Reducing Repeat Teenage Conceptions: A

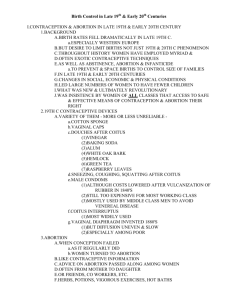

advertisement