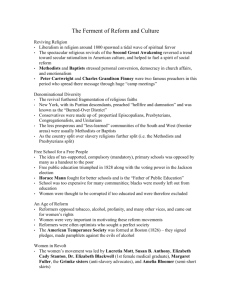

The Political Economy of Business Environment Reform

advertisement