the emphasis on the subjective interpretation of the historian which

taken to the extreme suggests history is “an imaginative representation rather than a

series of factual, objective events” (Fleischman et al, 1996, p. 58). Funnell (1998,

p. 145) notes Tyson’s (1993; 1995) objection that the enterprise of accounting history is

contaminated when verifiable historical fact is combined in the one accounting history

with “unsubstantiated speculation derived more from the premeditated, imaginative

conjuring of the writer”. He moderates that story need neither suggest narratives are

nothing more than “literary replications of what are otherwise unconnected, chaotic

enactments through time” nor need they be in the contrasting view “indisputably

unfabricated textual representations of real events with a discoverable, as opposed to

contrived, relationship between them” (Funnell, 1998, p. 145). Fleischman et al (1996,

p. 59) also review these various debates. They cite Habermas (1990, p. 27) on

contemporary ideology, practices and language tainting portrayals of the past, and how

Chapter Two: Research Method

10

any representation of facts is shaped by the historian’s “inextricable frame of reference

and so must reflect value judgements”. The issues of facticity and subjectivity reflect

“the inexorable linkage that exists between the past and the present” (Fleischman et al,

1996, p. 59).

With reference to Carr (1986), Funnell (1998, pp. 147-149) explains that whilst it would

be somewhat naive to perceive the written historical narrative as wholly dependent

upon previous verification and discovery in the sense that the narrative would be

determined for the historian as the story unfolded from the evidence, a realist or

objectivist view would argue nonetheless the narrative is something which exists

independent of the historian’s efforts to “write up the past”.

History as a way of knowing refers to the use of historical processes for learning or

understanding e.g. the critical theory movement in accounting uses a variety of history

based arguments and materials to analyse the rationales and ideologies underlying

accounting practices. Fleischman et al (1996, pp. 58-59) detail Standford’s (1987,

p. 27) illustration of the structure of historical activity to show how the unseen becomes

seen as historical evidence i.e. the evidence is constructed unseen in the historian’s

mind and becomes seen through their production of historical evidence such as an

article or book, this manifestation then has an unseen influence on the public mind that

becomes seen as historical actions. They observe that this identifies “the central

problem of history as a method of knowledge”, the problem being that “an objective

knowledge of the past can only be obtained through the subjective experience of the

scholar” (Fleischman et al, 1996, pp. 58-59).

Fleischman et al (1996), and Parker (1997) both refer to Standford (1987) and Barzun

and Graff (1985) to describe the requisite talents and qualities necessary of historians

being knowledge of the field and era, discernment, and fair-mindedness such that their

work displays the indispensable scholarly virtues as to constitute a history. Fleischman

et al (1996, p. 60) describe “good history” as research that has been well written, wellargued, and well-documented, noting “events and the relationships between them,

comprise the historical field” but that in itself does not equate to the past. They define

evidence as “past events that illustrate or explain other events”.

Chapter Two: Research Method

11

The Application of History in Accounting

Carnegie and Napier (1996, p. 7) describe a recent “explosion in the academic literature

of accounting history”, with schools such as traditionalist, antiquarian, post-modernist,

Foucauldian, critical historian, and Marxist now recognised. Napier (1989) traces back

applications of accounting history to the early 1900s nevertheless, from the work of

The American Accounting Association Committee on Accounting History (AAA,

1970) that defined accounting history as a type of evolutionary social technology

through to positivist applications and the thrusts into contextualising accounting: citing

Hoskin and Macve (1986; 1988), Loft (1986; 1988), Hopwood (1987), Merino and

Neimark (1982), Merino et al (1987). Previts et al (1990a, p. 2) assert that “narrative

history represents a legitimate academic effort to add to the body of knowledge the

elements of past human accomplishments in order to place contemporary issues in a

more complete perspective”. New accounting historians now apply historical

methodologies to produce critical interpretations of events, or other accounts of the past,

some question whether historical facts even exist. Most recently deconstructionist

historians emphasise the interpretational sensitivity of messages obtained from a body

of text (Funnell, 1998).

New Accounting History

The historical narrative seems to have become “one of the charged code words of the

current struggles over history” (Appleby et al, 1994, p. 231; cited in Funnell, 1998,

p. 143). Funnell (1998) describes the emergence of deconstructionist critical

historiography where concerns with the method of presentation or messages obtained

from a body of text cast doubt on “the neutrality of the traditional writing technologies

available to new accounting historians” (Funnell, 1998, p. 142). He explains “the

naturalness and apparent neutrality of the narrative as a technique for writing

accounting history have given it a place which has allowed it to escape close scrutiny

for the most part” (Funnell, 1998, p. 144). Historical narrative has now attracted

attention “as an interested technique used in perpetuating and promoting long standing

social beliefs and structures which have been hidden in unobtrusive discourses (Funnell,

1996; Hopper and Armstrong, 1991, p. 405)” (Funnell, 1998, p. 144). Carnegie and

Napier (1996, p. 16) note too the propensity for new accounting historians to focus on

the structure and uses of accounting information “for control and even coercion, rather

Chapter Two: Research Method

12

than as a mere input into a rational decision-making process. Accounting is seen as a

method of making visible, and therefore governable, individuals, groups and

organizations”.

