Course Reader - GEGA: Global Equity Gauge Alliance

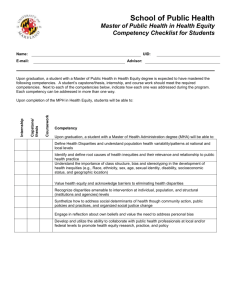

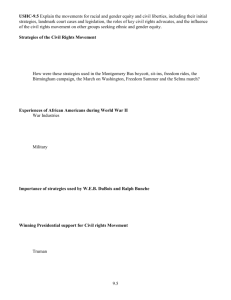

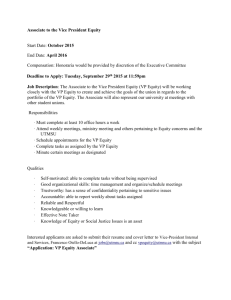

advertisement