The rehabilitation of male detainees at the Alexander Maconochie

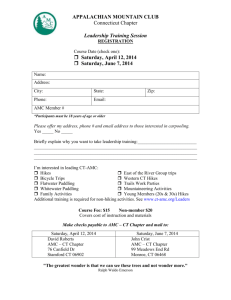

advertisement