The combative style of recent literary expressions of new accounting history is

demonstrated by Sy and Tinker (2005, p. 63):

Historians have complacently paraded interesting data and evidence without

consideration of its validity or relevance. Philosophical concerns have been

methodically barred from consideration. Despite the Kuhnian Revolution, archival

antiquarianism reigns supreme. ...Kuhn’s critique [is used] to show archivalist

empiricism as incapable of proving a paradigm’s truth, and revealing how easily the

latter may succumb to popularist euphoria and ideologies.

The authors set out to sketch a “panorama in terms of a Non-Eurocentric, social,

gendered, environmental, public interest and labour orientation” (Sy and Tinker, 2005,

p. 47) latching on to most of the emergent themes now reaching publication. Consistent

with Funnell (1998) they assert that “developments in History Proper have by-passed

accounting history”. The use of capital letters indicates the dichotomy prevalent in the

wider discipline of history of upper case and lower case differentiation between old and

post-modernism ideas about history (Tosh, 1999; Jenkins, 1998; Iggers, 1997;

Hobsbawm, 1997).

New accounting historians have continued to use the traditional narrative form but “as a

means with which to question the accepted stories of accounting history and to

challenge...traditional accounting history” (Funnell, 1998, p. 144) - he calls these

counternarratives since they are “narratives none the less” (Funnell, 1998, p. 145).

Complementary Aspects of Traditional and New Historical Approaches

Carnegie and Napier (1996, p. 8) note the strongly worded depictions of a traditionalist

who decontextualises accounting and denigrates the past from the pomposity of the

present, and the new accounting historian “whose history is written through the

verbiage of obscure theorization, who eschews evidence for speculation, who ‘writes to

a paradigm’ (Fleischman and Tyson, 1995)”. Carnegie and Napier (1996) using Merino

and Mayper’s (1993) terminology referring to “aggrandisations of caricature” that can

be bridged:

Chapter Two: Research Method

13

We recognise that, in their substantive work, rather than in their polemics, the

differences between the various ‘schools’ are often more of degree than kind.

Mutual reliance (often unacknowledged) between the traditional and new historians

of accounting may be seen in the propensity of new historians to rely heavily on the

archival discoveries of the traditionalists, who themselves often find their work

enriched by an awareness of the conceptual debates of the new historians. (Carnegie

and Napier, 1996, p. 8).

Napier (1989, pp. 239-250) earlier recognised that archival research involving the study

of original accounting sources and documents in the discovery stage is an essential

precursor to interpretational research, pointing to the relevance of research both in and

outside of the ascendant paradigm. Fleischman et al (1996, pp. 63-70) argue that the

contribution of archival researchers is just as important as that of the persuasive

historians who write “without recourse to primary source material”. They cite Standford

(1987, pp. 111-112) who explains how scholars may construct their histories in a

variety of ways, giving the example of the narrative form whereby some entity is

identified then that single thread is followed over time to help the reader experience the

event.

Funnell (1996) advocates tolerance by the new accounting historians informed by

radical philosophies towards traditional conceptions of accounting history – noting the

new historians rely on traditionalists to generate much of the raw data for their

theorising. Funnell (1998) suggests it is the traditionalists emphasis on reliability of the

facts whereas the emphasis of new accounting historians is on interpretation, that shows

up their disagreement on subject matter and representational faithfulness. Fleischman et

al 1996, p. 62) conclude

the panorama of history is comprised of the multitude of approaches that exist along

the continuum. The scholar’s training, experience, belief system, and personal

preferences will direct him or her through the maze of alternatives.

The Explanatory Power of Accounting Historical Inquiry

Previts et al (1990a) distinguish between the narrative (story) and the interpretational

approaches to history but note that both approaches are capable of contributing to

knowledge on complex matters, each having advantages and limitations. Their paper

also notes some general limitations: a history may be incomplete for whatever reason

Chapter Two: Research Method

14

(official information restriction is noted as an example), the documentation of complex

events may require the introduction of assumptions regarding personal, institutional,

and/or environmental conditions that are unacceptably biased, the history may be

untruthful from a particular perspective, or the history may portray the subject

inaccurately.

Interpretational history may raise an expectation for explanation and causal analysis:

The historian searches for patterns of development and attempts to proceed from a

determination (what happened) to a contingency (how it happened) basis. Facts are

necessarily selected and organized through a judgmental process constrained by

time and are provisional according to the historian’s perception of the contextual

variables of the period studied.

