Prof. Orth (Fall 2005)

advertisement

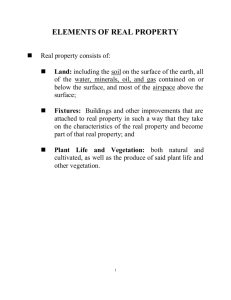

Property I. Personal Property A. Finding i. Classification of Personal Property— 1. Abandoned property—intentional relinquishment of possession and ownership of property. The finder of abandoned property gets ownership if they take possession of it. 2. Lost property—lost property is such that the owner does not know where it is and does not come back to claim it. The finder has a duty to reasonably protect the property (bailment) and return it or the value if the real owner shows up. 3. Mislaid property—property that was placed by the owner in a place where they may come back for it. The owner of the real property where the personal property was mislaid has a bailment to keep the property safe for the owner, should they return. ii. Cases— 1. Goddard v. Winchell—meteorite was part of the real property—showed the distinction between real and personal property—real property includes all objects growing out of the land or attached to the land. 2. Eads v. Brazelton—Steamboat America at bottom of Mississippi river. If you find something but cannot possess it and someone else comes along that can possess then they get it. 3. Armory v. Delamirie—chimney sweep’s boy finding the ring. A finder of personal property holds a better title against all of the world except for the actual owner. 4. Bridges v. Hawkesworth—salesman finds money on floor of shop (in public area of store) and salesman keeps. This was lost property and so the finder had the better title. Also it was found in the public space of the store. 5. South Staffordshire Water v. Sharman—worker finds rings in pool, owner had no knowledge but worker was on private property at request of owner—owner keeps. a. General Possession Theory—if property owner has possession of land and manifest interest to control it and all things on it then should also get all things on land—whether they know that they are there or not. 6. Hannah v. Peel—Army lance-corporal finds brooch in house where he was stationed—court distinguished this 1 from Sharman since the owner of house did not employ finder nor had he ever lived there. a. Minority view—should let owner of real property where object was found to keep the property because that is where the true owner is most likely to come back and look for it. 7. McAvoy v. Medina—customer finds wallet in barber shop on the counter. Court distinguished mislaid property from lost/abandoned property. Here the owner of real property has a bailment for the mislaid object and finder has no claim. 8. Schley v. Couch—buried money in garage is determined to be mislaid property rather than lost so the owner of real property has greatest claim to the property not the finder. Buried property should always belong to the property owner. If mislaid long enough then it may become ‘lost’. B. Bailments-- the relationship between the owner of chattel and one who possesses it lawfully. It is not a transfer of ownership, merely of possession. i. Requirements for Bailment— 1. Bailee must have knowledge of possession of chattel 2. May be an express or implied agreement a. Express—car rental b. Implied—clothes to laundry 3. Implied in Law— a. Constructive—party acquires possession through taking or fraud or finder of lost property is said to be a constructive bailee b. Involuntary—owner accidentally leaves property with another (who knows about it) ii. Rights of Bailee— 1. before delivery—no right to chattel before in bailee’s possession. However may have action for damages if it is not a gratuitous bailment. If gratuitous bailment then perhaps estoppel (induced reliance). 2. after delivery—bailee has exclusive control of bailment (so long as use within terms of bailment), has right of possession against all the world (including bailor) for term of bailment, can recover full value of chattel irrespective of liability to bailor if 3rd party damage. Has rights to profits from possession during term. 3. bailed objects are not subject to creditors of bailee—but can get right to use under bailment (unless expressly forbidden) 2 iii. Duties of Bailee— 1. general duty to exercise due care to protect and preserve the bailed goods. Not entitled to compensation for services but can get expenses for upkeep. 2. Liability—reasonable care. a. Absolute liability if deliver bailed chattel to someone other than the bailor—tort of conversion. iv. Bailment for hire—defined as a bailment for which the bailee is compensated, as when one leaves a car with a parking attendant.