The Discounted Cash Flow-based Valuation Methodology As Tested

advertisement

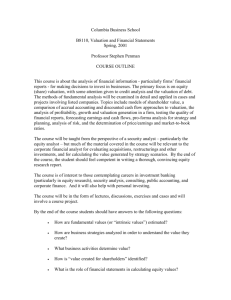

THE DISCOUNTED CASH FLOW-BASED VALUATION METHODOLOGY AS TESTED BY A PUBLIC MARKET TRANSACTION* George Athanassakos, Ph.D. Professor of Finance Ben Graham Chair in Value Investing Richard Ivey School of Business The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario N6A 3K7 (519) 661-4096 gathanassakos@ivey.uwo.ca * This article draws on Dr. Athanassakos’ monograph “Equity Valuation: A Guide to Discounted Cash Flow and Relative Valuation Methods” published by The Clarica Financial Services Research Centre, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, 1995. The monograph is currently printed and bound at The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario. THE DISCOUNTED CASH FLOW-BASED VALUATION METHODOLOGY AS TESTED BY A PUBLIC MARKET TRANSACTION I. Introduction Trends emerging in recent years, such as divestitures, spin-offs and class action suits to mention some, make an understanding of valuation of companies with ongoing operations imperative, not only for investors, but also for managers and for a company's directors. The Discounted Cash Flow Method (DCF) to valuation that will be discussed in this article will be a guide, first, to business managers in their attempt to follow value maximizing strategies; second, to portfolio managers and security analysts in their effort to discover the true economic value of a company and its equity; and third, to investment bankers in their advisory role of companies involved in merger transactions and restructuring. This article will not demonstrate how to value companies in financial distress, as, in such cases, a contingent claims valuation will be more appropriate. The DCF valuation method will be demonstrated through the valuation of a Canadian company, Canada Packers Inc., using actual financial data. II. Definition of Economic Value It is Economic Value (also referred to as fundamental value) that I am concerned with in this article, not market value, book value, break-up value or liquidation value. Economic value relates to the ability of an asset to provide a stream of after-tax cash flows to the holder. It is determined by assessing the asset's potential future cash flows and their associated risk. Economic value is a future-oriented concept. Moreover, it is important to understand that economic value is dynamic; new information about the future is constantly changing the view of an asset's economic value. III. The Framework of the Valuation Approach The DCF-based valuation method to be presented in this article is in the spirit of Capital Budgeting with which most readers should be familiar. The only difference is that unlike assets which usually have a finite life, a company is often assumed to have an infinite life. Moreover, for the application of capital budgeting to valuation, one will have to estimate cash flows starting with accounting figures. The DCF method to valuation has its foundation on the principle that the value of an asset is the present value of the expected cash flows resulting from the use of the asset. Three fundamental questions need to be answered in using this method. First, how are the cash flows defined? Second, for how long should cash flows be forecast? Third, what is the appropriate discount rate that converts future values into present ones? The answers to these questions will be dealt in detail below. There are two DCF methods to valuing the equity of a company. The Free Cash Flow Method (FCF), known as the entity approach, and the Equity as Residual Cash Flow Method (ERCF). According to the FCF method, the value of the entity as a whole is determined first and equity is estimated indirectly. The ERCF method arrives at the equity value directly. I prefer to use the FCF method for four reasons. First, discounting residual equity cash flows provides less information about the sources of value creation and is not as useful for identifying value creating opportunities. Second, since FCFs are before debt-related payments, they are much less likely to be negative and create problems in valuation than ERCFs. Third, using the FCF valuation approach, we do not have to consider explicitly the cash flows related to debt, as FCFs are before debt-related charges cash flows. However, interest rates and the capital structure of the company may still affect company (and eventually equity) value through their effect on the company's Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). Fourth, the two valuation approaches will eventually give the same equity value as long as consistent assumptions are made about growth, and as long as debt and debt-related instruments are valued correctly and the discount rates used to discount cash flows correctly reflect the riskiness of each cash flow stream. Exhibit 1 demonstrates the entity approach to (equity) valuation. It is seen that the market value of an entity (Exhibit 1, Panel A) is calculated as the present value of the company's total free cash flows over an explicit forecast period plus the present value of the terminal value plus excess cash and marketable securities plus the market value of non-operating assets plus