History may not reveal the cause of an event as a certainty, but it can indicate

probable factors affecting the event. The historian’s assessment of the influence of

contextual factors rests not on possibility or probability alone but also on adjudged

plausibility. Indeed, the term cause is generally avoided when historical propositions

cannot be empirically confirmed or refuted. (Previts et al, 1990a, pp. 8-9)

Carnegie and Napier (1996, p. 7) caution against historical research attempting to

explain accounting in terms of economic rationales. They interpret the emphasis by

Previts et al (1990a; 1990b) on scientific inquiry and application of econometrics and

quantitative methods as inference of their advocacy of an inter-disciplinary approach to

accounting history research such that their characterisation of the interpretational

approach means one that emphasises explanation rather than economic theorising. They

note too that it is unlikely that any but the most insignificant historical problems are

amenable to a single understanding or explanation even using the criterion of

plausibility advanced by Previts et al (1990a, p. 9) “there are many plausible histories of

the same events” (Carnegie and Napier, 1996, p. 17).

In this vein Walker and Mack (1998, p. 72) challenge Whittred’s (1986; 1987; 1988)

findings of causal influences on consolidation accounting developments in Australia.

Whilst acknowledging lender influence they criticise undue reliance on secondary

sources of evidence, misinterpretation of the history of stock exchange listing rules, and

insufficient recognition of other possible influences:

It would be simplistic to suggest there was a one-way, causal relationship between

specific variables. Yet such a relationship is reflected in Whittred’s claims about the

Chapter Two: Research Method

15

history of the use of consolidated statements in Australian accounting practice:

lenders demanded the inclusion of clauses in contracts to ensure the provision of

consolidated data, which in turn led corporations to publish that form of

information.

It would be just as simplistic to suggest that there were causal relationships between

the contributions of accounting writers, regulation, and practice - even though this

sequence of events seems to provide a better explanation of the history.... (Walker

and Mack, 1998, p. 72).

The distinction made by Previts et al (1990a) between narrative and interpretational

history is further discussed by Carnegie and Napier (1996, p. 14) who suggest that

while a narrative may be little more than a chronology of events for documenting the

past: “narrative history may gain strength from the verve with which the facts are

communicated, the story is told. The literary style with which history is narrated helps

to lend credibility to the data and events uncovered by the historian”.

Parker (1997, pp. 139-140) considers that the discipline of writing is not only important

to historical research for linguistic and literary purposes - it also offers “the prospect of

revelation” in contrast to scientific research where writing up often commences only

after the research has concluded: a voyage of discovery awaiting the historian who

makes a start with but partial understanding of available evidence and its possibilities,

and through writing gains “new insights and understandings progressively as the

composition of the prose proceeds (Tosh, 1991)”.

The Historical Explanatory Narrative

Various authorities identified in the foregoing review have indicated validation of the

historical narrative approach notwithstanding other criticism in the literature. Funnell

(1998, p. 143) claims narrative is the “unavoidable, natural means of writing history and

the preferred vehicle for accounting histories” and that it is “of fundamental

importance...in the writing of both traditional and newer forms of accounting history”

(Funnell, 1998; citing Carnegie and Napier, 1996).

Goldstein (1976, pp. 140-141) states narrative has to do with the way in which

historians write up their research: “the superstructure of written histories”, Stone (1979,

p. 3) defines narrative to mean “the organisation of material in a chronologically

Chapter Two: Research Method

16

sequential order and focussing of the content into a single coherent story, albeit with

sub-plots” - cited in Funnell (1998, p. 147) who concludes that all narratives have:

...the common characteristics of a story, most notably a beginning, after which changes

occur which elicit reactions from the actors, and a conclusion as the actors attempt to

resolve problems (Dauenbauer, 1987, p. 165; Ricoeur, 1980, p. 174).

Funnell (1998, p. 143) recites Porter’s (1981) contention that the historical narrative

arises from the pattern and structure of life itself where events occur not just in

succession but with the order of events giving meaning to those which were previous

and those subsequent, and that for a written narrative to be regarded as a work of history

it cannot be an artificially construed rendition of life. A frequent citation in the literature

is Porter’s remark, cited in Poullaos (1994) and Funnell (1998, p. 145) among others,

that narrative provides:

the means to order the individual events which are proposed to constitute the facts

of history, thereby making them comprehensible by identifying the whole to which

they contribute. The ordering process operates by linking diverse happenings along

a temporal dimension and by identifying the effect one event has on another, and it

serves to cohere human actions and the events that affect human life into a

temporary gestalt. (Porter, 1981, p. 57).

Guthrie and Parker (1991, p. 5) concur with the emphasis given by Porter’s (1981)

method to conditions precedent, and with narrative offering the way to make sense of

historical events. Fleischman et al (1996, p. 62) describe construction of history as “the

metamorphosis of evidence into a coherent and probable picture”, being “clearly

individualistic” and requiring a thorough understanding of context Carnegie and Napier

(1996, p. 8) recommend “locating our narratives within an understanding of the specific

context in which the object of our research emerges and operates”:

We believe that accounting history is enhanced by locating our narratives within an

understanding of the specific context in which the object of our research emerges

and operates, that we all write, implicitly if not explicitly, to a paradigm. However,

the degree with which this needs to be emphasized depends on the particular subject

matter of our research. We also believe that historical research in accounting gains

its strength from its firm basis in the ‘archive’. (Carnegie and Napier, 1996, p. 8).