— v. Cases— 1. Allen v. Hyatt Regency Nashville Hotel—customer parks car in lot that has gated entry/exit and charges to park and the car is stolen. Court found that a bailment was created (bailment for hire)—presumption of negligence 2. Cowen v. Pressprich—bondsmen on Wall Street—wrong bond was given to broker who tried to return it to messenger but wrong messenger. Court found that no bailment existed—relied a lot on customary practices in the bond business. C. Bona Fide Purchase—a purchase in good faith for value without notice (of defects in title) i. In order to be a good faith purchaser you must buy from a dealer in goods of that kind. If someone entrusts an item of personal property with a dealer of goods in that kind then they are barred from recovery if they sell those goods (statutory estoppel). If you entrust something with someone that makes it look like it is theirs (reliance) then you can be estopped from recovery if they sell (equitable estoppel)—for common law or non-dealers 1. Porter v. Wertz—case dealt with both statutory and equitable estoppel. Painting loaned to someone who then sold it. Ruled that the seller was not a dealer in goods of that kind and the buyer (art dealer) was not a good faith purchaser (did not inquire as to origin of painting) so no statutory estoppel. Also, owner of painting had not bestowed all indices of ownership upon seller so no equitable estoppel either. Requires something more than possession. 2. Sheridan-Suzuki v. Caruso Auto Sales—When there is the general UCC statutory estoppel and a more particular statute, the more particular statute must be fulfilled in order for a party to be estopped. Bouton held a voidable title until the sale was completed (check cleared). D. Adverse Possession—someone takes another’s property and holds it: i. in an open and notorious way 3 ii. under a claim of right iii. for a certain time period then it becomes theirs and the original owner is estopped from recovery. iv. Cases— 1. Chapin v. Freedland—counters were installed in original building and then kept throughout ownership of building/years. If property belonging to another is held openly under a claim of right then the original owner must recover the property within the statute of limitations set by the court or they lose their right. 2. O’Keefe v. Snyder—O’Keefe’s painting were stolen (never reported) and they resurfaced much later. Because they were highly concealable (in people’s houses) the clock should not have started to run until she should have known (by exercising due diligence) where paintings were. a. Modification of Discovery Rule—the clock for adverse possession does not start to run until the rightful owner discovers or should have discovered the whereabouts of the item (and have been diligently seeking the items). This rule is designed to protect innocent owners from losing items just because they are highly concealable. E. Gifts—have three elements of intent, delivery, and acceptance. Acceptance is usually presumed unless the donee indicates otherwise. Gifts promised in the future are not valid under the law and not enforceable. i. Delivery of tangible gifts normally involves actually giving the person the object, unless the donee already has possession of the item or by giving a writing to represent the gift. Delivery of intangible gifts requires a symbol or token of the object or a written conveyance. 1. In re Cohn—husband gave wife stock (in form of letter saying what he had assigned) then died before stock was actually transferred. Wife owned stock. ii. Inter vivos gifts—gifts that are given during the lifetime of the donor to another. They are valid upon delivery of the gift. 1. Gruen v.Gruen—Father gave a painting to his son but kept possession until his death. Valid inter vivos gift even though father retained possession. iii. Causa mortis gifts—gifts given in contemplation of death. The gift must be delivered (become effective) during the donor’s lifetime. Causa mortis gifts are revocable by donor and do so automatically if donor recovers. 1. Foster v. Reiss—Woman tried to give husband property b/c of her impending death. She wrote it to be effective after 4 she died (if she should do so during surgery). Court found NOT valid b/c no delivery and testamentary in nature. 2. Scherer v. Hyland—Woman signed over settlement check to live in lover (and left other items) then committed suicide. Court ruled was a valid causa mortis gift since she left check on table for him to find and her death by suicide was clearly impending. However, other property was not his. iv. Conditional gifts—gifts given upon the receiver fulfilling a condition. Usually gifts are not conditional. 1. Lindh v. Surman—man gives woman diamond engagement ring, breaks off engagement, wants ring back. Court ruled that gift was conditional upon marriage and without that she had to return it (no fault rule). The other rules considered by the court were the fault rule—ring goes to whichever party was not at fault in breakup or the modified fault rule—if donor breaks the engagement then the donee keeps the ring no matter who was at fault. II. Real Property A. Freehold Estates i. In re O’Connor’s Estate—here the estate escheated back to the state. Since it was a reversion the state did not owe inheritance taxes on the property. ii. Fee Simple Absolute—estate that has infinite duration, is inheritable, devisable, alienable. In early times you had to include the words to A and heirs to create a fee simple. Now it is assumed unless you insert words indicating otherwise. 