KB0 Cover Pg Revised Oct 2005 - Institute for Global Labour and

advertisement

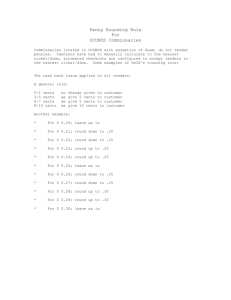

UPDATE as of October 10, 2005: Success at KB Manufacturing, Nicaragua The independent Edgar Roblero Union at KB has succeeded and is growing stronger. Sears responded correctly and in good faith, and factory conditions at KB are better than they were. Though there are still some smaller difficulties, which are being discussed by management and the union. The NLC will continue to monitor this case. There is no active campaign at this point. This is a significant victory. KB Manufacturing Granada, Nicaragua October 2003 A Report by the National Labor Committee th rd 540 West 48 Street, 3 Floor New York, NY 10036 212-242-3002 www.nlcnet.org KB Manufacturing Company S.A. Carretera a los Malacos Granada, Nicaragua Granada, a city of 120,000, is located about 30 miles from Managua. The KB plant is in what is known as a bonded area, which means it is a stand-alone factory, yet it is afforded all the financial incentives –100 percent exemption from corporate, municipal, and even sales taxes, and no import or export duties or tariffs—available in the Export Processing Zones. U.S. owned: Bayer Clothing in Pennsylvania (according to the workers, Bayer also has factories, at least, in the Dominican Republic and Mexico) Manager: Opened: January 1, 1998 General Manager: Vincent Morgan Battaglini General Administrator: Paul Hollingsworth Human Resource Hazel Herrera Phone: (505) 552 – 6573 Fax: (505) 552 – 5923 Number of workers: 354 / Half men and half women: (In 2001, there were 650 workers at the factory.) 317 on the production lines, including supervisors 16 in the warehouse 10 in maintenance 4 mechanics 7 in administration Production: KB Manufacturing specializes in making suits, especially jackets and blazers for men. There is also a very small production of pants. Labels: In June 2003, about 50 percent of the production was for J.C. Penney, with the other 50 percent for Sears. The J.C. Penney labels include Stafford, J Ferrar, and City Streets (WPC – 11935) and, beginning in September, Towncraft. These jackets retail for between $99.99 and $190. The Sears label is David Taylor (RN 15099). Blazers in black, gray, dark green and blue retail from $80 to $160. Another label is Austin Leeds Collection / Robert II (RN 56881). KB Manufacturing could have been a model factory. In November 2002, management reached an agreement with the Independent Workers Union Edgar Roblero, and apparently was interested in building a new, more positive relationship with the workers and their union representatives. Factory conditions seemed to improve. The CST – JBE federation asked the National Labor Committee / No More Sweatshops Coalition to include KB Manufacturing on any list of better-than-average factories in the developing world that we were working on. Then the bottom fell out. Just two months after signing the breakthrough agreement, KB management set out to attack and destroy the union, to which 78 percent of the workers belong. Out of the total workforce of 354, 35 are management staff and what are known as “confidence employees” who are by law ineligible to belong to the union. Of the 319 eligible workers, 250, or 78 percent, are members of the union. Eighty-five percent of the women workers in the factory are affiliated to the union. The company is again trying to set up a rival yellow union. We will return to this later. SUMMARY: ASSAULT ON LABOR RIGHTS 10-to-14-hour daily shifts. Workers may be at the factory up to 70 hours a week. Base wage of 22 cents an hour and just $10.54 a week. With attendance and production bonuses workers can earn 34 to 78 cents an hour. The average wage is approximately $4.00 a day, 50 cents an hour. Anatomy of exploitation: Corporate time motion study breaks the 150 operations necessary for sewing a J.C. Penney or Sears blazer into time frames of 1/100th of a second, while assigning piece rates as low as 6/100ths of a cent. On average, workers paid just $1.46 for each J.C. Penney and Sears blazer they sew. Blazers retail for $90 to $190. Wages range from just 8/10ths to one and 6/10ths of one percent of the retail price. Constant relentless pressure to produce: Some women must sew one piece every 5.76 seconds; 10.42 pieces per minute; 625 pieces per hour; and 6,000 pieces per day to earn a production bonus of $3.87 a day. th Workers shortchanged on their legal 7 Day’s pay. Over the last 2 years, the workers have lost the equivalent of three months’ wages. Constant threats to move the work to China: Company official tells the workers “listen, behind every Nicaraguan working here there are over 1,000 Chinese who want jobs – and they are more productive.” Pregnancy tests mandatory for all new female employees. Harassment of pregnant women, who are switched to new operations against their will, which increases the pressure on them and lowers their wages. Extreme heat: Factory temperatures reach 105.8 degrees – workers dripping with sweat. Lint and dust fills factory air / excessive noise levels / inadequate lighting. Codes of conduct only appear when J.C. Penney or Sears representatives visit the factory. KB management launches systematic campaign to destroy the Independent Workers Union, which –despite the repression—has the support of over 78 percent of the workers. General Manager Battaglini threatens that any workers who join the union will be fired and that “if the union stays, the company will close.” Promotions and higher pay goes only to those who publicly quit the union. Management sets up a yellow, or company union. This is a hugely important watershed case. If a union as strong as the KB union can be destroyed, it will clear the way to wipe out the few remaining maquila unions and roll back labor rights standards across all of Central America and the Caribbean. It will assure that workers will have no voice in the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas. HOURS 14 hour shifts / At the factory 70 hours a week The regular shift at KB is just shy of 10.5 hours, from 7:00 a.m. to 5:25 p.m., Monday through Friday. The workers receive two breaks during the day, one 20-minute break in the morning, and 40 minutes for lunch. Actual working hours each day are 9.6 hours, which comes to a regular 48-hour workweek, which is the legal limit in Nicaragua. However, in July 2003, the sewing operators were working until 9:00 p.m. every night. This puts them at the factory 14 hours a day, 70 hours a week. WAGES A base wage of 22 cents an hour, $2.11 a day, $10.56 a week. With attendance, overtime, and production bonuses the workers can earn between 34 and 71 cents an hour. The base wage at KB is 31.60 cordobas per day, or $2.11. For the 9.6 hour daily shift this comes to 22 cents per hour, and $10.56 for a 48-hour week. Base Wage 22 cents an hour $2.11 a day (9.6 hours) $10.56 a week (48 hours) However, if a worker has perfect attendance and punctuality for the week, she will earn what is known in Latin America as the seventh day’s pay – or attendance bonus. In effect, she will be paid the base wage for all seven days, including Saturday and Sunday. This will bring her weekly earnings up to $14.88, and 31 cents an hour. Base wage plus the attendance bonus 31 cents an hour $2.98 a day (9.6 hours) $14.88 a week Production bonuses, or incentives, are more and more common across Central America. Management arbitrarily sets very high daily and weekly production goals. At KB, if you make the goal, you receive a production bonus of 58 cordobas a day, or $3.87. Management tells the workers, the harder and faster you work, the more you produce, the more you will earn. This brings the top sewing operator’s wage in the factory to 71 cents an hour. In actuality, sewing operators’ wages at KB range between 34 and 71 cents an hour, averaging 50 cents an hour. Wage range including attendance and production bonuses 34 to 71 cents an hour $3.26 to $6.82 a day (9.6 hours) $16.32 to $34.08 a week (48 hours) $70.72 to $147.68 a month The workers point out that they are frequently paid less than the legal overtime rate, which should be paid at a 100 percent premium, or as double time. Some workers say they are paid as little as four and five cordobas an hour for overtime work, which is just 27 to 33 cents an hour, and is definitely short of the legal limit, which at the low end would be at least 44 cents an hour. The following two pay stubs from July 2003 would be typical for the factory. The first shows an operator working a 48-hour week, and earning 245.93 cordobas, or $16.41, after deducting for the INSS Social Security Health Care System. This comes to 34 cents an hour. If further deductions for food and medicine were taken out, this woman took home just $12.54 for the week. This second pay stub shows the operator working 7.58 hours of overtime for a total workweek of 55.58 hours. After deducting for Social Security healthcare this woman earned 509.67 cordobas, or $34.00, which would come to 62 cents an hour. For the last 2 years, the KB factory has been illegally underpaying its workers each week by miscalculating their 7th Day attendance bonus. Nicaraguan law (Labor Code article 84) is very clear that the 7th Day’s pay should be calculated on the basis of the average wage the worker earned during the week “including the base wage, incentives and commissions.” KB management failed to do this, and instead paid the 7th Day’s pay just at the base rate of 34.08 cordobas, or $2.27. This was illegal since the average daily wage at the factory is approximately 60 cordobas, $4.00 a day, or 50 cents an hour. So for the last 2 years, KB has been shortchanging the workers of $1.73 a week in wages legally due them. Again, this might not seem like a lot to us, but when you are earning just 50 cents an hour—and racing to earn your production incentive—this is nearly 3 hours in lost wages each week. For the 2 year period, each worker lost approximately $233.56, which amounts to the loss of up to three months’ wages. Overall, the 319 workers in the factory lost upwards of $74,500 during this period. This is no small loss for workers already trapped in abject poverty. But the union won a major victory here. As KB’s general manager Battaglini was refusing to meet with the union, the union’s executive board simply paid a surprise visit to his office on th August 13. When they challenged him on the miscalculation of the 7 Day’s pay, Battaglini asked for one week to investigate the issue. At the end of the week, the workers finally