While Porter (1981) is not directed specifically at accounting, he is cited almost

universally in the literature reviewed above since he offers a conceptual framework and

theory based methodology for carrying out historical research. In accepting the merits

Chapter Two: Research Method

17

of the historical narrative, the preceding literature is mostly oriented towards the

validity of using historical approaches for accounting inquiry and with historiographical

differences. Poullaos (1994) offers an illustration of the adoption of Porter (1981) in the

accounting domain, and was responsible for inspiring the application of historical

methodology in this thesis.

Poullaos (1994)

Poullaos (1994) uses narrative explanation based on Porter (1981), combined with the

literature on the sociology of the professions, to explain the granting of the Royal

Charter to the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia in 1928 after forty years

of effort by proponents. He adopted an historical analysis approach to studying that

particular development in accountancy because of the archival basis of his evidential

material, and the specific nature of the event having involved two preceding failed

attempts and changing circumstances. Accordingly an historical narrative approach

“incorporating the results of a detailed sequential analysis of a number of related, but

unique, events” promised the most intelligible explanation, historical events being

shown by Porter to be particular, unique, and non-recurring such that looking for

general laws applicable to a class of historical events made no sense (Poullaos 1994, pp.

6-11, citing Porter 1981, p. 32). Poullaos identifies several issues in relation to his

choice of methodology:

Is traditional historical analysis of unique events still a valid form of scholarship?

What are its claims to scientificity, if any? How is it to be assessed? Is there a theory

of historical analysis and of the historical event which can provide an explicit and

defensible

methodological

framework

for

contemporary

historical

study?...Porter...purports to provide defensible answers to such questions. (Poullaos,

1994, p. 6).

Historical Explanation and the Sociology of the Professions

Much of the literature reviewed earlier talks about the contrasts between scholarship in

conventional history and in the social sciences. Poullaos (1994), as noted, provides an

example of the historical narrative approach integrated with the discipline of the

sociology of the professions. Fleischman et al (1996) discuss the distinction as follows:

It has been said that historians study the past, whilst social scientists use the past to

Chapter Two: Research Method

18

understand the present. Many historians today would reject this dichotomy and

ascribe to their own work critical contemporary importance. Nevertheless, the

distinction is useful. It remains generally true that historians examine particular facts

and inductively form conclusions if these facts present themselves in recurring

patterns. Social scientists, on the other hand, frequently adopt a nomothetic

approach in which they deductively seek out specific examples of events that

support a priori generalisations about human behaviour. (Fleischman et al 1996,

pp. 62-64).

They describe the dialogue between conventional and critical accounting historians as

tending to concern source materials and the above distinction between history and

social science, but that actually the margins of difference are blurred. They disagree

with the dichotomy of historians depicted in the literature as “one or other of those who

would impose upon the discipline a rigorous methodology characteristic of the social

sciences and those who would abdicate all rules of evidence in favour of a literary

exposition more typified by the humanities” (Fleischman et al 1996, p. 62) but rather,

they endorse the legitimacy of the range of methodological approaches for scholarly

application.

Funnell (1996) concurs with Carnegie and Napier (1996) too that historiographical

differences are more a matter of emphasis than of kind. He asserts that new accounting

history need not be synonymous with critical studies tied to prominent social theorists

such as Foucault and Habermas, and gives the example of Fleischman and Parker’s

(1996) collaboration with Kalbers to show how traditionalist accounting history may be

enriched by adopting pluralistic historiographies.

Poullaos (1994) remarks upon the controversy between the disciplines of history and

sociology as follows:

Some historians are concerned that sociological theories (1) do not allow space for

human agency (they are in that sense deterministic); and (2) do not allow for the

uniqueness of specific events (they tend to push events into rigid, predetermined

boxes or trajectories which gloss over the richness of history, i.e. the multiplicity of

factors which might otherwise be included in the historical field). (Poullaos, 1994,

pp. 24-26).

He observes the lack of attention in the sociological literature given to time and

temporal sequence whereas Porter’s theory focuses particularly on the temporal

relationship between events. Also that “sequential analysis of the historical materials

Chapter Two: Research Method

19

collected seemed to throw up anomalies for sociological theories” whereas Porter’s

theory “prompts a fine-grained approach...[urging]...a multi-level analysis and the

inclusion of any factor or element which leaves its mark on historical events whether

specified by sociological theory or not” (Poullaos, 1994, pp. 24-26).

Accordingly Poullaos (1994, pp. 24-26) places his emphasis on ensuring coherence of

the narrative rather than on coherence with sociological theory in his exposition of the

emergence of the event from its antecedent world. He notes none-the-less the

“significant sensitization role” played by sociological theory:

...it helped to structure the problem addressed by the...study; it helped in the

identification of focal elements for analysis; it was used as a source of normic

hypotheses. It also prompted adoption of a number of theoretical and

methodological positions.... (Poullaos, 1994, pp. 24-26).