1. Cole v. Steinlauf—question was about the validity of title involved in sale. The original deed did not have the words “and heirs” so question was about whether or not it was alienable. Court found that it was marketable. 2. Intestate Succession—passes to the next of kin including the wife and children by various percentages depending on the statute. There are exceptions for illegitimate children— get inheritance of mother always and of father if he has ‘claimed’ the child. iii. Life Estates—estates measured by the term of a life, the life may be the recipient’s or some other measuring life. These estates are alienable but not devisable nor inheritable. 1. Lewis v. Searles—estate left to woman so long as she doesn’t marry. She didn’t marry and wanted to pass along the land in her will. Court found that she did not meet the condition to make it a life estate only thus it became a fee simple subject to divesture if she married. 5 2. Moore v. Phillips—Woman has life estate followed by remainder to daughter and her son. Life tenant allowed waste on the property and remaindermen could recover against her estate because of waste. Life tenants cannot waste land or allow waste to occur. If life tenants do commit waste then court can terminate the life estate and give it to the remainderman then. iv. Defeasible Estates—estates that have a condition that prompts a re-entry by the donor. They can be of two types: 1. Fee Simple Subject to Condition Subsequent—if event occurs then the landowner must make an effort to reclaim the land (does not happen automatically). Usually contains words such as “upon condition that”, “provided that” and comes with a right of reentry. 2. Fee Simple Determinable—if condition occurs then the land automatically reverts to the landowner without further action. Contain words like “so long as”, “until”, “during” followed by words of reverter which contains a possibility of reverter. 3. Oldfield v. Stoeco Homes, Inc.—here the question was what kind of estate was created (condition subsequent or determinable). The deed contained both types of language (automatic reverter in there) but the city did not come in and take possession. Court found it was condition subsequent (based on totality of document). v. Future Interests—estate which will or may become possessory at some future time. They are inheritable and most are also devisable and alienable. 1. Future interests in the grantor— a. Reversion b. Right of reentry (defeasible estates, determinable) c. Possibility of reverter (condition subsequent) 2. Future Interests in the grantee— a. Vested and Contingent Remainders—two types of remainders: i. vested—given to a born or ascertained person and not subject to a condition precedent 1. vested remainders can also be: a. indefeasibly vested—not subject to defeat b. vested subject to partial divestiture—class can 6 become larger and shares smaller c. vested subject to total divestiture—can be totally taken away by some act. ii. contingent—given to an unborn or unascertained person or subject to condition precedent. b. Executory interest—a future interest in a third party that divests or cuts short a prior estate 3. Cases— a. Kost v. Foster—Son had life estate followed by remainder to children or grandchildren (vested). Before death of life tenant, remainderman conveyed his portion of title away. Court held this was a valid conveyance b/c he was vested in the estate and his share was alienable. b. Abo Petroleum Corporation v. Amstutz—Sisters were given life estates with remainders to children or heirs—contingent remainders are alienable. Second deed gave them absolute title. Tried to convey title to petroleum company. Children argued that their interests were vested thus the land became theirs at life tenant’s deaths. Court agreed. Abo held so long as sisters were alive. The destructibility of contingent remainder doctrine is rejected here. 4. Doctrine of Destructibility of Contingent Remainders—O to A for life then to B’s heirs if B is alive when A dies (B’s heirs are unknown) the remainder fails and it goes back to O. If it is not destroyed then it remains with O until B dies then springs to B’s heirs. 5. Rule in Shelley’s Case—when a devise or conveyance transfers a freehold estate to a person and in the same instrument also transfers a remainder to that same person’s heirs or the heirs of his body, and both estates are either legal or equitable, both are considered to be held by the first-named freeholder, either for life, in fee simple absolute. Essentially, the rule picks up the contingent remainder and gives it to the life estate holder giving them the fee simple. This is a rule of law and not intent and is abolished in most states. O to A for life then to heirs is the same as O to A and heirs. a. Sybert v. Sybert—Man given a life estate with the remainder to the “heirs of his body”. Had no 7 children. Wife argues that Rule in Shelley’s case applies and she gets land by intestate succession. Brothers argue that it reverts and they get it. Court applies rule and wife gets estate. 