Get - Wiley Online Library

advertisement

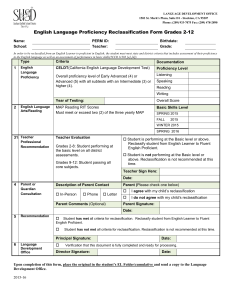

Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 33(7) & (8), 1189–1212, September/October 2006, 0306-686X doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5957X.2006.00593.x Debt Reclassification and Capital Market Consequences Jeffrey D. Gramlich, William J. Mayew and Mary Lea McAnally∗ Abstract: We provide initial evidence on the economic consequences of a relatively large, fully disclosed, and apparently purposeful reporting decision: the balance sheet classification of shortterm obligations as long-term debt in accordance with Statement of Financial Accounting Standard No. 6. We examine a sample of 1,684 American firm-year observations between the years 1989 and 2000 to determine whether reclassification is associated with debt-ratings and equity values. We find that reclassification increases the likelihood of a subsequent debt-rating downgrade. We also find that market value decreases with increases in the amount reclassified, and that equity value is higher after firms cease reclassifying short-term obligations as long-term debt, compared with other firm-years in the sample. Thus, changes in debt classification are empirically linked in predictable directions to subsequent changes in debt ratings and stock values. Taken together, our results show that debt classification is an important publicly-available indicator that may be useful to capital market participants. We discuss several research extensions including the implications of our findings to European companies that convert to IAS in 2005. Keywords: debt classification, economic consequences, debt ratings, market value of equity 1. INTRODUCTION This paper provides initial evidence on the economic relevance and consequences of a large, fully disclosed, and apparently purposeful reporting decision: the balance sheet classification of short-term obligations as long-term debt in accordance with Statement of Financial Accounting Standard No. 6 (SFAS 6). Gramlich, McAnally and Thomas (2001), (hereafter GMT) document that firms use the flexibility afforded by SFAS 6 to smooth key liquidity and leverage ratios toward both industry benchmarks and prior-year levels. GMT demonstrate that firms shift short-term debt to the long-term category (i.e., ‘reclassify’) in some years while in other years these ∗ The authors are respectively, from the University of Southern Maine and Copenhagen Business School; the University of Texas at Austin; and Texas A&M University. This paper has benefited significantly from the comments of Shane Dikolli, Michelle Hanlon, Karim Jamal, Ross Jennings, Bill Kinney, Lisa Koonce, Tom Scott, Senyo Tse and Connie Weaver as well as from workshop participants at the University of Alberta and the 2002 University of Texas at Dallas Accounting and Finance Symposium. (Paper received January 2005, revised version accepted July 2005. Online publication April 2006) Address for correspondence: Mary Lea McAnally, Accounting Department, Mays Business School, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA. e-mail: MMcAnally@mays.tamu.edu C 2006 The Authors C 2006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK Journal compilation and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA. 1189 1190 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY firms move such debt back to the current category (i.e., ‘declassify’). These classification changes reduce the variability of firms’ current and long-term debt ratios across time and mitigate the deviation of liquidity ratios from industry norms. We extend GMT by directly addressing the economic relevance of debt classification. In particular, we contend that debt classification is not an innocuous financial reporting decision—managers do not accidentally reclassify debt—and some of the motivation is apparently driven by the desire to portray the firm as healthier than it actually is. We provide empirical evidence economically linking firms’ debt classification decisions to stakeholder wealth. SFAS 6 permits a firm to reclassify short-term debt as long-term if a loan commitment is obtained that extends for more than a year beyond the balance sheet date. Our data reveal that each year from 1989 to 2000, about $26.7 billion of commercial paper (which the SEC defines as short-term) is classified as long-term debt. This averages $564 million per firm each year during our sample period. The disclosure in Exhibit 1 typifies SFAS 6 debt reclassification. Firms must exclude short-term obligations from current liabilities if the firm (1) intends to replace the maturing short-term debt issue with another issue; and (2) has the ability to do so. 1 Firms demonstrate ‘ability’ with credit-facility terms that extend beyond the term necessary to support the short-term obligation. While the standard states that firms ‘shall’ reclassify, in practice, considerable discretion remains. To exercise discretion a firm can either declare that it has no intent to replace the current debt issue or fail to secure appropriate enabling credit facilities. Ceteris paribus, long-term credit facilities are more costly than short-term facilities; thus, firms incur real costs to enable reclassification. Sound economic reasons may