started to receive their proper 7th Day’s pay. This was a real victory for the union, and it was another concrete demonstration of why it is so critical that the workers have a voice. This is why KB management hates the union so much. The union is too effective in pressuring KB to respect Nicaraguan labor law. P RODUCING THE JACKETS / THE ANATOMY AND SCIENCE OF EXPLOITATION The fabric is cut in the United States, and the assembly is done in Nicaragua. There are 13 production lines in the KB Factory, ranging from 20 to 45 workers per line. The median number of operators per line would be 23 to 24. No one assembly line produces an entire jacket, rather this is the combined work of all the lines. Each line, however, specializes in particular operations. Line #1, with 45 operators, is known as the “front area,” where the front of the jacket is worked on. Line #2 works on the jacket lining. Lines # 3 - #5 and #6 are involved in various assembly operations. Line #4 produces the sleeves and sews buttons. Line, or area #7 inspects the completed garments, and so on. The workers explain that, on average, the sewing of each jacket requires 150 operations. There are slight variations from jacket style to jacket style, for example, requiring fewer or more buttons on the sleeves, but in the end the average for each jacket remains 150 operations. Everything in the factory is done according to a piece rate system. You get paid according to how many pieces you complete. The U.S. Bayer Clothing Company creates an engineering –or time motion – study which lists the over 360 possible operations involved in making any style jacket. It then assigns a time frame to each specific operation, in other words, how long the worker is given to finish each piece. Each operation is then assigned a specific piece rate, or what the worker will earn per operation. One might imagine that the Bayer Company would break each operation into time frames of minutes. It does not. Each operation is broken down into time frames of 1/100th of a second! This is the anatomy and science of exploitation. The time frames range widely from just 5.76 seconds allowed per operation, for a piece rate of . 0006466 cents, to nine minutes and 43.2 seconds per operation, with a piece rate of six and a half cents. The first example above was listed as operation #2035, described as “FUS TAPA 1ZQ Y DER” (fuse left & right tape). The time frame allocated – or SAMS (Standard Allotted Minutes) – was .0960 and the piece rate, in cordobas, is .0097. To arrive at the dollar value here, just divide the cordoba figure by the current exchange rate of 14.99 cordobas to the dollar (.0097 ÷ 14.99 = $.000647). The woman sewing this operation would have to complete: One piece every 5.76 seconds; 10.42 pieces per minute; 625 pieces per hour; and 6,000 pieces per day! If she was lucky enough to reach her goal she would earn a production incentive of $3.87 for the 9.6 hour shift. The second example listed above is noted as operation #2281, described as “Coser BCMGA a mano,” (sew BCMGA by hand) for which the worker is allowed 9.72 SAMS, or 9 minutes and 43.2 seconds, and is paid .9801 cordobas, or 06.534 cents per piece. This sewer would have to complete: One piece every 9 minutes and 43.2 seconds; 6.17 pieces per hour; and 59.232 pieces per day. If she reached this goal, she would also earn the $3.87 production incentive for the 9.6-hour daily shift. A more typical time frame would be operation # 0310, described as “pegar cuello” (attach collar), in which a sewer would have to complete: One operation every 66.24 seconds; 54.35 operations per hour; and 521.74 operations per day Her piece rate would be .00742 cents per completed operation. Operation # 0080, “pegar bolsillo/ciso” (sewing plain pocket), is given a time frame of completing: One operation every 2 minutes and 27.6 seconds; 24.39 pieces per hour; and 234.15 pieces per day. Her piece rate would be .01653 per operation. With 100 percent efficiency for the 9.6 hour shift she would also earn the $3.87 production bonus. So if a sewer operated with 100 percent efficiency, reaching her daily production goal, she could earn a top wage of 71 cents an hour –22 cents an hour base wage plus a 9-cent-an-hour attendance/productivity bonus, and a 40-cent-an-hour production bonus. However, most workers cannot reach the excessively high production goals management sets. The actual average hourly wages in the factory hovers around the 50-cent range. The time frames the U.S. company allocates, broken into 1/100ths of a second, create a relentless constant pressure to race through each operation in order to reach your production goal. The clock is constantly ticking. The workers say they face constant pressure and threats from the supervisors and managers. If they fall behind their goal, they are scolded. If this happens more than once, the threat is that they will be taken to the human resource office where a warning or complaint will be written up and entered into their files. Enough of these complaints—three or four of them on your record—and you can be fired for not working fast enough, without receiving even one cent of the back severance pay owed you. Squeezing for Pennies The KB company is constantly trying to cut costs and squeeze more out of its