6. Doctrine of Worthier Title—in form of O to A for life then to heirs of O. When there is an inter vivos conveyance to a person with a remainder or executory interest to the grantor’s own heirs, no future interest is created and it reverts to the grantor. Rule against remainder to grantor’s heirs. a. Braswell v. Braswell—the conveyance was of form O to A for life then to A’s lawful heirs, should A have no heirs then to O or O’s heirs. A did not have any lawful heirs but devised the property to a nephew. Since the heirs were determined at O’s death and not A’s death the nephew could get the land by his uncle’s devise of his share. The class was closed (all members vested) so A’s conveyance to nephew was valid either way. 7. Rule Against Perpetuities—the remainder must vest within 21 years of some life in being at the time of the grant or not at all. This does not apply to vested remainders but both contingent remainders and executory interests are subject to this rule. Look at the grant as it was written and see if you know when the interest will vest. If not then could have a perpetuities problem. a. The City of Klamath v. Bell—the grant of land was to the city so long as it was used as a library. It was used as a library for a number of years but ceased. Since did not satisfy rule the remainder failed and the land reverted back to the grantor (or their assigns in the stockholders of the company). vi. Concurrent Estates—when two or more people own the same piece of property at the same time (all names on the title). There are three types of concurrent ownership: 1. Tenancy in Common—two or more people holding land together. Their interests are alienable, devisable, and inheritable. Each tenant has a right to possession, nonequal shares are allowed, estates need not be same (life estate v. fees). This is the presumption to conveyances to people not husband and wife. 2. Joint Tenancy (with right of survivorship)—people holding land as joint tenants have alienable rights to land but no devisable or inheritable interests—because of right of survivorship. Must have four unities of title to be valid. 8 This requires the joint tenants to take at the same time, by the same instrument with identical interests and right to possession. If one of the unities is destroyed then the joint tenancy is severed and you get a tenancy in common. Can sever by alienating your share, mortgage of share in title theory states, murder of one of tenants. 3. Tenancy by the Entirety—is only for married couples. The interests are not alienable, devisable, nor inheritable. However it protects against creditors of one spouse or the other. 4. Cases: a. In re Estate of Michael—two married couples took title to farm land together (each couple owns undivided ½ of land). One husband dies, so his wife owns their entire share. She attempts to devise her half. PA law favored tenants in common so she could devise. b. Laura v. Christian—Four people owned land. Stopped paying so going to be sold at public auction. One paid entire payment. Two others got out. One wanted to pay his share to retain his portion of land. So one who paid owned ¾ and other owned ¼. c. Jackson v. O’Connell—Three sisters held property as joint tenants. One sister conveyed her share to other sister (thus destroying unity of title). This caused sister to own 1/3 as tenant in common with other sister and 1/3 as joint tenant. She then tried to devise all 2/3. Court ruled that she had 1/3 to devise and other 1/3 went to sister via right of survivorship. d. Palmer v. Flint—conveyed property to husband and wife as joint tenants w/r.o.s. Divorced and wife quitclaims deed to husband (severing the four unities). Husband has deed reconveyed to him and his sister (creating all four unities in the new deed). After husband dies, ex-wife comes back and says it is hers because of right of survivorship clause. However, sister gets it b/c has all four unities of title. e. People v. Nogarr—husband and wife got property together as joint tenants. They separate and husband mortgages his share of property to his parents. Husband dies and state wants to take land by eminent domain. Wife claims that mortgage was 9 simply a lien on his interest in the property and it disappeared at his death due to r.o.s. clause. i. There is a SPLIT in the mortgage between title theory states—serves to transfer a title or interest and lien theory states—creates a lien only on the share of the mortgagee. f. Mann v. Bradley—property held by husband and wife as joint tenants. Divorced and wife retained possession. Divorce action stipulated that the property was to be sold when one of conditions were met (wife remarries, youngest child reaches 21, mutual agreement of parties). Woman died and husband wanted entire property under r.o.s. clause. Court gave him undivided ½ interest with children as tenants in common. Because the divorce intended to create a tenancy in common no further destruction of four