exist for firms to obtain longer-term loan commitments, such as less costly commercial paper rollovers and longer-term invested capital. However, we consider the possibility that some firms strategically reclassify and declassify debt and that these strategy decisions impact stakeholder wealth. To substantiate our claim that debt reclassification is not an innocuous financialreporting choice, we first develop and estimate a model that explains reclassifications. The evidence indicates that firms with lower leverage, current ratio, and operating cash flows more frequently reclassify short-term debt as long-term. This suggests that managers reclassify to obscure the firm’s true financial condition and not to simply reveal the likely timing of debt repayments. We also assess whether changes in classification systematically predict differences in the costs of debt and equity capital. Although other research ties earnings properties to shareholder wealth (e.g., Kormendi and Lipe, 1987; Ohlson, 1995; Sloan, 1996; and Barth, Beaver et al., 1999), we examine whether balance sheet debt reclassification is associated with subsequent changes in debt ratings. After controlling for demographic and financial variables known to influence debt ratings, firms that reclassify are more likely to experience a debt-rating 1 ‘A short-term obligation . . . shall be excluded from current liabilities only if 1) the enterprise intends to refinance the obligation on a long-term basis and 2) the enterprise’s intent to refinance the shortterm obligation on a long-term basis is supported by an ability to consummate the refinancing (which is) demonstrated . . . by a financing agreement that clearly permits the enterprise to refinance the short-term obligation on a long-term basis on terms that are readily determinable and . . . the agreement does not expire within one year . . . and during that period the agreement is not cancelable by the lender or . . . investor.’ (Financial Accounting Standards Board 1975, Statement 6, paragraphs 9–11). C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES 1191 Exhibit 1 Excerpt from the Debt Footnote of Pacificorp’s 1998 Form 10-K The Company’s long-term debt was as follows: (in $millions) PACIFICORP 12/31/98 12/31/97 First mortgage and collateral trust bonds Maturing 1999 through 2003/5.9%–9.5% $ 816.4 $ 1,005.6 Maturing 2004 through 2008/5.7%–7.9% 1,032.7 632.7 Maturing 2009 through 2013/7%–9.2% 328.6 331.6 Maturing 2014 through 2018/8.3%–8.7% 98.4 100.9 Maturing 2019 through 2023/6.5%–8.5% 341.5 341.5 Maturing 2024 through 2026/6.7%–8.6% 120.0 120.0 Guaranty of pollution control revenue bonds 5.6%–5.7% due 2021 through 2023 (a)71 71.2 71.2 Variable rate due 2009 through 2013 (a) (b) 40.7 40.7 Variable rate due 2014 through 2024 (a) (b) 175.8 175.8 Variable rate due 2005 through 2030 (b) 450.7 450.7 Funds held by trustees (7.4) (9.1) 8.4%–8.6% Junior subordinated debentures due 175.8 175.8 2025 through 2035 Commercial paper (b) (d) 116.8 120.6 Other 21.9 25.1 Total 3,783.1 3,583.1 Less current maturities 297.6 194.9 Total 3,485.5 3,388.2 SUBSIDIARIES 6.1%–12.0% Notes due through 2020 649.8 264.5 Australian bank bill borrowings and commercial paper (c) (d) 414.3 756.6 Variable rate notes due through 2000 (b) 11.6 12.1 4.5%–11% Non-recourse debt – 160.7 Other – 1.4 Total 1,075.7 1,195.3 Less current maturities 1.9 170.5 Total 1,073.8 1,024.8 TOTAL PACIFICORP AND SUBSIDIARIES $4,559.3 $4,413.0 Footnotes (a) through (c) excerpted. (d) The Companies have the ability to support short-term borrowings and current debt being refinanced on a long-term basis through revolving lines of credit and, therefore, based upon management’s intent, have classified $531 million of short-term debt as long-term debt. downgrade relative to firms that do not reclassify. But we find no evidence that declassifying firms are more likely to experience a debt-rating upgrade. We do, however, find that the market value of equity decreases when firms begin reclassifying and increases when firms cease reclassifying. Taken together, our findings suggest that capital-market participants view reclassification as a ‘red flag’ indicative of management intervention in the reporting process. Our debt-rating and market-value results potentially provide firm managers with a better understanding of the economic consequences of their reclassification decisions. Additionally, our findings provide evidence concerning an accounting choice that influences debt-covenant compliance. Firms and lenders could use these findings to structure debt covenants that either explicitly allow or disallow the reclassified amount C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1192 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY in computing covenant levels or ratios (see also Beatty, Ramesh and Weber, 2002). Thus, our research responds to the call by Fields et al. (2001), for studies ‘on whether the alleged attempts to manage financial disclosures by self-interested managers are successful’ (p. 258). The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 develops three hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data and our models. Section 4 discusses the results and Section 5 concludes and offers several research extensions. 