the market value of excess real estate (after-tax) plus (minus) the market value of the company's pension plan over (under) funding. Once the market value of the company is estimated, the market value of equity (Exhibit 1, Panel B) is derived residually by subtracting the market value of short-term debt, long-term debt, capital leases, operating leases, preferred stock, minority interest and warrants and executive stock options from the estimated market value of the company. IV. The Free Cash Flow-Based Formula of Valuation and Related Definitions The value of the entire company, here ignoring the other components of an entity value referred to in Exhibit 1, Panel A, is equal to the present value of the company's free cash flows discounted by the appropriate discount rate. The components of a company's FCFs appear in Exhibit 21. FCFs do not incorporate any financing-related cash flows such as interest expenses or dividends. In other words, they reflect the cash flows generated by the company that are available to all providers of the company's capital. To be consistent, the discount rate applied to the FCFs should reflect the opportunity cost to all capital providers, adjusted for any tax benefit accruing to the company (i.e., the tax shield provided by the interest expense), and weighted by their relative contribution to the company's total capital. This is the definition of the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). 1 Amortization of Goodwill is no longer deductible for accounting purposes, and hence, in current applications, the deduction and add back of Amortization for Goodwill is not necessary. However, it is shown here as the valuation of Canada Packers takes place at a time when Amortization for Goodwill was still deductible. Similarly, in current applications, Accumulated Deferred Taxes have been replaced with the difference between Deferred Income Tax Liabilities and Deferred Income Tax Assets. In practice, rather than attempting to find the present value of the FCFs to infinity, given an ongoing operation, we separate the stream of FCFs into two parts. The first represents the stream of FCFs over an explicit forecast period and the other represents the terminal value of the FCFs occurring after the explicit forecast period, as shown below: n VAL0 E (FCFt ) t 1 (1 K ) t TVFn (1 K ) n where, VAL0 = The value of the company FCFt = The free cash flows to the company expected over the explicit forecast period K = The company's weighted average cost of capital n = The number of years of the explicit forecast period TVFn = The terminal value of the FCFs at the end of the explicit forecast period. Exhibit 3 defines terminal value. The value of equity is then determined residually by subtracting from VAL0 the market value of all items shown in Exhibit 1, Panel B. The background items needed for the estimation of FCFs are available from the company’s reported financial statements. While most analysts do a fairly adequate job in identifying these items and forecasting FCFs, they tend to overlook items that are non-operating and/or those that are off balance sheet, which are important and tend to be ignored at the analysts’ peril. I will come back to it in Section VIII. V. Steps in Performing a DCF Entity Valuation Exhibit 4 summarizes the steps necessary for an entity and eventually equity valuation. V.1 Forecasting Free Cash Flows Below, I outline the major areas of analysis one has to perform in order to effectively deal with forecasting free cash flows. While understanding the valuation technique and cash flow derivation are important, I can not stress enough the importance to an effective valuation of a thorough understanding of the company - its strengths and weakness, the industry - life cycle analysis, the dynamics of the industry and the competitive environment, as well as the economy and the big picture - short run and long run economic outlook, and an analysis of demographic trends and of the social, economic, political and regulatory forces that are expected to be dominant in the years to come. (a) Economic Analysis Economic analysis and forecasts provide an essential underpinning in industry and company projections. The outlook for the company sales and, eventually cash flows, depends on such macro-economic factors as, the growth in real Gross National Product, inflation, corporate profits, interest rates and so on. Economic forecasts can either be purchased from forecasting services or be developed by in-house economists. In any case, the company's sales projection should always start with an outlook of the economy, and culminate with an analysis of demographic trends and of the social forces that are expected to be dominant in the years to come. (b) Industry Analysis An analysis of the structure of the industry to which the company in question belongs will enable us to spot trends developing in the industry and project the industry sales more effectively. Industrial life cycle analysis and an analysis of the industry's growth potential are of great importance. As industry sales are at an aggregated level, their magnitude is easier to forecast than company sales. Following an industry sales forecast, we should investigate how the company's in