The observations by Poullaos noted above seemed particularly apt to the consolidation

research issue at hand, especially his concerns over the multiplicity of factors, the

relevance of time and temporal sequence, the significance of perspectives at differing

levels of abstraction, and his focus on regulatory and institutional aspects of

accountancy. Given the similarities too in the geographical and institutional settings

Poullaos (1994) was thus taken as precedent authority for applying the historical

narrative methodology to my research issue. His demonstration of putting theory into

effect by using narrative to comprehend past events in accountancy was found to be

very helpful for subsequently interpreting and applying Porter (1981). Accordingly the

salient features of Poullaos (1994) where relevant to adopting Porter’s (1981) model are

included in the discussion that follows on explaining Porter and how his theory is

adopted for this thesis methodology.

Porter (1981): The Emergence of the Past

Porter (1981) presents a conceptual framework for historical explanation to attend to the

alleged disrepute of traditional historical narrative among researchers, claiming that

outmoded notions of positivism lay behind the typical perception of historical

explanation involving causal determinism which he contends “contradicts rather than

complements the practice of constructing narrative accounts of events” (Porter, 1981,

p. 19). While arguing that it makes no sense to look for general laws applicable to a

Chapter Two: Research Method

20

class of historical events given their non-recurring nature Porter contends the written

narrative has:

both a structure and a dynamic process that are common enough to be generalized and

abstracted for analysis, regardless of their specific content. The structure may be

described as a pattern of emergence from a set of indeterminate conditions, full of

possibility, to a realization of one concrete configuration, standing in contrast to what

might have been. The one concrete configuration, called the event, provides a kind of

focus in the middle of the structure, with the antecedent conditions ranged on one side,

and the consequences ranged on the other. (Porter, 1981, p. 20).

Porter (1981, p. 52) explains that the narrative account is unified neither by its

terminal event nor by some continuing subject but rather by the temporal structure

that emerges from potentiality to actuality. He shows that the construction of his

model requires the historical event to be carefully defined so that its contextual situation

is well understood - conceptualisation of the historical event is critical to establishing

the antecedent and subsequent periods, which are needed for discerning the contrasts

that reveal the significance of the event.

The historical event that is the subject of this thesis is the promulgation of the

consolidation accounting standard FRS-37. As noted in chapter one, with the passage of

the Public Finance Act 1989 the New Zealand government adopted business-style

accrual accounting in 1989 but an amendment to the existing consolidation accounting

standard SSAP-8 that required full consolidation accounting exempted the Crown from

its application. That exemption continued even after the move to a sector neutral

accounting environment and the establishment of the ASRB following passage of the

Financial Reporting Act 1993. The chronology of consolidation accounting

developments from the time the ASRB was established in 1993 until approval of

SSAP-8 eight years later in 2001 provides the raw data to be analysed by a process of

organising and structuring the dissertation in the way suggested by Porter’s model. His

systematic approach to the composition of explanatory narrative was adopted in order to

assimilate and interpret that material, and thus arrive at a form of explanation that could

claim to having scientific and academic rigour.

Plot Form

Porter proposes that selection of a plot form is important for identifying a consistent

Chapter Two: Research Method

21

frame of reference. This provides the research with a story-line, which he likens to a

hypothesis:

...half-formulated before the account is written, it guides the researcher in the

selection of data. It then provides a structure for his narrative, and it helps the

reader comprehend all the various details. It thus provides a foundation for the

process of reflection and anticipation...which gives the narrative its overall

coherence. (Porter, 1981, p. 48; pp. 151-158).

He offers 14 plot forms as examples for selection. One that he labels the “mode of

production” plot form is noted as useful for tracing an action plot in which institutions,

groups and individuals function as symbols of the transition to a new order. Given the

wider context of trade liberalisation and efforts to recreate world economic order from

the early 1970s this mode of production plot form is selected as the most appropriate for

application in this thesis given the objective of understanding the development of

sector-neutral consolidation accounting requirements bringing the public and private

sectors together.

The Duration of an Event and Durations Around an Event

Porter discusses the need for careful selection of the duration of the event because the

duration determines the level of abstraction appropriate for the research. Whereas an

event of short duration would require a detailed focus on the activities of individuals, an

event of longer duration would necessarily require a focus on groups or institutions,

rather than individuals, with the general rule being the longer the time frame the higher

the level of abstraction. This is due to Porter’s model involving contrasts over the

temporal duration of the event - which becomes a somewhat meaningless process if the

element being considered does not survive the duration.