2. HYPOTHESES (i) Factors Associated with Debt Reclassification Our first model explains debt reclassification. While reclassification does not affect a firm’s total liabilities, it simultaneously increases both the current ratio and the longterm debt ratio. Firms may reclassify because they believe that external parties monitor firm liquidity via the current ratio, for example. These parties could include equity analysts who appraise firms’ ability to meet obligations, lenders who set and enforce debt covenants or suppliers and others who use credit scores such as Altman’s Z -score, in making credit decisions. 2 Directly testing whether firms’ current ratios affect these parties’ decisions is difficult: most credit-scoring systems are proprietary and typical debt-covenant footnotes contain only boilerplate language. 3 Thus, to build our model, we consider that credit-scoring models and debt covenants typically specify minimum levels for current ratio or working capital measures (Altman, 2000; and Mester, 1997). This implies that firms with lower current ratios or working capital are potentially more likely to reclassify. Conversely, credit-scoring models and debt covenants typically specify maximum levels for total leverage or long-term debt. While reclassification improves liquidity measured by the current ratio, it increases leverage measured by long-term debt ratios. Consequently, we expect only firms with long-term debt slack to reclassify short-term debt to long-term. That is, reclassification may only be viewed as a viable alternative for firms to meet a liquidity target if it does not impact a leverage constraint. If firms reclassify to disguise worsening financial condition, performance measures such as operating cash flow and profitability would be negatively related to the reclassification decision. Thus, we predict: H1: Firms with lower current ratios, lower long-term debt leverage, lower operating cash flows and lower profitability are more likely to classify short-term obligations as long-term debt. 2 Mester (1997) reports that 70 percent of banks use multivariate credit-scoring models to make commercial lending decisions. 3 We searched Dealscan, Loan Pricing Corporation’s commercially available database of lending agreements with over 100,000 transactions on global loans, high-yield bond, and private placements since 1986. Dealscan summarizes specific loan information, including borrower, lender, amount, term, debt covenant data and sinking fund requirements. Although the December 29, 1999, version contains 1,355 lending deals with current ratio covenants, only 20 of these, representing only nine unique firms, were among our reclassifiers. Consequently, with the small sample size, we could not use the Dealscan data to statistically test potential debt-covenant violation hypotheses. C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES 1193 (ii) Economic Consequences of Reclassification Innocuous debt classification decisions would have no market consequences. On the other hand, if debt classification imparts useful information to debt and equity markets, capital-market activity may reveal these stakeholders’ views of forecasted future cash flows. By testing for capital-market responses to debt classification, we ascertain whether debt classification systematically predicts real economic effects to stakeholders. Specifically, we examine the impact of reclassification and declassification on debt ratings and on the market value of equity. (iii) Reclassification and Debt Ratings Debt-rating agencies such as S&P, Moody’s, Fitch Investors Service, and Duff and Phelps glean private information in evaluating firms’ credit worthiness. 4 Prior research establishes that credit analysts have economic incentives to reveal their private information (Millon and Thakor, 1985). We argue that debt-rating agencies may privately learn firms’ rationale for reclassifying and factor that information into their debt ratings. We consider two possible links from private information to debt ratings, one direct link and the other indirect. First, from detailed knowledge of the terms of existing debt agreements, debt raters may discern whether a firm reclassified short-term debt to avoid violating a debt covenant. This knowledge could directly affect a firm’s debt rating because debt-covenant violation has the potential to impact cash flows. Second, debt raters may ascertain that reclassification is related to other economic or managerial factors that affect firms’ credit ratings. 