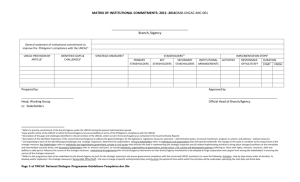

The Philippines - Office of the Ombudsman

advertisement