question sales forecast relates to the industry and whether our forecast will cause the company's share of the industry to increase or decrease and whether this is consistent with the industry's competitive dynamics and environment. (c) Company Analysis c.1. Free Cash Flow Projections The outlook for the economy and the industry dynamics will help us make a projection of the company's sales over the explicit forecast period. A regression model that relates macroeconomic and sectoral statistics to the company's sales, and uses the outlook for the economy and industry as an input, will be the first step to the sales projections. Volume and price projections should be reflected in the sales forecasts. Qualitative adjustments to the regression based projections may also have to be made to take into account difficult to quantify or non-economic factors, such as demographic changes, free trade agreements, changes in consumer tastes and preferences and so on, which are expected to take hold in the future. As forecasting the company's income statement and balance sheet is generally demand driven, the sales projections will lead, given stable or well behaving historic relationships to sales, to projections of costs, inventories, accounts receivable, accounts payable and so on. Naturally, any trends emerging in cost control and profit margins, inventory control and terms of credit should also be reflected in the projections. Financial ratio analysis, both time series and cross sectional, is very important in company analysis. It will help us determine the company's strengths and weaknesses, how the company’s competencies compare with the industry, and whether the company's financial performance is improving or deteriorating over time. This will help the analyst’s growth rate projections. Financial ratio analysis is also informative in understanding the company's capital structure and investment/payout policies, which are important determinants in funding growth, cost of capital calculations and as input in the terminal value formulae. Once sales, costs, fixed assets and working capital projections are made, the analyst has to determine how the company intends to fund growth. The company's historic and expected investment/payout ratios have also to be calculated and estimated, respectively. The investment ratio of importance in the analysis I am following is the percentage of Net Operating Profits Less Adjusted Taxes Plus Amortization (NOPLATPA) that the company has retained, on average, for new investment purposes. The (total) payout ratio is one minus the above investment ratio. The company's marginal (expected) tax rate estimation (normally, the statutory tax rate) is another important consideration. For this estimation, one should consider not only the current tax regime, but also any known future tax reforms. Estimates of all the above will set a structure to the forecast of the income statement and balance sheet. The forecast of the income statement and balance sheet will lead to a forecast of free cash flows. An assessment of the riskiness of cash flows also has to be incorporated in the valuation exercise. Such an analysis will determine how the cash flows will be discounted to account for the time value and risk. Finally, it is particularly important that inflation be built into the components of the free cash flow forecast. The projections have to be in nominal terms for consistency reasons. As the discount rate is always estimated in nominal terms, the free cash flows in the numerator of the valuation formula also have to be in nominal terms. c.2 The Explicit Forecast Period The explicit forecast period should be sufficiently long to incorporate a number of developments. First, it should incorporate the full effects of restructuring efforts by the company. Second, it should incorporate the effect on cash flows of the full response of the company to a new competitor or product expected to enter the market. Third, it should capture a complete economic cycle of the company's operations in order to introduce realism and consistency in the terminal value estimation. Fourth, in the case of a merger, the explicit forecast period should incorporate the full effect of the expected synergies as a result of the merger. In effect, the explicit forecast period should reflect growth rates of the company's cash flows that are above or below industry norms and should extend until we believe that the company has reached a steady state of growth. Steady state means that the company expects to earn, on average, a constant rate of return on new projects during the post-explicit forecast period, and also expects to invest, on average, a constant proportion of its cash flows into the business each year. As a result, understanding a company’s stage in its life cycle is of paramount importance in deciding the appropriate length for the explicit forecast period. c.3 The terminal Value The prospects of a company beyond the explicit forecast period become part of the terminal value portion of the FCFs formula, and assumptions. As a result, terminal value accounts for the present value of cash flows of an ongoing operation following the explicit forecast period. Both of the terminal value formulae reported