Poullaos (1994, pp. 11-21) articulates Porter’s theory diagrammatically, depicting the

historical event on a two dimensional axis across space and time divided into four

durations. The event occupying a duration of internal development (E) otherwise

known as the plot or story-line is preceded by a period known as the antecedent world

(AW) made up of antecedent events (AE), and followed by a period of subsequent

world (SW) comprising subsequent events (SE). A fourth period represents the more

extended past preceding AW. The space on the vertical axis is occupied by sequences

Chapter Two: Research Method

22

of incidents within each duration contributing to the events E, AE, and SE. On the

temporal boundary between AW and E that vertical line represents E’s initial conditions

– importantly these are inherited from AW, and it is the potentialities inherent in those

conditions or elements, some of them mutually exclusive, which constrain E’s

development. While Poullaos’ diagrams present concise linear partitioning between the

periods related to an event, Porter deals extensively with the problems of defining those

boundaries. The configuration suggested to me by Porter’s model is more like that of a

light spectrum (or rainbow) where the transitions are smudged and multiple arrays may

appear together depending on one’s viewing position or perspective.

The significance of the boundaries between the durations is that their position

determines what is internal to the event’s duration and what lies outside (akin to the

accounting entity concept). Temporally contemporaneous incidents by definition

happen together and if related come within the range of the event itself so cannot at the

same time be external conditions or factors, or events subsequent. Sorting out these

configurations to be compared with the event is meaningful because they demonstrate

the existence of their relationships.

The definition of event which gives its duration and that of the antecedent world is

critical to Porter’s model. Identifying the duration of the event enables the researcher to

place what happened in context by comparing it with what came before and what

followed after. What happened during the event is regarded as internal transformation

and by default everything else is external. Porter advocates that this be done in a very

structured way such that the antecedent period is an equivalent period of time to the

duration of the event itself, so that the comparison of differences during transformation,

between periods, and with other events, is based on equivalent objects in terms of

intensity and levels of abstraction.

The duration of the event that is the subject of the research is eight years which

represents the whole period of development of FRS-37 from September 1993 when the

ASRB obtained legal mandate to approve sector-neutral accounting standards through

to October 2001 when FRS-37 was finally approved. Consistent with the duration of the

event the antecedent world is the approximately eight year period prior to 1993 which

takes the research focus back to 1985 - very early on in New Zealand’s radical new

public management-style (NPM) public sector reforms. A key feature of NPM

Chapter Two: Research Method

23

economics and the public sector reforms world-wide has been fragmentation of

governmental activities (for example the creation of the SOEs) which, in many cases,

has been a precursor to privatisation of those activities. Where those activities remain as

part of the government attention needs to be given to the issue of whether, and if so

how, their financial reports should be included or presented as part of the financial

reports for the government as a whole. Consolidation accounting provides one means of

addressing this issue.

Levels of Abstraction

Porter (1981, p. 60) takes the historical narrative beyond story-telling by requiring

the historian to adopt a consistent perspective through the plot form and to carefully

identify the event, which in turn provides guidance as to the most suitable level of

abstraction. The process of contrasting temporal changes in the elements of the

event, to discern what happened, requires the researcher to firstly “spatialize the

event’s form somewhat, so that it appears to be an object with a hierarchical

structure” (Porter, 1981, p. 130). The hierarchy is comprised of seven levels: a field

of zero abstraction (simply to ensure the historian can maintain the event took place

outside of his/her imagination), universals, forces (or factors or fields), concepts,

institutions, groups, and individuals. This system is explained further below together

with how it is applied to the research event in question.

Universals

Universals are higher order norms such as justice and progress and seem to provide

generally moralistic or rhetorical devices that help to motivate movement, change or

stability. Since they relate to longer historical eras they are not further considered for

this research question.

Forces

Porter identifies forces as consisting of the economic, political, technological,

religious, social (etc.) factors traditionally incorporated by historians into their

accounts (Porter, 1981, p. 94). In this thesis the forces considered to be important are

the economic and political forces of the time. The wider environment of trade

Chapter Two: Research Method

24

liberalisation, economic reforms, and harmonisation of regulation outlined in chapter

one give some indication of these forces: the perceived need for New Zealand to fit

within these forces was to some extent resisted until 1984 when, after the snap

election which resulted in a change of government, New Zealand embarked on a

radical set of economic and public sector reforms. As noted in chapter one,

accounting was integral to those reforms. Internationally, as those various economic

and public sector reforms have continued, New Zealand’s world leadership with the

public sector accounting aspects of its reforms has become well-known. The force of

world wide commitment to a global set of accounting standards has developed

especially strongly since the mid-1990s. Whereas all countries previously had some

leeway in their promulgation of accounting standards, the push to global standards,

culminating in 2002 with decisions in both New Zealand and Australia to adopt

international financial reporting standards devised for business organisations only,

has brought New Zealand’s sector neutral developments into question.

New Zealand’s political environment similarly acts as a force that is relevant to this

research. Its Westminster parliamentary system is distinctive for having a unicameral

rather than a bi-cameral legislature (Boston et al, 1996). Until 1993, the electoral

system was a simple first-past-the-post system dominated by two political parties:

Labour and National. This combination of the electoral system and the uni-cameral

legislature meant the party in power could and did dominate the legislative process

system allowing the party in government to dominate the legislative process which

thus meant that legislation could be developed and passed quickly and easily.