unities is needed. g. Duncan v. Vassaur—Property owned by husband and wife as joint tenants. Wife killed husband and conveyed property to her father under r.o.s. in joint tenancy. Court ruled that murder severed the joint tenancy and made them tenants in common, so wife owned undivided ½ and husband’s heirs owned other ½. i. Slayer statutes— ii. Simultaneous death act—split property if the order of death cannot be determined B. Non-Freehold Estates i. Leaseholds—similar to deed in that it conveys an interest in real property. Different because it also is a contract. A tenant can bring an action against a trespasser. Difference between commercial and residential leases. Tenant has covenant for quiet enjoyment that says that landlord can’t just bust in anytime. Three types of leases: 1. Tenancy for term (years)—lease has definite beginning and ending point. Expires without notice by either party. If longer than three years must be in writing in order to satisfy the Statute of Frauds. 2. Periodic Tenancy—tenancy runs from period to period (months, years). Continues to run unless one party terminates. Does not have to be in writing. Termination notice is usually equal to a period with a maximum of 6 months. 10 3. Tenancy at Will—lasts as long as either party wants it to last, ends immediately at notice of one party. Does not have to be in writing. 4. Cases: a. Brown v. Southall Realty Co.—Tenant was reserving rent but the lease was void because it violated the DC housing code. b. Adrian v.Robinowitz—commercial lease where there was a holdover tenant at beginning of lease. The court ruled that landlord must put tenant in both actual and legal possession at commencement of lease (English rule—Majority). The American rule says that landlord need only put in legal possession not actual. c. Commonwealth Building Corp v. Hirschfield— tenant intended to vacate and did not quite get stuff out of apartment. Removed by next day. Landlord wanted to renew for another year term and tried to charge tenant for entire year for 12 hour holdover. d. Richard Barton Enterprises v. Tsern—Commercial lease of two floors of building. Problems with freight elevator that prevents tenant from moving things upstairs. Two separate issues: covenant of tenant to pay rent and covenant of landlord to keep in repair. Rent abatement by 1/3 b/c couldn’t use top floor and landlord must fix elevator. i. Eviction can be actual or constructive— actual eviction relieves the tenant’s obligation to pay rent. Constructive eviction is something that causes tenant to leave even though not evicted. Partial eviction causes tenant to leave for a time (rent is abated for that time). e. Piggly Wiggly Southern v. Heard—commercial lease to grocery store with rent to be percentage of profits over $2 million. Grocery store bought out by another and shut down and kept empty to prevent competition. No stipulation in lease that must continue business so it was okay for them to do this. “going dark aggressively” f. Handler v. Horns—Leased 5 story building and equipped with fixtures to run a particular kind of business. After lease expired wanted to remove the fixtures. Could remove trade fixtures but not others if could do so without damage to property. 11 g. Walls v. Oxford Management Co.—woman was h. i. j. k. l. sexually assaulted on property where she was a tenant. Landlord has duty to protect tenants from defects in land but not from third party criminal activity (could have assumed duty by doing something). Foundation Development Corp. v. Loehmann’s Inc.—Loehmann’s had a 20 year lease and had to pay for a percentage of common area space. Loehmann’s was one day late on paying rent and landlord instituted suit. Ruled that breach was trivial and could not cancel lease. Edwards v. Habib—tenant was evicted because was reporting violations to housing authority. Court ruled in tenant’s favor to discourage retaliatory evictions. United States National Bank of Oregon v. Homeland, Inc—Homeland leased building but abandoned lease because couldn’t pay. Landlord got new tenant that also defaulted. Landlord wanted Homeland to pay for all term that was without rent. Landlords have duty to mitigate damages by trying to find another tenant. Jaber v. Miller—Jaber had original lease and then assigned it to Norber and Son who assigned it to Miller. Jaber had favorable lease so got payment above the rent. Fire destroyed building (Jaber had original fire clause but assignees didn’t know about it). Court ruled that extra money was consideration for assignment and was still due. i. Sublease—tenant becomes sublandlord. The subtenant cannot sue or be sued by original landlord because not in privity of estate. ii. Assignment—establishes privity of estate between original landlord and assignee. Assignee is liable for rent b/c steps into shoes of tenant. Original tenant still remains liable for rent because of contractual obligation to pay rent. Childs v. Warner Brothers Southern Theatres— property leased to someone who assigned lease to WB who assigned lease to Carolina Theaters. The assignment to Carolina Theaters was not approved by landlord so WB was still responsible for all rent 12 when Carolina defaulted (although landlord could have also sued original lessee). Dumpor’s rule did not apply here. i. Dumpor’s Rule—when lessor gives permission for assignment once then gives permission for all future assignments as well. Followed in most jurisdictions but rejected by restatement of property. m. 21 Merchants Row Corp. v. Merchants Row, Inc.