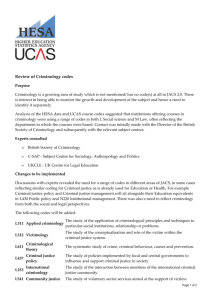

Critical Perspectives on Green Criminology

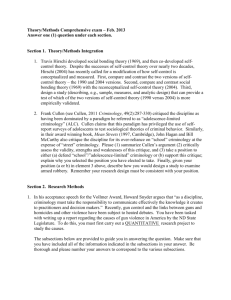

advertisement