Document

Primer on the CyberCrime Prevention Act of 2012

What is it?

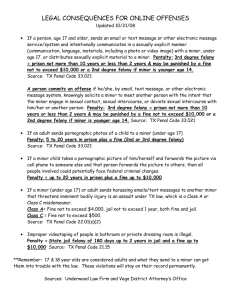

It is a penal law that concretizes the State’s compliance to certain international covenants against cybercrime and an attempt to be more responsive to the rapidly changing times ushered in by the developments in technology by regulating the widespread use of the internet in the commission of certain crimes as punished by the Revised Penal Code and other special laws. Worthy of note, the law provides more teeth – in its punitive aspect – to the State’s response to cyber pornography that mostly targets the youth demographic.

Specifically:

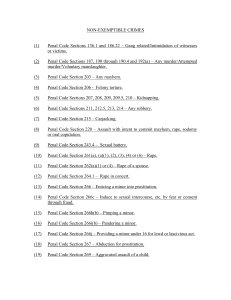

It punishes offenses against the confidentiality, integrity and availability of computer data and systems it likewise imposes penal sanctions on other computer related offenses like computer-related forgery, fraud and identity theft; it also looks into content-related offenses and makes punishable the acts of cybersex, child pornography, unsolicited commercial communications, amends the Revised Penal Code sanctions on LIBEL, and also punishes those who provide aid and/or abetting those engaged in the commission of cybercrimes.

It empowers the State, through various agencies of the executive department (i.e. the DOJ, the PNP, and the NBI) to ensure the swift detection, investigation, and prosecution of these punishable acts at both the domestic and international levels

Positive Aspects of the Law:

1.

It is the State’s compliance to the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime

2.

It attempts to be responsive to an emergent class of offenses which have not yet been defined as

“criminal offenses” under the Revised Penal Code or other special laws.

3.

Notably, it brandishes that it can now punish acts constituting “cybersex, cyber pornography” that almost always targets our youth

Negative Aspects of the Law

1.

this law still leaves much to be desired inasmuch as there are provisions contained therein that seriously infringe on the constitutionally guaranteed rights freedom of expression and speech, as well as the right to privacy.

2.

it provides blanket authority to the Executive Arm without any precautionary measures or sufficient safeguards in the manner by which the Executive shall implement the law.

3.

The eminent Contitutional expert Fr. Bernas, S.J. in his article on the Cybercrime and

Prevention Act of 2012 writes that no amount of IRRs (no matter how well-crafted they are)

could ever cure an imperfect law and this law, for one, smacks of several infirmities which will be pointed out below.

4.

A reading of Sec. 2 of RA 10175 sets forth noble purposes in the why this piece of legislation was enacted. However, looking at its last sentence, one truly cannot help but feel a sense of dread at how this law could be used or abused by the State. To wit:

“In this light, the State shall adopt sufficient powers to effectively prevent and combat such offenses by facilitating their detection, investigation, and prosecution at both the domestic and international levels , and by providing arrangements for fast and reliable international cooperation.” (emphasis and underscoring supplied.)

What is meant by “sufficient powers” in this context?

It is eerily similar to Presidential Decree 1877 and 1877-a during the Martial Law days when the government issued Preventive Detention Actions and/or Arrest

Search and Seizure Orders to those individuals who simply exercised their right to free speech and assembly.

5.

Sec. 7 of the Law is also a clear invitation to “double jeopardy” as it states:

“a prosecution under this Act shall be without prejudice to any liability for any violation of any provision of the Revised Penal Code, as amended or special laws.” (emaphasis and underscoring supplied.)

The provision appears to run contrary to constitutional guarantee that no shall shall punished twice for the same act, or what is otherwise known as the Double Jeopardy

Rule, inasmuch as the “liability” mentioned does not specifically exclude criminal liability.

6.

Sec. 6, in effect, changes the penal sanctions on libel and other related offenses punished in the Revised Penal Code as it indicates: all crimes defined and penalized by the Revised Penal Code, as amended, and special laws, if committed by, through and with the use of information and communications technologies shall be covered by the relevant provisions of this Act: Provided, That the penalty to be imposed shall be one (1) degree higher than that provided for by the Revised Penal Code , as amended, and special laws, as the case may be. (emphasis and underscoring supplied.)

7.

Most journalists aptly observe, if in other jurisdictions, the State has already decriminalized libel, why do we impose greater penalties in our country with this new law?

8.

As if adding salt to injury, law unduly empowers the Executive, thru the Department of Justice under Section 19 which reads: “When a computer data is prima facie found to be in violation of the provisions of this act, the DOJ shall issue an order to restrict or block access to such computer data.”

Yet the provision fails to show us what are the clear standards by which this order of restriction or blocking of access and leaves to up to the DOJ to unilaterally exercise her/his discretion on the matter.

In previous Supreme Court rulings, the sole justification for a limitation on the exercise of this right (free speech, et.al.), so fundamental to the maintenance of democratic institutions, is the danger, of a character both grave and imminent, of a serious evil to public safety, public morals, public health, or any other legitimate public interest. Let us seriously pray that this remains to the guiding force when the

DOJ acts pursuant to section 19.

Other observations: a.

That we supposedly have a present administration that prides itself on the “ matuwid na daan ” is by no means a guarantee to the ordinary citizen as these elected and appointed officials responsible for signing this law may long be forgotten by history, but the questionable provisions of this law will still remain, in all its punitive glory, unless and until the Supreme Court declares them as unconstitutional. b.

Besides, not all things that with begin with good intentions also translate into good results. I seem to recall the words of the late Justice William Douglas as reproduced in the Philippine Blooming Mill Case (81 SCRA 189):

The challenge to our liberties comes frequently not from those who consciously seek to destroy our system of government, but from men of goodwill-good men who allow their proper concerns to blind them to the fact that what they propose to accomplish involves an impairment of liberty.

… The Motives of these men are often commendable. What we must remember, however, is that preservation of liberties does not depend on motives. A suppression of liberty has the same effect whether the suppressor be a reformer or an outlaw. The only protection against misguided zeal is constant alertness of the infractions of the guarantees of liberty contained in our Constitution. Each surrender of liberty to the

demands of the moment makes easier another larger surrender.

The battle over the Bill of Rights is a never ending one. c.

That we do not have our Freedom of Information Law which supposedly “makes flesh” the People’s right to access to government information especially in those transactions and contracts involving public interest only compounds the problematic scenario that could inevitably arise with this new piece of legislation which penalizes those who may only be freely expressing their sentiments on the internet yet later on labeled as being “libelous statements.” d.

How far along would it be until this law covers those statements which are perceived as “unlawful utterances”, or “causing alarms and scandals”, or worse labeled as “treasonous” to the government?

Have we not learned from our own history? e.

This time around, with this law that contains several questionable and apparently constitutionally infirm provisions, who shall be the next target?

— the netizens? journalists? every Juan and Maria who has access to the internet? f.

paraphrasing the infamous words of IBP President Emeritus J.B.L. Reyes in the landmark case of Ilagan v. Enrile G.R. No. 70748, October 21 1985:

This law appears to be a Damocles’ sword wielded by the State whose value is not that it falls but that it hangs, and it hangs over every one who may at the present time, ONLINE OR NOT, be engaged or not in the defense or support of anybody or any cause.

Updates:

As of today, October 8 2012, the 12

th