in Exhibit 3 can be derived from the general asset valuation formula that defines the value of an asset as the present value of its expected cash flows to infinity. If, in that general formula, we assume that cash flows grow at a constant growth rate (g) for ever, that the Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) and the company's Retention Ratio (b) also remain constant for ever, and that depreciation equals replacement investment, the general valuation formula collapses into terminal value formula (1). Terminal value formula (2) is derived from formula (1) under the further assumption that ROIC equals WACC. NOPLATPA should reflect the last year of the explicit forecast period. All trends and assumptions of the explicit forecast period should be reflected in the base NOPLATPA used for the terminal value. ROIC should be consistent with the expected competitive environment. Economic theory suggests that competition will eventually eliminate supernormal profits, so that it may be more appropriate to set ROIC equal to WACC; this gives more validity to terminal value formula (2). The retention ratio should not only reflect recent trends, but also projections about the company's needs for further investment when a steady state is reached. As the company matures, the need for new investments will be diminished and more funds will be made available to claimholders. As a result, the input in the terminal value formulae for the retention ratio should be lower than the company's historical average retention ratio. The long-run growth rate should be consistent with ROIC and b. It should be kept in mind, however, that few companies can be expected to grow faster than the economy, or even the industry average for a long time period. The terminal value formulae are very sensitive to the growth rate assumption, so that one should be extremely careful in forecasting the growth rate to incorporate in the terminal value formulae. When all assumptions are incorporated in the terminal value formula and a terminal value is arrived at, this value should be discounted by (1 + WACC) raised to the appropriate power needed to bring this value to the present and then added to the present value of the explicit forecast period free cash flows to determine the value of the company from operations. VI. The Discount Rate The WACC is given by the following general formula: p m OB j Si PF n WACC K dq (1 Tc ) K pf K si K obj V V V V q 1 i 1 j 1 Bq where, Kdq = The before-tax yield-to-maturity of straight debt (q = short or long-term debt) and leases (q = operating or capital leases) Tc = The marginal tax rate of the company Bq/V = The target weight for straight debt and leases in total firm capitalization Kpf = The after-tax cost of preferred stock PF/V = The target weight for preferred stock in total firm capitalization Ksi = The after-tax cost of equity or equity-like capital (i = common equity, warrants or stock options) Si/V = The target weight for equity and equity-like capital in total firm capitalization Kobj = The after-tax yield of non-straight debt or hybrid securities (j = callable bonds, extendible bonds, convertible bonds, bonds with warrants, etc.) OBj/V = The target weight for non-straight debt or hybrid securities in total firm capitalization V = Total firm capitalization All of the components in the WACC formula have to be estimated. I will deal with the most important components of the WACC estimation below. VI.1 The Cost of Common Equity The most commonly used model for estimating the cost of equity is the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). It is shown below: Ks Rf E Rm Rf where, Ks = The cost of common equity Rf = The risk-free interest rate ß = The beta coefficient, a measure of the systematic risk of common equity E(Rm) = The expected rate of the return on the market portfolio E(Rm) - Rf = The expected (equilibrium) market risk-premium. As it is obvious from the model above, to properly estimate the cost of equity using the CAPM, one needs estimates of the risk-free rate, the beta coefficient and the market risk-premium. Although the discussion can get complicated, in practice, the risk-free rate is approximated by the current long-term government of Canada bond yield-to-maturity. The expected risk-premium used is the arithmetic mean of the difference in the returns on the market portfolio (i.e., TSX300) and the returns on the long-term government of Canada bonds over the period 1926 to present. These averages are provided in reports produced by Boyle, Panjer and Sharpe from the University of Waterloo. An estimate of the beta coefficient can be obtained by subscribing to a service that provides such estimates, namely, BARRA inc., Value Line or the Polymetric Report. Alternatively, one can estimate his/her own beta coefficient of a stock by running a regression of the stock’s total returns against the total returns on the market portfolio (i.e., TSX-300). Many issues can arise in estimating the beta coefficient, but these issues are beyond the scope of this article. Other models also exist for the calculation of the cost of equity such as the bond-plus risk premium model, the arbitrage pricing model and the constant dividend growth model. When data are