5 This knowledge could indirectly affect a firm’s debt rating. We consider both links below. Debt-covenant information is more-readily available to credit analysts than to financial statement readers. For example, consider the Pacificorp reclassification presented in Exhibit 1. Dealscan reports that a 1998 debt covenant required that Pacificorp Inc. maintain a current ratio of at least 1.1 to 1. This covenant was not explicitly reported in the company’s financial statements that year, although presumably debt raters access the same information used to develop the Dealscan database. In 1998, Pacificorp reclassified $531 million of commercial paper from current liabilities to long-term debt. The effect of this reclassification was to increase the company’s 1998 current ratio from 0.827 to 1.105 – just above the 1.1 level needed to avoid a covenant violation. Our conversations with several partners at public accounting firms confirmed that they would recommend reclassification to clients 4 Cantwell (1998) reports that annual meetings with the rating agencies are the norm and that 30 percent of survey respondents reported meeting with the agencies more than twice a year. Trade publications report corroborative anecdotal evidence, ‘Larger companies are usually visited annually by Moody’s personnel with supplemental visits by management to New York. We often arrange visits to the operations of individual business segments to assess specialized areas firsthand’ (Harold H. Goldberg of Moody’s Investors Service, quoted in Credit, 1991). 5 Picker (1991) reports the following example of rating agencies acquiring private information. In February 1991, AA-rated Shell Canada provided its rating agency with ‘advance insider information: Shell Canada’s decision to exit the coal business. The (rating) agencies approved of this material change in operations. And before the press release announcing the sale of the business went out in June, along with a resulting $120 million loss in earnings, (Shell Canada CEO) Darou’s staff phoned Moody’s, S&P and the two domestic Canadian agencies. . . . The analysts never blinked; Shell Canada was not downgraded at the time, nor was it put on a dreaded credit watch’ (Picker 1991, p. 76). C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1194 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY facing debt-covenant violations. The propensity to heed such advice may signal management’s broader predilection to intervene in the reporting process. Debt-raters also have access to private information gleaned in private discussions with management, detailed supplementary financial information, and on-site visits (Butler and Rodgers, 2002). This private information pertains to management’s depth, expertise, and historical track record, as well as to management’s strategies and overall philosophies. To the extent that reclassification is associated with this private information, debt ratings will be associated with reclassification. Although we do not posit that reclassification is a direct determinant of firm’s credit ratings, we argue that reclassification serves as a proxy for credit analysts’ private information, including insight into debt covenant proximity, economic conditions and management’s financial reporting strategies. In other words, debt reclassification signals firm weakness that debt raters can directly assess using private information. Thus, our second hypothesis is: H2: Debt ratings are negatively (positively) related to the reclassification (declassification) of short-term obligations as long-term debt. (iv) Reclassification and the Market Value of Equity There are cash-flow consequences to reclassification because the cost of a 366-day loan commitment exceeds the cost of a 90-day commitment. However, in most cases these costs are not likely to be large enough to have a statistically measurable impact on firm value. Apart from the loan-commitment fee, reclassification does not directly affect earnings nor does it appear to impact firm value. Nonetheless, as discussed above, we maintain that reclassification is a value-relevant signal. Consistent with prior research, we cannot specify the mechanism by which managers’ choice to reclassify current liabilities as long-term debt affects firm value (Fields, Lys and Vincent, 2001). Instead, we posit that a confluence of factors impact stock price (for similar hypotheses, see Kliger and Sarig, 2000; and Dichev and Piotroski, 2001). Thus we hypothesize: H3: The market value of firms’ equity is negatively (positively) related to the reclassification (declassification) of short-term obligations as long-term debt. 3. DATA AND MODELS (i) Sample Selection and Data Using Lexis/Nexus, we searched for firms that reclassified short-term debt during the period 1989 to 2000. 6 If a firm met the search criteria at any time within the 12-year period, we collected short and long-term debt footnotes for that firm for the complete period 1988 to 2000. 7 This approach identified a total of 3,080 firm-years. We gathered additional financial variables, debt ratings, and equity values from the Compustat and 6 Our Lexis/Nexus search term specified the word ‘reclass’ within 200 words of the term ‘commercial paper’ in firms’ annual reports of Forms 10K. The term is conservative in that it did not identify firms that did not mention commercial paper. 