— lease entered into with clause that could not assign nor sublet without express written consent of landlord. Wanted to assign but landlord refused. Landlord can refuse permission without giving a reason. Minority rule that landlord must have reasonable reason. C. Interests in Land of Another i. Easements 1. Affirmative easements—easement owner has right to go onto property of another and do acts. 2. Negative easement—owner of easement may prevent property owner from doing acts that could otherwise do a. Appurtenant—runs with the land b. In Gross—benefits easement holder without regard to land (no dominant estate) 3. Licenses—privilege to go onto land and do acts, is revocable at will of licensor. Licensee is not protected from interference by third parties. 4. Express Consent a. Mitchell v. Castellaw—woman owned three lots and conveyed away part of it and tried to reserve an easement to herself. The easement was appurtenant to the land and was not personal. Normally cannot convey away land and reserve easement to self. b. Willard v. First Church of Christ, Scientist, Pacifica—woman agreed to deed away property if an easement was reserved for the church to park on Sunday mornings. Normally cannot reserve an easement to a third party but she testified that this was what she wanted, so they gave church the easement. c. Urbaitis v. Commonwealth Edison—grant to railroad for bed. Is now abandoned. Railroad wants to give it for rails to trails project, adjacent landowner says it was an easement and is now 13 theirs. Court holds that it was a conveyance because of words “convey and warrant” in deed. d. Baseball Publishing Co. v. Burton—Building owner granted right to advertiser to place a sign on the side of his building for one year at $25 (w/option to renew). Advertiser sent money for three years (always refused). The building owner took sign down without notice. Language of ‘exclusive rights’ implied easement in gross for term of years so landlord couldn’t take down (could have if it were a license) e. Stoner v. Zuker—original license granted and licensee came in and erected a complex water delivery system. Man then wanted to revoke license after money spent. Court held that license had become irrevocable and owner was estopped from revoking it because induced reliance. 5. By Implication a. Finn v. Williams—owner conveyed away a landlocked parcel with no access to roads. At first had access over others property but now closed. Court held that easement always existed over larger parcel by implication—always an easement when parcel landlocked—easement by necessity. b. Granite Properties Limited Partnerships v. Manns— property owner originally owned all parcels in area. Used parts for driveway before conveyed to someone else—use was obvious. Court held that easements existed by prior use. 6. By Prescription a. Beebe v. DeMarco—interior property owner in neighborhood drove across back portion of neighbor’s lot to access street. Had done so for over 10 years before owners objected. Held that acquired easement by prescription. 7. Scope—usual remedy is injunction—rarely does violation of easement use operate to extinguish the easement. a. S.S. Kresge Co. v. Winkelman Realty Co.—had easement granted for ingress and egress into property but defendant began to use for other purposes. Court held that non-approved uses must stop but could still use easement for ingress/egress. b. Sakansky v.Wein—had easement and owners of servient estate wanted to either move easement or cut headroom to only 8 feet. Reasonableness 14 standard for allowing change. Here must leave more than 8 feet or build elsewhere. i. Restatement—burdened estate may change if equal utility however owner of easement may not change the easement location. 8. Termination—ways to terminate— a. By estoppel b. By prescription c. By a good faith purchaser d. By merger with servient estate e. Necessity ends f. Consent of both parties g. Cases— i. Lindsey v. Clark—confusion as to where easement was (north or south). Wanted north easement terminated b/c easement was reserved on south and south terminated because of of lack of use. Cannot abandon easement unless expressly say so. ii. Real Covenants and Equitable Servitudes 1. Real Covenants—must have intent to bind successors, touch and concern the land, and have privity of estate (either vertical or horizontal)—may get monetary damages or injunction 2. Equitable Servitudes—must have intent, must touch and concern the land, owner must have notice—injunctive relief only 3. Cases: a. Neponsit Property Owners Ass’n. v. Emigrant Industrial Sav. Bank—there was a covenant for the property to pay fees for a certain number of years. The covenant ran with the land and was not personal to the prior owner. Thus all other owners in the chain of title must also pay the fees. b. Tulk v. Moxhay—property contained a covenant (equitable servitude) that a statue in the park would be maintained (not in deed but parties had notice). Someone wanted to build something else on property. Owner of covenant wanted injunction. This case substituted notice for privity of estate. c. Sprague v. Kimball—property owner owned several lots. Sold lots 1-4 with restrictions on where and what could be built on the land. Sold back part of 5th lot without restrictions. Was an equitable 15 d. e. f. g. servitude but not in writing so could be sold without restriction. Must be in writing, cannot be oral promise. Exceptions include estoppel and part performance. Sanborn v. McLean—owner of lot in a subdivision tried to build a gas station on the back portion of the lot. Neighbors argued that there was a negative reciprocal easement on the property b/c of plan for neighborhood. Cannot build commercial property on land zoned for residential purposes— constructive notice. Cowling v. Colligan—landowner in development wants to sell land for commercial use. Is on edge of development. Argues that they are estopped because allowed churches to be built in development. Court found this did not estop and didn’t matter what was happening outside of the development. Waldrop v. Town of Brevard—town had land used for town dump. Contained a covenant not to sue. Landowners around wanted it declared a nuisance and the change in the character of the surrounding land warranted it to be removed. Determined that the covenant bound all the other landowners as well because they all arose from the same grantor. This was really an easement in the guarantee not to sue or interfere with operation of the dump. Ways to get rid of covenant— i. Abandonment by owner ii. Acquiescence iii. Estoppel iv. Relative hardship v. Changed conditions (within restricted properties) iii. Natural Interests 1. Noone v. Price—two houses built on hill. Lower landowner had retaining wall that had deteriorated and upper landowner’s house was sliding down hill. Landowner has duty to support upper land if take away natural support (strict liability); also duty to support structures if already there (negligence). No duty to support house here since it was not there when original excavation took place. 2. United States v. Causby—US landed planes close to land so that it was useless. Landowner brought inverse 16 condemnation action to get payment. Property does not extend all way up to sky but here the interest of land had been invaded so US had taken easement. 3. Edwards v. Sims—man had excavated and explored cave that possibly ran under other’s land. Court ruled that landowner owned all the way to the center of the earth and if the cave ran under their land then they owned it. Strong dissent in this case that the result was inequitable and absurd (can’t own to center of earth). III. Real Estate Contracts A. Oral Contract—generally can have leases for less than three years without putting them in writing. However, the option to buy must always be in writing. i. Shaughnessy v. Eidsmo—agreed to oral lease with option to buy on house and stove (probably a fixture). Made monthly payments. At end of year notified owner that wanted to exercise option to buy and asked for contract. Owner claimed too busy to do so and then filed suit. Court ruled that plaintiffs had performed their part of bargain and thus owner could not go back on option to buy. ii. Part performance—equitable doctrine that can force specific enforcement or oral contract. Look to what has been done to determine contract’s intent. B. Written Contract i. Skendzel v. Marshall—installment contract to buy land. Buyer had made some payments ahead and behind and seller had accepted. Missed a payment after paying over half of the purchase price. Seller wanted default of contract, return of land, liquidated damages (court decided it was penalty). They were estopped because they had accepted late payments before and it would be unfair to forfeit all of land when had paid for more than half. Turned installment into mortgage where would have to go through foreclosure to get land (more favorable to buyer). ii. Wallach v. Riverside Bank—contract for sale of land stipulated quitclaim deed. Buyer discovered that there was a dower outstanding on land and refused to take deed. There is a presumption for a clear title (warranty deed) at sale so buyer does not have to accept defective deed (unless defect is stipulated in contract and accepted by buyer). iii. Bleckley v. Langston—contract for sale of land that contained pecan trees. Between signing of contract and actual sale an ice storm destroyed most of trees. Two rules at play: England rule— the buyer accepts losses between contract and