workers. So in August, general manager Battaglini walked the shop floor holding 20 cordoba ($1.33) bills in his hand. He walked around approaching the poorest workers and the fastest workers telling them, “Look. I’ll give you these 20s if you can speed up your operation.” Needing the money, the workers would race to exceed their goal. After each little successful demonstration, Battaglini would yell, “You see, everyone can work faster, and we need to increase the production goals now that we’ve demonstrated how easy it is to fulfill them.” To put this into practice, Battaglini tried to cut the piece rate to sew pockets by 43 percent. Currently, a team of two workers must sew two pockets on 1,000 jackets a day—10,000 pockets on 5,000 jackets a week. The piece rate is 0.2631 cordobas, or 1.755 cents, for sewing the two pockets. The piece rate for each pocket would be 0.88 cents. Since each worker is required to sew 1,000 pockets in an eight-hour shift, this would come to completing 125 pockets an hour, or one every 28.8 seconds. Since this is impossible, the workers are working 1.6 hours of overtime a day, for a 9.6-hour shift. It is very rare, but if this team of two workers could reach their production goal every day, together they would earn $17.55 a day, or $8.78 each. We know from a wide review of August paystubs that this is an unheard of wage. The very highest sewer’s wage we found was $37.56 for the week, and approximately 78 cents an hour. The vast majority of the pay checks ranged between 300 and 450 cordobas, or $20.00 and $30, which would comes to between 42 and 63 cents an hour. The workers own best estimate puts the average wage at 50 cents an hour—including base wage, attendance and production bonuses, and overtime. Battaglini tried to lower the piece rate for sewing pockets to 0.150 cordobas—1 U.S. cent—for each two pockets completed. This would bring the piece rate per pocket down to half a cent. If Battaglini could push this through, the result would be a 43 percent cut in the existing piece rate, which would have a huge negative impact on the workers’ wages. Instead of theoretically having the possibility of earning $8.78 a day if they made their quota (though in reality the workers earn only a portion of this), the new rate would mean they could only earn $5.00 at most. However, once again the union successfully fought to defend the workers and under pressure the general manager had to sign the following agreement, dated August 18, 2003: “We, Vincent Battaglini, Angel Avalos, Abelardo Diaz and Jeanette Perez, the last two being operators working in the front cover area, at a meeting with management agree: That Mr. Vincent Battaglini will maintain the piece rate for sewing pockets at 0.2631 cordobas [$0.1755], with the condition that both Mr. Abelardo and Mrs. Jeanette commit to produce no less than 1,000 pieces a day between them and 5,000 pieces a week, when there are two pockets. Signed: Vincent Battaglini, General Manager; Angel Avalos, General Secretary, Edgar Roblero Union; Jeanette Perez #784 and Abelardo Diaz Martinez #1032. If there were not such a strong union, nothing would stand in the way of management’s constant race to the bottom, slashing piece rates to just a half cent per operation. This is another reason management wants to destroy the independent union. Workers paid a range of 71 cents to $2.07 for every jacket they sew—an average of $1.46 per jacket. Wages amount to as little as 4/10ths of one percent of the retail price. If a worker reaches his or her production goal, we know that they will receive a bonus of $3.87 for the 9.6-hour shift. This is on top of their base wage of 22 cents an hour, and their attendance — or 7th day—bonus of another 9 cents. This would bring their total hourly wage to .71 cents. Few workers operate with such 100 percent efficiency levels, and actual average wages hover in the 50 cent range. However, even if we take the very highest wage, which few workers earn, then the total daily payroll for all 304 sewing operators comes to $2072.06 ($0.71 x 304 = $215.84; $215.84 x 9.6 = $2,072.06). These 304 operators must complete 1,000 blazers or jackets per day. This means that at the very highest end, the direct labor cost to sew each jacket would total $2.07 (2072.06/1000 = $2.07). As the Sears’ David Taylor Blazers range in price from $80 to $160, the direct labor cost at the high end is between 1.3 percent and 2.6 percent of the jacket’s retail price. Now, if the workers did not receive their attendance bonus and were unable to reach their production goal, they would lose all or part of their production incentive, and at the low end their wages would fall back to the factory’s base rate of just 22 cents an hour, or $2.11 for the 9.6 hour shift. Suppose they were able to sew just 900 blazers, falling 100 short of their mandatory goal. The 304 operators would now earn 22 cents an hour, and their total daily payroll would be just $641.44 (304 x $2.11 = $641.44). The direct labor cost to sew each jacket would fall to only 71 cents ($641.44 ÷ 900 = $0.7127). In this case, the workers’ wages would amount to just 4/10ths of one percent (.71 ÷160 = .00444) of the blazer’s retail price. On average, the workers are paid $1.46 for each jacket they sew. ($0.50 average hourly