Strategic Analysis

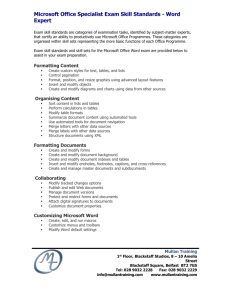

advertisement