7 Because certain variables require lagged data, we also gathered data for 1988. C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1195 DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES CRSP databases. Missing Compustat data and insufficient current-year and prior-year footnote disclosures reduced our sample as indicated in Table 1, Panel A. The final sample is 1,684 firm-year observations between the years 1989 and 2000. Table 1 Sample Selection Panel A: Criteria for Sample of Firm-years that Reclassified at Least Once Between 1989 and 2000 Firm-years between 1989 and 2000 identified with search terma Less: Firm-years not available on Compustat Firm-years missing relevant Compustat and/or CRSP variables Firm-years missing sufficient current debt footnote information Firm-years missing sufficient prior-year debt footnote information 3,080 (462) (465) (346) (123) Final sample 1,684 Panel B: Industry Affiliation for Samples Resulting From Each Criteria 2-digit Reclassifying Non-reclassifying Industry Group † SIC Codes Firm-Years Firm Years Clothing Financial Food Media Metallurgy Miscellaneous manufacturing Oil Retail sales Services and other Transport Utilities Wood products Healthcare 22–23 60–69 1–7,20–21 27,48 34 39 13,46 50–59 70–79,83,99 40–45,47 49 24–26 80 Totals Panel C: Sample Distribution Across Years Reclassifying Year Firm-years Total Sample 5 35 52 361 40 0 72 104 62 47 56 86 12 24 28 62 231 23 7 17 94 55 21 74 56 0 29 63 114 652 63 7 89 198 117 68 130 142 12 932 752 1,684 Non-reclassifying Firm-years Total Sample 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 49 53 47 48 62 63 87 104 111 113 103 92 35 31 37 36 73 103 86 82 71 67 67 64 84 84 84 84 136 166 173 186 182 180 170 156 Totals 932 752 1,684 C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1196 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY Table 1(Continued) Notes: The table reports sample selection results. We applied the following search term to the AR group file within the NAARS library of Lexis/Nexus for the years 1989 through 1994: ((DATE = 1989) AND (COMMERCIAL PAPER W/200 (CLASSIF! W/25 (LONG-TERM OR NONCURRENT)) AND (COMMERCIAL PAPER W/200 (DUE W/10 1990)))). From 1995 through 2000, we applied the term to the COMPNY group file within the COMPNY library. We modified the search term accordingly for each of the subsequent 10 years. Once we identified a firm as meeting the search term at any point within the 1989–2000 period, we collected that firm’s financial data for all years between 1989 and 2000, producing 3,080 firm-year observations. The final sample contains only firms that reclassify short-term debt to long-term at some point during the 1989 to 2000 period and report sufficient financial and market data for the analyses. † Our search term did not identify any debt reclassifications in the following industry sectors: automobiles (37), chemicals (28–29), consumer goods (15–16), electrical (36,38), equipment (35), healthcare (80,82), material (32–33), mining (10,14), or professional service (87). We read and coded debt footnotes to obtain reclassification information, including the amount and type of short-term debt reclassified along with information pertaining to the terms of supporting loan commitments, interest rates, fees and compensating balances. We also searched the disclosures for information about debt covenants and any violations thereof. 8 We coded a firm-year as a reclassification if commercial paper, notes, or other debt maturing within the next year were classified as long-term pursuant to the ‘intent and ability’ paragraph of SFAS 6. (ii) Models We first attempt to explain firms’ decisions to reclassify and then we test for an association between reclassification (and declassification), debt ratings, and market value of equity. That is, we estimate pooled, cross-sectional time-series models using nonreclassification firm-years as a control for reclassification firm-years. In later sensitivity analysis, we match reclassification firms with firms that exhibit no reclassification activity at any point during the 1989–2000 period. The results we find with this matched sample are substantively the same as our main results. (iii) Factors that Explain the Decision to Reclassify The following logistical regression model evaluates factors related to firms’ decisions to reclassify: RECLASSi, t = β0 + β1 ROAi, t + β2 LEVi, t + β3 CRATIOi, t + β4 CFOi, t + β5 RECLASSi, t−1 + υi, t (1) where RECLASS i,t is a binary variable indicating one if firm i reclassified short-term debt as long-term in year t, and zero otherwise; ROA is earnings before extraordinary items scaled by total assets; LEV is the ratio of long-term debt to assets; CRATIO is 8 We examined the Dealscan database to obtain additional information related to working capital and current ratio covenants, since such ratios are directly impacted by reclassification. Dealscan, however, provided limited details regarding these covenants by our sample firms. C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES 1197 current assets divided by current liabilities; CFO is cash flow from operations scaled by total assets; and is the unexplained residual. Both CRATIO and LEV are calculated after adjusting for reclassification. Lev (1969) reports that firms’ financial ratios adjust toward the previous year’s industry averages. Among the six financial ratios Lev examines, the quick and current ratios exhibit the fastest and most significant adjustments toward industry averages. 9 Thus, it is plausible that firms reclassify to avoid deviation from industry benchmarks for certain key metrics. To address this in our examination of hypothesis 1, we control for industry norms by subtracting the annual industry median from each of our continuous independent variables, as follows: RECLASSi, t = β0 + β1 (ROAi, t − MedianROAi, t ) + β2 (LEVi, t − MedianLEVi, t ) + β3 (CRATIOi, t − MedianCRATIOi, t ) + β4 (CFOi, t − MedianCFOi, t ) + β5 RECLASSi, t−1 + υi, t . (2) We compute industry medians for two-digit SIC codes using data from the entire Compustat database for each year. Other variables are as previously defined. (iv) Models of the Association Between Reclassification and Debt Ratings We test for an association between reclassification and debt-ratings using a logistic regression of the direction of debt-ratings changes. 