The Relationship of Optimism and Hopefulness in Hospital Employees

advertisement

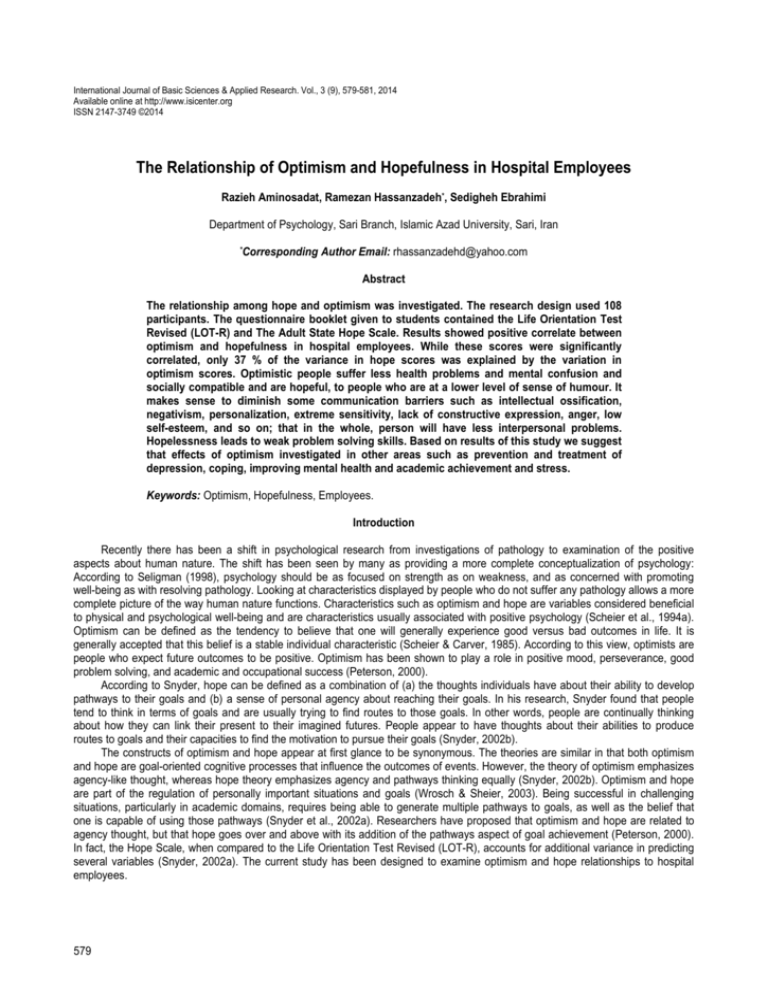

International Journal of Basic Sciences & Applied Research. Vol., 3 (9), 579-581, 2014 Available online at http://www.isicenter.org ISSN 2147-3749 ©2014 The Relationship of Optimism and Hopefulness in Hospital Employees Razieh Aminosadat, Ramezan Hassanzadeh*, Sedigheh Ebrahimi Department of Psychology, Sari Branch, Islamic Azad University, Sari, Iran *Corresponding Author Email: rhassanzadehd@yahoo.com Abstract The relationship among hope and optimism was investigated. The research design used 108 participants. The questionnaire booklet given to students contained the Life Orientation Test Revised (LOT-R) and The Adult State Hope Scale. Results showed positive correlate between optimism and hopefulness in hospital employees. While these scores were significantly correlated, only 37 % of the variance in hope scores was explained by the variation in optimism scores. Optimistic people suffer less health problems and mental confusion and socially compatible and are hopeful, to people who are at a lower level of sense of humour. It makes sense to diminish some communication barriers such as intellectual ossification, negativism, personalization, extreme sensitivity, lack of constructive expression, anger, low self-esteem, and so on; that in the whole, person will have less interpersonal problems. Hopelessness leads to weak problem solving skills. Based on results of this study we suggest that effects of optimism investigated in other areas such as prevention and treatment of depression, coping, improving mental health and academic achievement and stress. Keywords: Optimism, Hopefulness, Employees. Introduction Recently there has been a shift in psychological research from investigations of pathology to examination of the positive aspects about human nature. The shift has been seen by many as providing a more complete conceptualization of psychology: According to Seligman (1998), psychology should be as focused on strength as on weakness, and as concerned with promoting well-being as with resolving pathology. Looking at characteristics displayed by people who do not suffer any pathology allows a more complete picture of the way human nature functions. Characteristics such as optimism and hope are variables considered beneficial to physical and psychological well-being and are characteristics usually associated with positive psychology (Scheier et al., 1994a). Optimism can be defined as the tendency to believe that one will generally experience good versus bad outcomes in life. It is generally accepted that this belief is a stable individual characteristic (Scheier & Carver, 1985). According to this view, optimists are people who expect future outcomes to be positive. Optimism has been shown to play a role in positive mood, perseverance, good problem solving, and academic and occupational success (Peterson, 2000). According to Snyder, hope can be defined as a combination of (a) the thoughts individuals have about their ability to develop pathways to their goals and (b) a sense of personal agency about reaching their goals. In his research, Snyder found that people tend to think in terms of goals and are usually trying to find routes to those goals. In other words, people are continually thinking about how they can link their present to their imagined futures. People appear to have thoughts about their abilities to produce routes to goals and their capacities to find the motivation to pursue their goals (Snyder, 2002b). The constructs of optimism and hope appear at first glance to be synonymous. The theories are similar in that both optimism and hope are goal-oriented cognitive processes that influence the outcomes of events. However, the theory of optimism emphasizes agency-like thought, whereas hope theory emphasizes agency and pathways thinking equally (Snyder, 2002b). Optimism and hope are part of the regulation of personally important situations and goals (Wrosch & Sheier, 2003). Being successful in challenging situations, particularly in academic