New Zealand’s economic and public sector reforms were not popular with the voting

public, which following a binding referendum conducted in 1992 and a further vote

in 1993, introduced a mixed member proportional (MMP) representational system

which has resulted in a coalition governments ever since.

Concepts

At the next level of the hierarchy concepts are taken to have two main meanings –

one being the presumed overarching missions pronounced by particular institutions,

groups, or individuals at the relevant point in time (for example the AuditorGeneral’s call for whole-of-government reporting was well articulated and well

known, although the sense of what it entailed seemed to change with the passage of

Chapter Two: Research Method

25

time, until it became a call for full consolidation accounting - representing

interpretation of GAAP).

Another meaning of concepts that emerged was in the sense of concepts that seemed

to go across institutions and also national borders, such as the term GAAP. One

dilemma that arose was whether concepts meant the same as institutions in some

situations in terms of their expression representing institutional views which might

have had the appearance of hidden agendas. Other important concepts noted that

pointed to underlying differences of perspective during the policy development

debates were accountability, transparency, credibility, independence, and regulation.

Institutions

Institutions are the organisations relevant to the research. The key institutions in

New Zealand that are relevant to this research are the OAG, the Treasury, and ICANZ

(formerly NZSA). The Auditor-General is a servant of parliament and performs a

constitutional role advising parliament on financial matters and auditing the

government’s handling of public money. The Treasury is an agent of the executive

government, that is the Treasury is a central government department and is responsible

for financial and fiscal management to the Minister of Finance. ICANZ is the sole

professional body for members of the accounting profession and is a non-governmental

organisation. Other institutions relevant to this research but less prominent include the

ASRB created as a Crown entity in July 1993 to give legislative status to financial

reporting standards, and the Crown Company Monitoring Advisory Unit (CCMAU)

also established in July 1993 to monitor performance of the Crown company portfolio

and to provide advice to the Responsible Minister on how to maximise benefits of

ownership (the other of the two Crown shareholding ministers being the Minister of

Finance, advised by Treasury). Overseas, institutions of interest include the Australian

and the international accounting standards-setting bodies and the International

Monetary Fund (IMF).

Groups

The interpretation of groups applied in this thesis is those parts within an institution that

have their own distinctive identity and may have different views or agendas. The groups

Chapter Two: Research Method

26

relevant to this research consist of several functioning within the Treasury and ICANZ.

Within the Treasury the key groups of interest are the Industries Group, the Financial

Management Support Service (FMSS) and the Debt Management Office (DMO).

Within ICANZ the key groups of interest are the Financial Reporting Standards Board

(FRSB) its predecessor, the Accounting Research and Standards Board (ARSB), and

the Public Sector Accounting Committee (PSAC).

The distinction between individuals, groups, and institutions can sometimes seem

blurred - particularly as issues evolve. Ryan (1999, pp. 577-578) found that public

sector accounting policy formulation occurred in policy communities within the

institutionalised relationships between governments, state bureaucracies and organised

interest groups, and also:

...the dynamics of policy communities change over time, as new issues arise and

political circumstances and personalities change. The dynamics between these

members of the policy community need to continue to be mapped to determine

whether this active partnership continues over time, or the power relationships are

challenged by emerging issues.

The policy communities inherent in the working groups etc for the purposes of this

thesis have been symbolised as one or other of the groups or institutions noted above

since for the analysis undertaken appropriate to the longer duration the levels of

abstraction selected are mostly at the higher levels being forces, concepts and

institutions.

Individuals

The duration of the event dictates the level of abstraction and therefore the decision

whether individuals should or should not be included among the research elements.

Porter explains that this is because individuals seldom last the full antecedent and

event durations and consequently the analysis process becomes meaningless. The

sixteen year duration of both the antecedent and research periods is such that the

research needs to be conducted at a group and institutional level rather than at the

level of individuals. Consequently the role of particular individuals is not considered

in this research, however it should be noted that the small size of New Zealand’s

policy community means that some individuals’ roles overlapped. Just one example

Chapter Two: Research Method

27

is Jeff Chapman who took an initial leadership role in the Treasury FMSS, served as

president of the NZSA at the time of development and enactment of the Public

Finance Act 1989, and served as Auditor-General in the early 1990s.

The actions of individuals is suitable for micro-studies of shorter duration and like

Universals to the other extreme are not applicable to this thesis.

Summary of Porter’s approach

Porter (1981, pp. 157-158) acknowledges that any explanatory narrative process is

inherently subjective but argues that application of his model enables historians to

provide narrative accounts that are keyed explicitly to a scheme of investigation

having general applicability. He argues that the desire for narrative unity need not

impose a structure on events that was not really there. It is the task of the historian to

show, by empirical evidence and responsible inference, what happened:

The narrative account is therefore comparable to and reflective of the actual past,

though it is never the same as the past. And because history is a public inquiry

(rather than private, as in fiction), the account can be judged and corrected by

other historians. (Porter, 1981, p. 53).