wage x 9.6 hours = $4.80; $4.80 x 304 hours = $1.459.20; $1,459.20 x 1,000 blazers = $1.4592.) For Sears and J.C. Penney blazers retailing for $90 to $190, this means that the worker’ wages amount to only 8/10ths of one percent to 1.6 percent of the jacket’s retail price. ($1.46 ÷ $190 = 0.00768; $1.46 ÷ $90 = 0.01622). In the anatomy of exploitation, the real wages are driven ever lower. If the workers are able to consistently reach their quotas, management responds by simply raising the goal. The workers have no voice in any of this. P OOR WORKING CONDITIONS: Mandatory pregnancy tests: All new female employees are required to present a urine analysis. If the test is positive for pregnancy, the woman will be immediately terminated. Maltreatment of pregnant women: Pregnant women are routinely switched from the operation they are familiar with to a new one. Management claims it is moving the women to “softer operations.” But none of the women want this, since the stress and tension of learning new operations only makes things worse, and as their production drops, so do their wages. The women say this is a management strategy to harass them in hopes they will quit. If successful, this will send a clear message to all the women in the factory not to get pregnant. Also, when pregnant women are given permission to attend an appointment at the Social Security health clinic, the day is discounted from their vacation time. Extreme Heat: Factory temperature can soar to over 100 degrees. Workers have actually recorded temperatures of 105.8 Fahrenheit. The workers describe themselves as constantly dripping with sweat. The excessive heat, especially combined with the high humidity, exhausts everyone. Inadequate toilet facilities: At the KB factory there are just four toilets for the women and two for the men, while according to Nicaraguan law there must be at least one toilet for every 15 women and one toilet for every 25 male workers. Poor lighting: There is insufficient light to work by, especially in the sewing area. According to Ministry of Labor measurements, the illumination is less than one half of what would be acceptable. The workers say that the concentration on minute details under such poor lighting causes constant strain, headaches, and blurred vision. Such poor lighting conditions can also lead to work accidents. Excessive Noise Levels: In several areas, but especially in the final assembly department, the Ministry of Labor recorded excessive noise levels reaching 96.3 decibels. Under US OSHA standards, workers should not be exposed to such noise levels for more than 35 minutes. Given that the sewers are working at least a nine-hour shift, they are being exposed to noise levels well in excess of 1000 percent of what is allowable in U.S. standards. Medicines mismanaged: There is a small clinic at the factory. But the staffperson appointed by the human resource manager to run the clinic is not a nurse. Moreover, management has assigned workers to handle the emergency first aid kits which are on the shop floor. These workers, who have received absolutely no training, are sometimes distributing prescription medicines such as enalapril— which is used to treat hypertension—to other workers who are suffering from stress from racing to meet the excessive production goals in suffocating temperatures. The union wants much better controls here. Factory air filled with lint dust: There are insufficient dust extractors, causing the air to fill with dust or lint particles from the cut cloth, which the workers must breathe in. Cafeteria is too small and located dangerously close to the huge factory boiler: The cafeteria is too small and located right beside the huge boiler which throws off tremendous heat. Even more important, the cafeteria food is not safe. In August alone, more than 40 workers suffered food poisoning from the poor quality food and unsanitary conditions. Also, the workers report that the company has started – perhaps to cut costs – to mix the factory’s drinking water with well water, which now gives the water a foul and salty taste. Forced overtime / shortchanged on overtime wages: In May 2003, the workers were forced to work overtime every Saturday from 7:00 a.m. to 5:25 p.m., but were illegally paid the same hourly wage they receive for regular time. Those who cannot stay for overtime – no matter how serious the circumstances – are banned, as punishment, from all future overtime work. Of course, given the low wages, the workers depend on overtime to survive. Cleaning fluids irritate operators: Some sewing operators working next to the cleaning section complain of being affected by vapors from “rust out,” “block out,” and neutralizer #7, which are used to clean the jackets. In areas where the workers handle toxic chemicals, such as in maintenance of the boiler, the Ministry of Labor recommends that these workers receive lung and liver tests. National holidays arbitrarily altered: The workers complain that KB management arbitrarily switches national holidays, so, for example, the factory is open on May 1, and as a substitute the workers are given off April 14. But as the workers point out, if you are required to work on a national holiday you must be paid double time, whereas they receive just straight time for