domains, requires being able to generate multiple pathways to goals, as well as the belief that one is capable of using those pathways (Snyder et al., 2002a). Researchers have proposed that optimism and hope are related to agency thought, but that hope goes over and above with its addition of the pathways aspect of goal achievement (Peterson, 2000). In fact, the Hope Scale, when compared to the Life Orientation Test Revised (LOT-R), accounts for additional variance in predicting several variables (Snyder, 2002a). The current study has been designed to examine optimism and hope relationships to hospital employees. 975 Intl. J. Basic. Sci. Appl. Res. Vol., 3 (9), 579-581, 2014 Methodology The research design used 108 participants based on Krejce and Morgan (1986). The questionnaire booklet given to students contained the the Life Orientation Test Revised (LOT-R) and The Adult State Hope Scale. Instrumentation Domain specific hope scale (DSHS) The DSHS measures an individual’s level of dispositional hope in relation to 6 life areas– social, academic, family, romance / relationships, work / occupation, and leisure activities. Scoring: respondents are asked to rate the importance of and satisfaction in the 6 life areas using Likert scales (ranging from 0 to 100). For each life area, respondents are also asked to rate the extent to which the item applies to them on an 8-point Likert scale (1=Definitely False, 8=Definitely True). A total score for the DSHS is obtained by summing the scores across the 48 items. Scores for each of the life areas can be obtained by summing the 8 items within each life area. Reliability: The DSHS demonstrates adequate internal consistency with an overall alpha of .93, and alphas for the life areas ranging from .86 to .93. Validity: demonstrates adequate concurrent construct validity. Miller hopefulness questionnaire This test is a diagnostic test that contains 48 questions; it is an aspect of hopefulness and frustration that the mentioned items have been chosen based on overt or covert behavioral manifestations in hopeful or desperate people. The questionnaire range is based on the Likert scale (strongly disagree with score 1 …. strongly agree with score 5), in which each person scores by selecting a sentence that describes his conditions correctly. The range of obtained scores is variable from 48 to 240 and if one earns 48 scores, he is considered completely helpless and the score of 240 indicates maximum hopefulness. Scores below 144 indicate low hopefulness and scores above 144 show high hopefulness. 12 questions of Miller questionnaire (11, 13, 16, 18, 25, 27, 28, 31, 33, 34, 38 and 39) consist of negative items and their evaluation and scoring are calculated reversely. Many studies have reported acceptable validity (Gholami et al., 2010) of the questionnaire and the reliability of the questionnaire has been calculated by Cronbach's alpha and bisection methods respectively as 0.9 and 0.89 (Naderi & Hosseni, 2010). Results Optimism index Mean of optimism score in participants was 37.2, maximum and minimum score was 47 and 31 respectively, with SD=4.803 that descriptive analysis showed in table 1. Table 1. Descriptive analysis of optimism index for participants. Variable Optimism N 108 Mean 37.2 Min 31 Max 47 SD 4.803 Hopefulness index Descriptive analysis showed that mean of hopefulness in hospital employees is 316.3 and has SD=33.81, while maximum and minimum score was 381 and 216, respectively (Table 2). Table 2. Descriptive analysis of hopefulness index for participants. Variable Hopefulness N 108 Mean 316.3 Min 216 Max 381 SD 33.81 Relationship between hopefulness and optimism Pearson coefficient showed that between hopefulness and optimism is significance correlation. But coefficient rate is relatively low (0.37) that showed with increase in optimism, employees hopefulness is increased (Table 3). Table 3. Pearson coefficient between hopefulness and optimism. Hopefulness-optimism 985 N 108 R 0.37 df 106 α 0.000 Intl. J. Basic. Sci. Appl. Res. Vol., 3 (9), 579-581, 2014 Discussion and Conclusion Several of findings suggest important