New Home Warranties for Canadian Consumers: Measures to

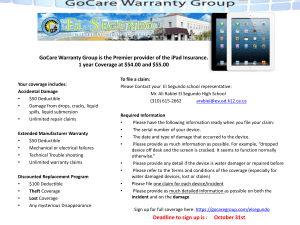

advertisement