April 14 day off. (Nicaragua has nine national holidays: January 1, Holy Thursday and Good Friday, May 1, July 19, September 14 and 15, December 8 and December 25.) More recently, the Independence Day holiday on September 14 and 15 fell on a Sunday and Monday, meaning the workers had the right to Tuesday, September 16 off. But management has such enormous discretionary power that it was able to pressure many of the poorest workers into coming to work that Tuesday, which was a legal day off. Human resource chief Herrera went through the factory the week before telling the workers, “Remember that we all have needs. The company needs you and you need us, and, of course, remember the loans.” So about 80 workers who either had small loans out or needed some money due to an emergency were forced to give up their day off and go to work that Tuesday. Constant pressure to reach excessive production goals: Due to the relentless pressure to meet excessive production demands, the workers explain that –in practice—they are not free to drink adequate water, especially given the extreme heat, or to use the bathrooms. The workers describe this as not only humiliating, but also affecting their health. Codes of Conduct disappear after audits: Sears’ code of conduct is posted only when Sears’ representatives visit the factory. After they leave, the code comes down. As of July 2003, there have been no audits this year, so the codes have not been posted at all. Threats to take the work to China: Thomas Iacoca, who routinely travels from Bayer’s office in Pennsylvania to monitor production in the KB plant, tells the workers, again and again, that they must improve their productivity—if not , the factory will be closed. “Listen,” he says, “behind every Nicaraguan working here there are over 1,000 Chinese who want a job—and they are more productive.” The race to the bottom in the global economy has now even reached Nicaragua, one of the poorest countries in Latin America, where over 50 percent of the people are forced to eke out an existence below the poverty line. The base wage in Nicaragua, which is 22 to 31 cents an hour, is now too high. Assembly workers in Nicaragua are now to be pitted against workers in China in a race to the bottom. THE LOST CHANCE How KB Manufacturing went from being nearly a model factory to systematically attacking and violating the rights of its workers. KB Manufacturing’s record on respect for worker rights has not been a good one. The first independent union at KB was formed on March 3, 2001. Just a month later, management began illegally firing all 48 newly elected union leaders and founding members. The firings were directed by the then General Manager, Herman Vogel Leal, who has since been replaced by Vincent Morgan Battaglini. Simultaneously with the firings, management began quickly setting up a yellow, or company, union. A year later, on April 11, 2002, management “signed” a collective contract with the yellow union they had erected. The workers, on the other hand, despite all the firings and repression, wanted no part of this sham. They reorganized their real union, which by October 2002 was strong enough to simply take over the yellow union, replacing its company-picked “leaders” with an independent union slate elected by the workers. The “Edgar Roblero” Independent Workers Union was now legally recognized and could turn its attention to improving the existing contract. At the outset, things went relatively smoothly. Serious negotiations took place between the union and KB management, leading to an agreement which was signed on November 5, 2002. The agreement was in many ways a breakthrough, demonstrating that management was interested in building a new and more positive relationship with its workers. The new agreements included: The company would set aside space for a union office – with electricity and a phone – inside the KB factory before January 1, 2003. Starting in November 2002, as a sign of good faith, the company would contribute to the union, “union dues” of five cordobas, or 33 cents, per union member per month. (We are not speaking a lot of money here. For the approximately 250 union members, the company would be contributing $82.50 a month.) First aid kits would be supplied with necessary basic medicines. A worker facing serious problems which cannot be resolved at the supervisor level has the right to meet directly with the general manager. On December 8, a religious festival for the Immaculate Conception would be observed in the factory, and a worker / management commission would be in charge of making the arrangements. On December 14 there would be a Christmas party at the factory for the workers’ children. Workers would no longer be punished for arriving just a few minutes late to work, which is often due to factors beyond their control, such as an old bus breaking down. A nurse will be hired to staff the factory clinic. From this point forward, there will be regularly scheduled monthly meetings between the union and management. Other contract clauses were also raised: Pregnant women returning from maternity leave should retain their old jobs and not be switched to a different position, which in effect lowers their wages as they struggle to learn and master a new sewing operation. The