available all methods, with the exception of the dividend growth model, can be used and an average be calculated as the best approximation of the cost of equity. VI.2 The Cost of Debt The cost of short-term debt can be taken to be the rate that the company has, or similarly rated companies have, to pay to raise short-term debt. The cost of long-term debt, capital leases and operating leases can be taken to be the yield-to-maturity on the company's long-term debt, or of similarly rated companies, if the company's long-term debt does not trade. All the above costs have to be calculated eventually on an after-tax basis by multiplying the corresponding rates by one minus the company's marginal tax rate, as these costs are all deductible for tax purposes. VI.3 Costs of Other Components of the Balance Sheet The cost of preferred equity is the ratio of preferred dividend per share to the price per share of preferred equity. It is already in after-tax terms. If preferred equity does not trade, one can use the yield of similarly rated preferreds as a proxy. The cost of callable, convertible and other bonds with embedded options are more difficult to estimate as knowledge of options theory is necessary. The same holds for estimating the cost of warrants and executive stock options2. In practice, one has to seriously consider these items only if they constitute a large proportion of the company's capital structure. VI.4 The Capital Structure Question Once the cost components have been estimated, one will need to know the appropriate weights to use to weigh the cost components in order to arrive at the overall cost of capital. The weights represent the proportion of each security that the company has used to fund growth in total funding. There are many issues that arise with regards to the appropriate weights. Are the weights calculated in market value or book value? Are the weights the current market value or do they represent the company's target capital structure? The proper weights to use are the target weights of the company for the following reasons. First, the company's actual capital structure may not reflect the capital structure expected to prevail in the long run. Even if both are the same initially changes in the business environment can cause the actual and the target capital structures to eventually differ. Second, the target capital structure solves the problem of circularity involved in estimating the WACC. That is, if we know the market value of the liability side components what do we need the WACC for? Third, given that the target capital structure is the one that the company tries to maintain in the long run, the target capital structure is the best indicator of the future capital structure. Finally, in many cases, we may be unable to estimate the company's market value weights, especially if the company in question is privately held. The current market value weights, however, are useful to estimate for comparative purposes and for getting an idea of the company's target capital structure. A historic average of market value weights should give us an approximation of the company's target capital structure. This should not be too far from the average of similar companies in the industry. By paying lower salaries to executives than otherwise, “executive stock options” become another means by which a company finances its operations. 2 VI.5 Inflation and the WACC No adjustment for inflation has to be made in the WACC estimation, as the WACC components are market-determined and are, thus, already in nominal terms. VII. Sensitivity and Scenario Analysis Because the projections of the various valuation components are estimates, subject to various degrees of errors, one should carry out sensitivity or scenario analysis of the valuation exercise to gain a better appreciation of the potential errors involved in the forecasting process and their effect on valuation. These sensitivity/scenario tests will not only assist in the development of a refined and well conceived forecast, but also become a significant input into the determination of the overall risk inherent in the projections and the valuation of the company. Finally, as all forecasting and valuation exercises are subjective, it is quite appropriate that one attempts to triangulate his/her the DCF-based value of the equity by using other methods of valuation, such as the relative valuation method (i.e., the multiples approach) and/or valuation from the divisions up. VIII. Non-Operating Assets, Off Balance Sheet Items and the Value of Equity Assuming the company has only cash flows from operations and (except for executive stock options) only on-balance sheet items, the FCFs method to valuation arrives at the value of the entity by the adding the present value of FCFs over the explicit forecast period to the present value of the terminal value. From this value, the value of short and long term debt, as well as the value of any preferred shares and capital leases are deducted to arrive residually at the value of equity. The value of executive/employee stock options must also be deducted, as otherwise the value of equity will be biased upwards given that FCFs have been biased upwards by understating the company’s cost of salaries3. In