10 Our model includes demographic and financial variables suggested by Ziebart and Reiter (1992). We read Standard and Poor’s ‘Corporate Ratings Criteria’ (Standard and Poor’s 2001) to determine additional factors that credit analysts deem relevant. Thus, the model includes a parsimonious set of control variables suggested by theory and practice to test hypothesis 2. RATINGΔi, t0+1 = β0 + β1 + β2 ROAΔi, t + β3 LEVΔi, t + β4 CRATIOΔi, t + β5 CFOΔi, t 19 + β6 SIZEΔi, t + β7 RECLAMTΔi, t + β j INDi + υi, t j =8 (3) where RATING is the S&P discrete numeric senior-debt rating that ranges from 2, corresponding to a ‘AAA’ rating, to 27, corresponding to a ‘D’ rating. 11 We define RATINGΔ as ‘1’ if the firm’s debt rating improves (upgrades), as ‘-1’ if the firm’s rating deteriorates (downgrades); and as ‘0’ if the rating does not change. Thus, RATINGΔ i,t0+1 , captures the cumulative directional change in RATING i , across the 9 Lev (1969) does not explain how the ratio adjustments are performed, just that they occur, noting that, ‘. . . the techniques by which firms adjust their ratios were not investigated. This is a very complex problem since ratio adjustment may be achieved in several ways. . . . there is no way to identify specific techniques which probably differ from firm to firm’ (Lev 1969, p. 298). We hypothesize that reclassification may be one such technique. 10 See Ederington (1985), for a review of this empirical approach. 11 We explored S&P commercial paper ratings as an alternate dependent measure. However, fewer firms have commercial paper ratings and commercial paper ratings have fewer distinct ratings levels (7 possible ratings for commercial paper compared to 27 possible ratings for long-term debt). C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1198 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY years t and t + 1. We examine both years t and t + 1 because empirical and anecdotal evidence suggests that changes in debt-ratings occur with some time lag (Reiter 1990; Ziebart and Reiter, 1992; and Standard and Poor’s, 2001). 12 For example, firms are often placed on Standard & Poor’s CreditWatch before the rating is formally changed. The independent variables in equation (3) measure changes during year t in previously-defined variables so that both the dependent and independent variables reflect intertemporal changes. As a control for change in firm size, we include SIZEΔ, the change in the natural log of total assets. The test variable, RECLAMTΔ, is the change in the dollar amount of reclassified short-term obligations scaled by total assets. We also include a set of 12 indicator variables, IND j , to capture the firm’s industry. In their Corporate Rating Criteria, S&P explicitly states that they take industry information into account when forming a rating. Therefore, we assign firms to industry groups based on S&P’s Global Industry Classification Standard. Table 1, Panel B provides the S&P industry group definitions. To further test hypothesis 2, we include terms to examine the effects of decisions to begin and end the practice of reclassifying debt on the balance sheet (i.e., reclassification changes): RATINGΔi, t0+1 = β0 + β1 + β2 ROAΔi, t + β3 LEVΔi, t + β4 CRATIOΔi, t + β5 CFOΔi, t + β6 SIZEΔi, t + β7 RECLAMTΔi, t + β8 STARTi, t + β9 STOPi, t + β10 (STARTi, t × RECLAMTi, t ) + β11 (STOPi, t × RECLAMTi, t−1 ) + 23 j =12 β j INDi + υi, t . (4) In this equation, we code START t−1 as ‘1’ if the firm began reclassifying short-term debt during year t − 1, and STOP t−1 as ‘1’ if the firm stopped reclassifying all short-term debt during year t − 1 (i.e., the firm reclassified debt in year t − 2 but did not reclassify in year t − 1). The interaction terms multiply indicator variables START and STOP by the amount of reclassified short-term obligations scaled by total assets. Ceteris paribus, debt-rating upgrades (downgrades) are more likely for firms with increasing (decreasing) profitability, liquidity and cash flow, so that the control variables ROAΔ, CRATIOΔ and CFOΔ should have positive coefficients. In contrast, firms with increasing (decreasing) leverage are less (more) likely to experience positive (negative) debt rating changes; thus, we expect a negative coefficient for LEVΔ. We offer no prediction for SIZEΔ, a growth measure. Consistent growth could signal healthy cash flow and stable management, but rapid growth might also make the company too difficult to manage or imply more future borrowing. 13 We expect that a firm is more likely to receive a debt-rating downgrade when the amount reclassified increases during the year as well as when reclassification begins. Consequently, we predict negative 12 Robustness tests using only debt rating changes in year t reveal somewhat weaker results but do not change our conclusions about the effect of reclassification on debt ratings. 