differences between hope and optimism. While these scores were significantly correlated, only 37 % of the variance in hope scores was explained by the variation in optimism scores. Hope is formally defined as a positive motivational state that comprises two components which are the agency and pathways components (Rand, 2009). The agency component is the motivational component of hope that is used to initiate and sustain the movement toward achieving a goal (Snyder et al., 1991). The pathways component refers to the perceived ability in generating successful routes to attain the given goal (Snyder et al., 1991). Optimism is defined as a stable tendency to believe that good rather than bad things will happen (Scheier et al., 1994b). In optimism, the general positive outcome expectation is the central determinant of persistent efforts in attaining the desired positive goal (Scheier et al., 1994b; Rand, 2009). The major distinction between the two constructs is that hope emphasizes the individual motivation and perceived successful pathways that will play an integral part in developing positive outcome expectancies in comparison to optimism in which the focus is on particular actions that may bring those positive events (Rand, 2009). Specifically, greater hope and optimism would positively motivate the desired attitude towards achieving a desired outcome (Rand, 2009). Optimistic people suffer less health problems and mental confusion and socially compatible and are hopeful, to people who are at a lower level of sense of humour. It makes sense to diminish some communication barriers such as intellectual ossification, negativism, personalization, extreme sensitivity, lack of constructive expression, anger, low self-esteem, and so on; that in the whole, person will have less interpersonal problems. Hopelessness leads to weak problem solving skills. Hopelessness cause that patients constantly evaluate their experiences in the form of negative and results in bad or disturbing to consider problems. Optimism can be important coping skills for life problems. Snyder (2002a) found that between high hope and positive emotions and low hope negative emotions there was a significant correlation. Based on results of this study we suggest that effects of optimism investigated in other areas such as prevention and treatment of depression, coping, improving mental health and academic achievement and stress. References Gholami M, Pasha GH, Sodani M, 2010. To investigate the effectiveness of group logotherapy on the incensement of life expectancy and health on female teenager major thalassemia patients of Ahvaz city. Knowledge. 11(42): 23-42. Naderi F, Hosseni M, 2010. On the relationship between life expectancy and psychological perseverance: a case study of male and female students of Azad University of Gachsaran. Journal of Woman and Society. 1(2): 23-42. Peterson C, 2000. The future of optimism. American Psychologist. 55: 44-55. Rand KL, 2009. Hope and optimism: latent structures and influences on grade expectancy and academic performance. J Pers. 77(1): 231-260. Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW, 1994a. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and selfesteem): a reevaluation of the life orientation test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 67(6): 1063-1078. Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW, 1994b. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and selfesteem): a reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 67: 1063-1078. Seligman MEP, 1998. Positive social science. APA Monitor. 29: 2-5. Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, 1991. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol. 60: 570 585. Snyder CR, 2002a. Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry. 13: 249-275. Snyder CR, Shorey H, Cheavens J, Pulvers KM, Adams V, Wiklund C, 2002b. Hope and academic success in college. Journal of Educational Psychology. 94: 820-826. Wrosch C, Scheier MF, 2003. Personality and quality of life: the importance of optimism and goal adjustment. Quality of Life Research. 12: 59-72. 985