other words, all current means of raising funds, in market values, have to be deducted from the value of entity to arrive at the value of equity. Any future issuance of securities is irrelevant to valuation. Most companies, however, also have non-operating and/or off balance sheet items, which, while we did not deal with when forecasting FCFs earlier, are nevertheless important and key to entity and equity valuation. These are: Excess Cash and Marketable Securities: These are the marketable securities in which the company has parked its funds in the short term until profitable investments are identified. The cash flows from such investments were not part of the forecasted FCFs above and hence the value of such securities has to be explicitly added to the above-derived value of the entity. 3 In terms of valuation, the current debate of whether executive stock options should be expensed is a mute one as the market, to arrive at the value of equity, has already deducted the value of the executive stock options from entity value. Excess Real Estate: This is land or buildings that are carried in the books for minimal amount and, at this point, stand idle awaiting development, renovation, and so on. These assets are not currently producing any operating cash flows, but nevertheless are not without any value. They do have value, which, in may cases is quite high, and such a value has to be added (in after tax terms) to the above-derived value of entity. Non-Operating Assets (Investment and Advances): These are investments companies have made in other companies’ operations and, as a result, they were not part of the FCF forecast made above to arrive at the value of entity. The market value of such investment has to be determined and added to the above estimated entity value. Defined Benefits Pension Plan: Companies that have defined benefits plans collect employee as well as their own contributions to the company’s pension plan and hire a professional manager to manage this sum on behalf of the company and employees. The pension plan has a balance sheet of its own, which, however, is not consolidated in the company’s reported balance sheet. The asset side of the balance sheet represents the market value of the investments the pension plan manager has made in stocks, bonds and so on. The liabilities of the pension plan represent the present value of the promised pension payments the company has made to future retired employees. If assets exceed liabilities the pension fund is said to be over funded and if liabilities exceed assets, the pension fund is said to be underfunded. If the fund is underfunded, the company has to make up the difference. This money will come out of the company’s FCFs. These potential outflows were not accounted for in the projections of FCFs earlier. As a result, a company with underfunded pension plan has a hidden liability, as it owes money to the plan. The deficit, being a liability, has to be deducted from the value of the entity arrived at earlier. As any company payments towards covering such deficit will be tax deductible, the deficit deducted from the company value should be in after tax terms. If the pension plan is over funded, it is not clear who owns the surplus. However, a company with an over funded pension plan may be allowed to take a contribution holiday. The saved payments indirectly go to the pocket of equity holders. To be symmetric then an over funded pension balance should be added to the entity value (in after tax terms). An Off Balance Sheet Liability that (along with the other on balance sheet liabilities) has to be deducted from the entity value to residually arrive at the equity value is Operating Leases. Operating leases are a liability such as capital leases or debt, but are not shown in the company’s balance sheet. We have to estimate the value of operating leases, by capitalising the payments, shown in the notes to financial statement, by the cost of debt and deduct this value from the value of entity as we did with the on balance sheet debt. This, as well as, information regarding other off-balance sheet commitments and potential liabilities, such as Lawsuits and Environmental Obligations that may come to haunt the company, are all buried in the notes to financial statements which have to be read very carefully by analysts. Any questions or doubts about such items have to be taken up with and clarified by the company, if analysts want to properly estimate the value of equity. IX. Application of the DCF Valuation to Canada Packers Inc. The application of the valuation approach discussed above will be demonstrated via the valuation of Canada Packers Inc. (CP), one of the largest publicly held Canadian companies in the food processing business. The date of the valuation is the end of March 1990, just a few months prior to the merging of CP with Maple Leaf Mills Ltd. At the time, CP’s stock was trading on the TSE at $14 1/8. Exhibit 5 provides some relevant financial statistics for CP. Exhibit 6 reports the forecasted free cash flows for CP over the explicit forecast period, taken to be five years. First, sales were forecasted and most other items of the balance sheet and income statement were then derived as a proportion of