company would guarantee a clean and hygienic cafeteria and would subsidize 55 percent of food costs. A bipartite commission would be formed, made up of the union and management, to deal with conflicts in cases of firings. Management must first discuss firing with the union. If a joint decision cannot be reached within 72 hours, then the case should go to the Ministry of Labor. The company will provide a certain number of scholarships / worker training courses for the workers to increase their skills. A “salary commission” would be formed of management and labor to annually examine and discuss a modest wage increase beyond the minimum wage increases decreed by the government. Frank and productive discussions were going forward on many fronts, and it was at this point that the CST-JBE Federation – to which the Independent Workers Union Edgar Roblero belongs – asked that the KB Manufacturing plant be included in any list that may be drawn up of better than average factories in the developing world. The goal here was to recognize and celebrate factories that were trying to do the right thing. They might not be perfect, but they were moving in the right direction, and these factories were certainly far better than average. They deserved to be recognized or highlighted, and to receive more work. Unfortunately, starting in January 2003, the bottom fell out on management’s new more positive relationship with its workers and their union. KB management went on the attack. The workers say that General Manager Vincent Battaglini is directing an aggressive campaign to try to isolate and destroy their union. One tactic is to spread fear. Battaglini is telling the workers that anyone who joins the union will be fired. “If the union stays,” Battaglini says, “the company will close.” And no one will receive a single cent of their severance pay. They will land on the street with nothing. Promotions, and the higher pay that goes along with them, will be given only to those who openly denounce and quit the union. Battaglini is trying to set up yet another yellow union, calling it a “Social Dialogue Commission,” which will of course be a promanagement body whose sole purpose would be to replace the real union. The company is now referring to the Independent Workers Union Edgar Roblero as the “black union.” On the other hand, management is calling the yellow union they are setting up the “white union.” human resource assistant director Manager Monica Osorno is telling the workers: “If you want to continue working here you must stop this organizing and join the good union.” Management openly promotes and supports their “white union” in every way they can, encouraging workers to affiliate. General Manager Battaglini taunts the union leaders. He shouts at the General Secretary of the union, Angel Avalos, who is a top mechanic: “If I order you to carry and throw out shit you will do it.” Of course, this violates the proper job descriptions contained in the contract. Battaglini is forcing the mechanics, where the leadership for the union is strongest, to carry garbage from one place in the factory to another. On June 27, human resource chief Hazel Herrera tried to fire union leader Bayron Miles Reyes, but through pressure from the union he was reinstated three days later. However, tired of the constant pressure and harassment management directed against the union, he resigned two months later. Earlier in May, the company fired union activist Julio Ramirez. His crime was that he missed work on May 15 because his brother died. On Monday, June 2, the Ministry of Labor in Granada, though the Department of Inspection, set up a meeting between General Manager Vincent Battaglini, Chief of Human Resources Hazel Herrera, and Angel Avalos of the Independent Workers Union Edgar Roblero. An agreement was signed where Battaglini says he will work very hard “in promoting dialogue with the representative of the workers and to respect the laws, the internal rules, and the collective contract.” On the part of the union, Angel Avalos affirmed that the union wants “socio-labor stability in the company” and is extremely anxious to return to “dialogue and better ways of communication with management.” Unfortunately, like so many other agreements signed, nothing has changed and KB management has kept up its assault to destroy the union and deny its workers their legal right to freedom of association. On September 2, as a form of reprisal and to isolate her from the other workers, management arbitrarily switched Ms. Dolores Roblero, the union’s secretary for women’s affairs, from her long held position as a line supervisor to the final inspection department. Not only is she now cut off from the workers, but no one has explained to her exactly how to identify where—to what production line or group of workers—to return defective jackets for repair. This has become a common strategy at the KB factory, with management frequently (even every week) switching the most active union members from one job to another. This forces union members to constantly master new operations, making it impossible for them to meet their new production goals. Not only do their wages drop, but if they make enough errors, management can fire them. When management did this to Dolores, many of the