closing. Massachusetts rule—the seller accepts losses (later adopted in England but minority rule in US). Determined that if vendor has 17 IV. performed his part of contract and can convey title then losses fall on the vendee (equitable title doctrine). Here buyer bears loss. 1. North Carolina statute—Uniform Vendor and Purchaser Risk Act—when neither legal title nor possession of land has passed the seller bears loss. When either legal title or possession has passed to buyer they bear the loss. The Deed—warranty deeds and quitclaim deeds—warranty usually used in real estate transactions—promises clear title. Warranties—warranty of seisin, warranty of good right to convey, warranty against encumbrances, covenant of warranty A. Execution of Deed i. Clevenger v. Moore—woman may sell building and gives deed to escrow agent. Leaves town, escrow agent gives to potential buyer (without permission of seller) who then sells land to GFP. Woman wants land back. If deed was stolen then it is void. If Clevenger created situation by leaving signed deed with escrow agent then could argue estoppel (b/c of inducement and reliance). To deliver a deed it must be signed and delivered (just like a gift). B. Recording System i. Types of recording systems: 1. Tract system—deeds are arranged by tract number—easier to search, used primarily out west. 2. Grantor-Grantee system—deeds are listed in two indexes— one by grantor and one by grantee (some also have tract numbers) ii. Title Searching: 1. Develop a chain of title—search the grantee index to determine the chain of title 2. Look for adverse conveyances—in grantor index determine if any easement, etc. has been granted away in the history. 3. Read each deed—to look for problems or irregularities iii. Cases: 1. Mountain States Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Kelton— property owners were doing construction on land and did not notify contractors of underground telephone wires. They began to dig and damaged the wires. The wires were not obvious and contractor was under no obligation to search title to find their whereabouts (however landowner was). Usually only buyers, lenders are required to search titles. Irrebuttable presumption that those with interest in land has notice of what is in the record. 2. Mugaas v. Smith—woman had obtained title to strip of land by adverse possession. She had ceased to use it and buyer of property had no way to know about the title since 18 it was not in the chain of title. She did tell them to stop building but they ignored. She could not lose title by disuse and still held even though not recorded. iv. Types of Recording Statutes: 1. Pure Race—first person to recording office with deed gets the land. Notice is not part of the requirement (can know there are two deeds outstanding)—NC has this type. 2. Race-Notice—first person (without notice) to buy property and get to the recording office first gets title to the land. 3. Pure Notice—if a bona fide purchaser without notice pays for the land then they get it—no matter who records first. a. Mortensen v. Lingo—property conveyed to buyer who tried to record deed but not indexed. Property then conveyed to different buyer who recorded the deed then sold to another person (all under warranty deeds). First conveyee tried to evict current tenant. They sue their seller for breach of warranty. Held that subsequent buyer got land because prior conveyance was not in record (race-notice statute) b. Simmons v. Stum—property conveyed subject to mortgage then subsequently conveyed without notice of mortgage. The mortgage was recorded before the deed thus she was on notice of mortgage and was responsible for it. (race-notice statute). c. Eastwood v. Shedd—Woman deeded land to someone (who did not record) then deeded to her daughter as a gift (did record). The statute in Colorado does not limit protection to GFP but to all having an interest in property. Court ruled that CO statute was race-notice so the daughter kept the land. C. Title Assurance i. Implied covenants of habitability—used to only be for older houses but trend is to new houses built by builders. 1. Petersen v. Hubschman—people entered contract with builder to build house and paid earnest money deposit and also contributed building materials. House had some defects (not inhabitable) but buyers refused to take deed. Court ruled that the defects here were included in warrant of habitability (up to standards of construction). ii. Adverse possession—if owner of land does not take action to oust adverse possessor within the statute of limitation period then cannot assert title and it passes to adverse possessor. 1. Requirements— a. Open and notorious 19 b. Adverse and under a claim of right c. Continuous for statutory period 2. Howard v. Kunto—owners of summer homes in a row along canal had been living on wrong property for years (one lot off). Ruled that current owners could tack prior owners possession onto their time to reach the statutory time. Works only if the owners were in privity. 20