13 Nearly one-third of credit downgrades between 1984 and 1989 resulted from hostile acquisitions or from companies’ actions to defend themselves against takeover (Picker, 1991). C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES 1199 coefficients on both RECLAMTΔ and on the interaction term START × RECLAMT (i.e., β 7 < 0 and β 10 < 0). We also expect that debt-rating upgrades are more likely when firms declassify and predict a positive coefficient on STOP × RECLAMT (i.e. β 11 > 0). (v) Models of the Association Between Reclassification and Market Value of Equity We use the following model based on Ohlson (1995) to test whether reclassified liabilities are incrementally value-relevant to the amount of total liabilities (i.e, hypothesis 3): MVEi, t = β0 + β1 BVAi, t + β2 BVLi, t + β3 AEi, t + β4 RECLAMTi, t + υi, t . (5) We measure the market value of the firm’s common equity (MVE t ) three months after the end of fiscal year t to ensure that the firm’s stock price impounds the reclassification information reported in the footnotes to the financial statement for fiscal year t. 14 BVA is the book value of total assets; BVL is the book value of total liabilities including the reclassified amount. To calculate abnormal earnings AE, we first calculate an expected return as twelve percent of the book value of equity at the beginning of the year (i.e. 0.12 × [BVA t−1 − BVL t−1 ]). 15 AE is the difference between reported earnings and the calculated expected return. RECLAMT t is the dollar amount of short-term obligations reclassified as long term during year t. Consistent with many prior studies (see Barth et al., 2001 for a summary), we expect that BVA and BVL will indicate positive and negative coefficients, respectively. If reclassification is a signal of management’s intervention in the financial reporting process, greater amounts of reclassified obligations will be associated with lower firm value (i.e. the coefficient on RECLAMT will be negative). Alternatively, to test whether changes in reclassification have an even greater impact on market values than the level of reclassified short-term obligations, we refine equation (5) to estimate a model that separately examines coefficients for amounts initially classified and declassified amounts. 16 When reclassification occurred in the prior year but no reclassification occurs in the current year, the prior-year reclassification amount is considered declassified: MVEi, t = β0 + β1 BVAi, t + β2 BVLi, t + β3 AEi, t + β4 STARTi, t + β5 STOPi, t + β6 (RECLAMTi, t − RECLAMTi, t−1 ) + β7 (STARTi, t × RECLAMTi, t ) + β8 (STOPi, t × RECLAMTi, t−1 ) + υi, t . (6) 14 As a robustness test, we estimate our market-value models using market value of equity at the end of fiscal year t and our inferences do not change. 15 Abarbanell and Bernard (2000) report consistent results for abnormal earnings calculated with discount rates ranging from 9 to 15 percent. Their calculations hold rates constant across time and firms. As a robustness test, we also calculate abnormal earnings using alternative rates and our findings are qualitatively unchanged. 16 Econometrically, a model with an interaction term should also include both main-effect variables. Thus, our model should include both current and lagged reclassified amount. We include the change in reclassified amount (current minus lagged reclassified amount) in lieu of each variable separately. This facilitates the interpretation of the estimated coefficient. C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1200 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY We predict that initial reclassification will decrease equity values (i.e. β 4 < 0 and β 7 < 0). Further, declassification provides a signal that economic conditions will improve and therefore declassification is predicted to be associated with greater equity values (i.e. β 5 > 0 and β 8 > 0). 4. RESULTS (i) Sample and Descriptive Statistics Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for our sample. Panel A explains the sampleselection process and Panel B shows that 932 of the 1,684 sample firm-years indicate reclassifications of short-term debt as long-term. As Panel B shows, the sample appears to be heavily weighted in media industries (i.e., SIC 27 and 48) but both reclassification and non-reclassification firm-years are fairly well distributed among the other industry groups. Panel C reveals that reclassification activity increased substantially across the decade, beginning with only 49 reclassifications in 1989 and peaking with 113 in 1998. Table 2 compares reclassifying and non-reclassifying firm-years on several dimensions. When firms reclassify, they are larger, as measured both by the mean and median book value of assets (p < 0.01) and the market value of equity (mean p < 0.05; median p < 0.01). Reclassifying firms exhibit higher mean and median asset growth rates (p < 0.01). The amount reclassified is statistically significant, as indicated by the $564 million mean ($252 million median) amount reclassified (p < 0.01). Reclassification significantly changes long-term debt and current ratios: mean and median longterm debt ratios, as reported on the balance sheet, are greater for reclassifying firm years than for non-reclassifying firm years (p < 0.01). But backing out the