workers felt they had had enough and wanted a work stoppage, but the union convinced everyone to keep working. This was not the time for such a fight. General manager Battaglini shouted at the workers: “There are 50 people dying of hunger here in Granada who want to work if you don’t! Don’t you forget that!” The union is, of course, fighting this, pointing out that according to Article 31 of the labor code, a worker can only be switched to a different post by “mutual consent.” (“By mutual consent, the worker can be changed from one post to another in a provisional or definitive way, without implying a diminishing of labor conditions or other labor rights.”) • The company is doing everything it can to block the KB union representatives’ participation on the mixed commission on occupational health and safety, which has been granted official status by the Ministry of Labor through November 2004. The company wants to replace the independent union representatives with members from its newly formed yellow union, which has perhaps 20 members in comparison to the 78 percent of KB workers affiliated with the Independent Workers Union Edgar Roblero. On August 12, taking advantage of the absence of the union’s general secretary, Angel Avalos, general manager Battaglini attempted to pressure the other two union representatives, Lidilia Roblero and Guillermo Sandino Tellez, to resign. They refused. Now the company is ignoring the union and refusing to recognize its participation. • Illegal firing of union members continues. Recently, Yessenia Chavez was fired for missing two days of work while caring for her husband, Eduardo Antonio Dominguez Montiel, who had hemorhagic dengue—the worst form of dengue fever, which is excruciatingly painful and can result in death. Yessenia had a medical certificate from a local clinic—the Medical Company of Japan which many of the workers use—which she presented to the company. Still, for missing September 7 and 8, she was fired. The union is fighting this, since it is clearly an illegal firing. Article 74 of the Labor Code states: “The employer will grant permission or license in the following cases, for a period of not more than six working days for a serious illness of a nuclear family member who lives under the same roof, if the illness requires his/her indispensable presence.” Then, on September 11, Erlon Pilante was fired for being unable to work overtime twice in the month. Of course, by law, all overtime is supposed to be voluntary. In another violation of the contract, and without consulting the union, in August management started a night shift running from 6:00 p.m. to 3:20 a.m., a 10.3-hour shift, five nights a week. There are just 16 workers involved—working on the front operations of the jackets, such as sewing pockets—and management is treating this as a training period, telling the workers that they will eventually be incorporated into the regular day shift. However, the rule, as general manager Battaglini explains it, is that if any of these workers dare to affiliate to the union, they will never receive a permanent job with the company. These workers have no written contract, nor are they inscribed in the Social Security health care system. There are many other violations as well. Article 51 of the Labor Code clearly stipulates that night shifts cannot exceed seven hours a night, or 42 hours a week. Management told the workers when they entered the factory that they would receive a free dinner each night along with a 50 cordoba bonus ($3.34) for the week, until they learned the operations and could research the production goal. But the general manager has refused to follow through on these commitments, saying that he “can’t be throwing money around if they don’t know how to do anything and don’t do anything during the night shift.” In addition, the workers say it is extremely dangerous to get out of the factory at 3:20 a.m. when there is no public transportation. The union is pressing the factory to at least provide safe transportation for the workers. WHAT IS AT STAKE? The labor rights struggle – and its outcome – at Bayer Clothing / KB Manufacturing will have important consequences well beyond this one factory. For years, the workers in Nicaragua and Honduras have been among the most effective in Central America and the Caribbean in defending workers’ rights, and even establishing a handful of strong unions within the maquila, or export assembly sector. However, for the last year – and the workers say this is to clear the way, for the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTAA) and the Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) – there has been a concerted systematic attack by the companies to wipe out the maquila unions and roll back the labor rights victories that have been won. The KB Independent Workers Union Edgar Roblero is strong, smart, committed and has the overwhelming support of the workers. If such a union can be destroyed, then the corporate steamroller of anti-union repression will build up even more momentum, spelling doom for respect for worker rights across the entire region. With strong unions like the Independent Workers Union at KB out of the way, the Central America Free Trade Agreement can go forward knowing that the workers will have