Poullaos (1994, pp. 19-20) summarised the historian’s task as: to analyse continuity and

change over the event’s duration, with the narrative providing for the reader an

“experience of the historical change”. This historical narrative might provide the reader

with an “understanding by following” of an historical event:

By the time the reader has completed the narrative, (s)he has followed a story which

details or evokes a sequence of actions and experiences of people where a

predicament is developed, then resolved. The emergence of predicaments over time;

of attempts to overcome them by choosing between situationally specific

alternatives; the subsequent emergence of consequences (intended and unintended);

creating in turn a further batch of predicaments: all these are common human

experiences. The strength of the narrative is that it taps into such experiences.

While Porter’s model provides the framework for analysis, the historical material and

sources from which it is drawn must also be explained and understood. The next section

addresses literature about historical evidence before explaining the sources from which

the evidence in this thesis is drawn.

Chapter Two: Research Method

28

Historical Evidence Sources and Validity

Historical evidence is described by Fleischman et al (1996, pp. 60-62) as only what has

survived the transition from past to present. They observe that evidence for accounting

history usually relies on written documents (although historians interpret document to

mean anything that can inform a scholar as to the questions) and that evidence in the

form of documents concerning events (or incidents) “does not equal ‘the facts’

[so]...evidentiary choices must be made from amongst the great mass of possibilities”,

but that historians of the mind-set that an objective knowledge of the past is real often

presume that facts speak unequivocally, are firm and knowable (citing Standford, 1987,

p. 79).

This can be compared with the perspective of history as events, where evidence is of

interest mainly for testing hypotheses, or story, whose proponents at the extreme would

argue that historical knowledge is impossible and merely literary discourse. Standford

(1987, p. 79) summarises the distinguishing characteristics of historical evidence in

terms of specialisation by time, place and subject of detailed factual knowledge that

acknowledges the uniqueness of an event, examined in sequence and context of the

events.

Documentary Archival Materials

Carnegie and Napier (1996, p. 26) note that public sector bodies often have a formal

approach to the preservation of records, thus the public sector is generally well served

as to the availability of primary research materials. Also the frequent need to justify

legislative provisions involving the accounting activities of public sector bodies and the

willingness of participants to defend their positions publicly mean that there tends to be

a range of official reports, discussion papers and other secondary material to draw upon

when researching governmental accounting developments.

The historical evidence for this thesis is mostly comprised of documentary archival

materials and participant observer notes and recollections. Written documentary

evidence tends to indicate what and how events happened. Evidence gathering for this

thesis relied heavily on scrutiny of published and unpublished written documentary

Chapter Two: Research Method

29

materials which were cross-referenced where possible. The documentary materials were

from a range of sources: some in the public domain, some subject to official

information clearance procedures, and some constituting private notes or recollections

from my personal involvement as a participant/observer. The materials in the public

domain consist of literature on consolidation accounting and public sector financial

management, public news releases, accounting promulgations, and government reports

and legislation. The materials not in the public domain include private papers collected

over a period of approximately 20 years such as correspondence, working papers,

submissions, and personal notes of meetings and activities. Other documentary

references include agendas, minutes, and materials made available to me in my roles

working with the Treasury and as a committee member and council member of ICANZ.

The thesis commenced while I was engaged in these roles and both the Treasury and

ICANZ facilitated access to information for this research.

Also certain records were made available on specific request, or were drawn from

unpublished Ministerial and Treasury archives accessed under the terms of the Official

Information Act 1982. The Treasury formally retained the right to review the content of

any material which was proposed to be published. This thesis has now been reviewed

and clearance has been granted. Treasury files are tabled separately at the end of the

references and are presented in date order because the date is the only consistent

reference point which allows a reader to check against the documentary sources. Their

unique reference labels consist of TR followed by the date of the document simplified

to six numbers.

The remaining documentary materials are referenced in alphabetical order. The

professional promulgations referred to in the thesis are organised under their issuing

body’s alphabetical listing and then organised either chronologically, alphabetically or

numerically depending on the nature of the reference. All of these references are readily

verifiable through publicly accessible library holdings. Legislation referred to

throughout the thesis is not formally referenced, in accordance with accepted protocol.

Participant Observation and Recollection

My personal involvement with the consolidation accounting developments occurred

between 1994 and 1997 whilst working with the Treasury, and between 1996 and 2002

Chapter Two: Research Method

30

whilst involved with ICANZ, as well as academic and professional involvement in

providing submissions on exposure drafts of standards in earlier times. Throughout

these times as a participant I kept my own dated notes of official meetings and

activities, as well as memories of auditory proceedings through attendance at meetings

and conferences. These notes assisted with my understanding of some of the materials

which at times is mentioned within the body of the thesis where they supplement and

clarify formal documentary records but they have not been formally cited or referenced.

Chapter Two Summary