sales. It was assumed that the industry sales would grow by the average forecasted CPI-Food. No real growth was forecasted as population growth was assumed to remain flat over the foreseeable future. CP, which had underperformed the industry substantially over the 1985 to 1990 period, was assumed that it would continue to underperform the industry, but to a lesser extend. By the end of the explicit forecast period, CP’s growth rate was assumed to match that of the industry, as the restructuring and reorganization under way were assumed to bear fruit. Sales growth was assumed to be financed with long-term debt in order for the total debt to capital to remain close to the desired debt ratio, assumed to be its historic average, which was also close to the industry ratio of 28% - 32%. No new equity was assumed to be issued to fund growth as it may have raised issues of control with the McLean family which held a large percentage of the company’s equity. The company’s rating of “A” was assumed to be maintained, as debt ratios were forecast to remain at acceptable levels. The steady state growth rate for inclusion in the terminal value formulae was assumed to be 6%, the longterm expected growth rate of sales, which was the long-term expected growth rate of the CPIFood Index. From 1995 on, CP was assumed to retain 60% of its NOPLATPA for new investments. This long-term retention ratio was close to the average retention ratio for the period 1985-1995, lower than the high investment years of 1985-1990, but higher than the low investment years of 1991-1995. Having forecasted FCFs, I next estimated the WACC. I used the CAPM for the estimation of the cost of equity. The beta was taken from the Polymetric Report to be 0.42. The expected market risk- premium at the time was calculated by Boyle, Panjer and Sharpe to be 0.067. At of March 31, 1990, the long-term government of Canada yield was 0.1095. Putting all these into the CAPM formula, I arrived with a cost of equity of 0.1376. Other methods used also gave a rate close to 0.1376. The cost of short-term debt was taken to be the prime corporate rate at the time; it was 0.1341. The costs of long-term debt and operating leases were taken to be the average yield on “A” rated companies supplied by the Canadian Bond Rating Service. I also estimated the cost of employee stock options using the Black and Scholes option pricing formula adjusted for dividends. It was not that important to estimate the cost of stock options as they represented a small amount of the company’s capital structure, but I did it for demonstration purposes. The target capital structure weights were taken to be the long-term average ratios of the various liability items in the total CP capitalization. They were close to the industry average, and the company’s current market value weights. Exhibit 7 summarizes the current market values, the market value weights (target weights) and the WACC estimation. CP’s WACC was estimated to be 0.1174. I now have all the information I need for the DCF-based valuation of CP and its equity. Exhibit 9 summarizes CP’s valuation. It is seen that CP’s price per share was estimated to be between $13.35 and $14.50, a range within which CP’s stock was trading at the time. I triangulated the valuation using the relative valuation approach and the divisional approach and found prices per share of $14.75 and $14.59, respectively. The closeness of all valuation estimates increased my confidence in the valuation of CP and its equity. I also carried out sensitivity analysis. Valuation was not very sensitive to most variables, with the exception of the profit margin. Even a small improvement in CP’s profit margin would almost double the company’s value. No wonder CP and the resulting companies have been subject to mergers/acquisitions on so many occasions. Exhibit 1 USING THE DCF APPROACH TO VALUATION: AN EXAMPLE OF VALUING AN ENTITY AND ITS COMMON EQUITY +800 +100 =5200 Pension Fund Over (Under) Funding (A/T) Value of Company 5000 4500 +400 +2600 4000 +100 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1200 1000 500 0 Value of Free Cash Flows Over Explicit Forecast Period Present Value of Terminal Value Excess Cash & Marketable Securities NonOperating Assets Excess Real Estate (A/T) Panel A: Entity Valuation Exhibit 1 (continued) USING THE DCF APPROACH TO VALUATION: AN EXAMPLE OF VALUING AN ENTITY AND ITS COMMON EQUITY 5200 -2000 5000 4500 4000 3500 -300 -200 3000 -100 -200 =2400 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 Value of Company Short and Long-Term Debt and Capital Leases Value of Operating Leases Preferred Stock Minority Interest Warrants & Executive Options Panel B: Equity, as a Residual, Valuation Value of Common Equity Exhibit 2 FREE CASH FLOW DEFINITIONS Revenues Cost of Goods Sold Selling, General and Administrative Expenses Depreciation Amortization for Goodwill + Implied Interest on Operating Leases = Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) Taxes on EBIT +/Increase/Decrease in Accumulated Deferred Taxes = Net Operating Profits Less Adjusted Taxes (NOPLAT) + Amortization for Goodwill = Net Operating Profits Less Adjusted Taxes Plus Amortization for Goodwill (NOPLATPA) + Depreciation = Gross Cash Flows -/+ Increase/Decrease in Working Capital Capital Expenditures Increase in Capitalized Operating Leases Investment in Goodwill = Free Cash Flows from Operations + Non-Operating Cash Flows +/Increase/Decrease in Foreign Currency Translation Adjustments = Total Free Cash Flows Exhibit 3 TERMINAL VALUE FORMULAE TVF1,n = TVF2,n = NOPLATPA n 1 g 1 b K g NOPLATPAn 1 g K → assumes g, r, b are constant (1) → also assumes K = r (2) NOPLATPA is defined in Exhibit 2. K is the WACC, g is the constant growth rate to infinity, r is the return on invested capital, and b is the retention ratio. These formulae are discussed in detail in Section V.1 (c.3). Exhibit 4 STEPS IN PERFORMING A DCF VALUATION Forecast free cash flows Collect historical data for the company and its comparables Decide on an explicit forecast interval Period of supernormal/ subnormal growth Use correct definition of free cash flows Use the marginal tax rate Estimate the cost of capital Estimate the continuing value Calculate market-determined Choose appropriate continuing opportunity cost of capital (terminal) value assumptions Use target capital structure weights Use the marginal tax rate Use NOPLATPA and assume: - replacement investment is equal to depreciation - retention ratio (b) captures new investment Match the formula used to the assumptions Calculate the result Triangulate the DCF value using other indicators, such as the multiples approaches Test and evaluate scenarios Sensitivity analysis Exhibit 5 Relevant Financial Statistics for Canada Packers Inc. as at March 31, 1990 ($ millions, except otherwise indicated) Excess Cash and Marketable Securities $1.1 Investments and Advances $5.1 Estimated Market Value of Excess Real Estate (A/T) Underfunded Pension Fund Sales Revenue $380.0 $5.2 $2,971.3 Other Relevant Statistics: Beta Coefficient 0.42 Prime Corporate Paper Rate 13.41% Government of Canada Long-Term Bond Yield 10.95% Yield to Maturity for “A” Rated Companies 12.45% Common Shares Outstanding (millions) 36.1 (Expected) Marginal Tax Rate 42% Exhibit 6 Canada Packers Inc. Projected Free Cash Flows Years Ended March 31 ($ millions) 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 2,993.3 3,015.4 3,037.8 3,060.2 3,082.9 (2,676.3) (2,694.0) (2,711.8) (2,729.7) (2,747.8) (227.8) (229.5) (231.2) (232.9) (234.6) (35.8) (37.7) (39.7) (41.8) (44.0) 6.0 6.0 6.1 6.1 6.1 59.3 60.3 61.1 61.9 62.7 (24.9) (25.3) (25.7) (26.0) (26.3) 1.0 1.6 3.0 3.2 3.3 35.4 36.6 38.5 39.1 39.7 4.6 4.6 4.6 4.6 4.6 NOPLATPA 40.0 41.2 43.1 43.7 44.3 Depreciation 31.2 33.1 35.1 37.2 39.4 Gross Cash Flow 71.3 74.3 78.1 80.9 83.7 Change in Working Capital (3.3) 3.9 (3.4) 3.1 1.8 Capital Expenditures 18.3 35.3 37.3 39.4 41.6 1.6 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 Investment in Goodwill/Intangibles (0.0) (0.0) (0.0) (0.0) (0.0) Gross Investment 16.5 39.6 34.2 42.8 43.8 Operating Free Cash Flow 54.7 34.7 43.9 38.0 39.9 Non-Operating Cash Flow 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Change in Foreign Currency Translation Adj. 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 54.8 34.7 43.9 38.0 39.9 Sales Revenue Cost of Goods Sold Selling, G&A Expenses Depreciation/Amortization Implied Interest on Operating Leases EBIT Taxes on EBIT Change in Deferred Taxes NOPLAT Amortization of Goodwill Incr. In Capitalized Operating Leases Total Free Cash Flow Exhibit 7 THE WEIGHTED AVERAGE COST OF CAPITAL CALCULATION Market Values ($ millions) Weights* Cost of Capital Weighted Average Cost of Capital Short-Term Debt $102.80 0.1364 0.1341 × (1-0.42) 0.0106 Long-Term Debt 92.86 0.1233 0.1245 × (1-0.42) 0.0089 Operating Leases 46.30 0.0615 0.1245 × (1-0.42) 0.0044 509.91 0.6768 0.1376 0.0931 1.48 0.0020 0.1919 0.0004 Common Equity Stock Options $753.35 0.1174 *Assumed to be the target capital structure weights as they are close to industry and company historical averages. Exhibit 8 DETERMINATION OF THE VALUE OF CANADA PACKERS INC. AND ITS EQUITY PANEL A: DETERMINATION OF THE VALUE OF THE COMPANY VAL0 Vfcf ,0 TVF0 Vfcf ,0 54.8 34.7 43.9 38.0 39.9 $155.59 million 1.1174 1.1174 2 1.1174 3 1.1174 4 1.1174 5 44.3(1 0.06)(1 0.60) $327.23 million 0.1174 0.06 TVFn,1 and discounting this to the present TVF0,1 or, TVFn,2 and discounting this to the present TVF0,2 327.23 1.1174 5 $187.85 million 44.3(1 0.06) $399.98 million 0.1174 399.98 1.1174 5 $229.61 million The Value of the Free Cash Flows from operations is: VAL0,1 Vfcf ,0 TVF0,1 $343.44 million or, VAL0,2 Vfcf ,0 TVF0,2 $385.20 million The Value of the Company is: VF VAL0 ECMS NOA ATUPF ATERE where, ECMS = NOA = ATUPPF= ATERE = excess marketable securities = $1.1 million non-operating assets = $5.1 million underfunded pension fund, after-tax = $5.2 million (1-0.42)=$3.02 million excess real estate, net of expected capital gains taxes on disposition = $380 million VF1 $726.62 million = or VF2 = $768.38 million PANEL B: DETERMINATION OF THE VALUE OF THE EQUITY AND PRICE PER SHARE The Value of Equity is: VE=VF - Debt – Operating Leases – Minority Interest – Stock Options VE1 = $726.62 - $195.7 - $46.3 - $1.4 - $1.5 VE2 = $523.48 million = $481.72 million or, Dividing by the number of shares outstanding, we obtain the following range for the price per share: P0,1 = $13.35 or P0,2 = $14.50