reclassified amount reverses the direction of the difference: reclassifiers’ mean and median longterm debt ratios are statistically smaller than those of non-reclassifiers (p < 0.01). More dramatic, however, is the comparison of the current ratio before and after the effects of reclassification. In particular, the mean current ratio without reclassification is less than 1, reclassification boosts the mean above 1 (mean = 1.202). Comparing the nonreclassifying and reclassifying firm years, we see that reported mean and median current ratios are lower in reclassifying firm years than in non-reclassifying firm years (1.20 compared to 1.48). Without reclassification the differences are startling (0.95 compared to 1.48). (ii) Findings Regarding Firms’ Reclassification Decisions Table 3 reports results for our logistic regressions (equations (1) and (2)) that explain firms’ reclassification decisions. Both equations compare firm-years without reclassification to firm-years with reclassification for the same set of firms (i.e., ‘Sample 1’). Clearly, current ratio influences the reclassification decision—the lower the current ratio, the more likely the firm is to reclassify, as indicated by the negative coefficient on CRATIO (p < 0.01). The negative coefficient on LEV (p < 0.01) also indicates that firms reclassify when they can afford to—when leverage is low and can afford to have the C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation C Assets, $ millions Market value of equity, $ millions Return on assets Cash from operations to assets Asset growth Reclassified amount, $ millions Long-term debt to assets, as reported Long-term debt to assets, without reclassification Current ratio, as reported† Current ratio, without reclassification† Number (percent) of debt-rating downgrades Attributes 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1.546 1.190 0.221∗∗ 1.266∗ 1.266∗∗ 0.234∗∗ 1.480∗∗ 1.480∗∗ (17.0%) 1.018 0.740 0.269 0.221 4.1% 0 4.1% 9.4% 3,449 2,297 Median 0.963 0.963 0.135 0.135 −2.8% 0 1.9% 5.5% 1,607 1,087 25 th Percentile Firm-years Without Reclassification (N = 752) 0.234 8.6% 0 4.1% 9.3% 6,179 6,489 (19.0%) 1.202 0.950 1.330 1.012 0.111 0.344 15.1% 590 7.2% 13.5% 11,466 9,357 Mean 128 0.195 0.204 0.184 −1.2% 100 2.0% 6.5% 2,158 1,837 75 th Percentile 177 0.268∗∗ 5.6%∗∗ 252∗∗ 21.9%∗∗ 564∗∗ 0.275∗∗ 4.2% 9.8%∗ 5,022 3,761∗∗ ∗∗ Median 4.4% 10.1%∗ 9,332 8,217∗ ∗∗ Mean 25 th Percentile Firm-years With Reclassification (N = 932) Table 2 Comparison of 1,684 Firm-years With and Without Reclassification Between 1989 and 2000 1.744 1.744 0.311 0.311 12.0% 0 7.6% 13.3% 6,495 5,302 75 th Percentile DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES 1201 (12.0%) (10.6%) Mean 90 Median 99 Mean 75 th Percentile Median 25 th Percentile Firm-years Without Reclassification (N = 752) 75 th Percentile Notes: The table reports mean, median, 25th and 75th percentile levels for 12 attributes for 932 reclassifying firm-years and 752 non-reclassifying firm-years. Assets and the market value of equity are measured at the end of the year. Return on assets is income before extraordinary items divided by end-of-year total assets. Cash from operations is as reported on the cash flow statement, divided by end-of-year total assets. Asset growth is the percentage change in total assets from the beginning to end of year. The reclassified amount is the dollar amount of short-term debt reclassified as long-term pursuant to SFAS 6, as reported in the firm’s financial statement footnote. Long-term debt is divided by end-of-year total assets, and is shown two ways: first as reported on the financial statement and second after removing the amount of short-term debt reclassified to long-term. Current ratio is current assets divided by current liabilities and is shown two ways: first as reported on the financial statement and second after replacing the amount of short-term debt reclassified to long-term. † Compustat does not report values of both current assets and current liabilities for all firms in the sample. Of 932 (752) reclassification (non-reclassification) firm-years, 867 (707) report data sufficient to compute the current ratio. ∗ (∗∗) Indicates that either ‘firm-years with reclassification’ or ‘firm-years without reclassification’ measure is larger and significant at the 0.05 (0.01) level using a two-sample t-test of means, a Wilcoxon signed-rank tests of medians or, in comparing proportions of firm-years with debt rating changes, a non-parametric binomial test. Significance levels are reported assuming a two-tail distribution. Number (percent) of debt-rating upgrades Attributes 25 th Percentile Firm-years With Reclassification (N = 932) Table 2(Continued) 1202 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation (?) (−) (−) (−) (−) (+) Intercept ROA i,t LEV i,t CRATIO i,t CFO i,t RECLASS i,t−1 Model likelihood Chi-square Psuedo-R 2 (Predicted sign) Variable Equation (2) Estimate (χ 2 ) −1.044∗∗∗ (125.26) 0.986 (0.63) −2.612∗∗∗ (23.01) −1.534∗∗∗ (94.21) −0.230 (0.027) 3.006∗∗∗ (445.42) 840.84 41% Equation (1) Estimate (χ 2 ) 0.870∗∗∗ (11.23) 0.105 (0.01) −2.703∗∗∗ (27.15) −1.299∗∗∗ (90.53) 0.253 (0.03) 3.012∗∗∗ (449.07) 834.94 41% Sample 1 (N = 1,574)† 1.123∗∗ (5.49) −3.335 (1.98) −3.329∗∗∗ (8.03) −1.081∗∗∗ (14.82) −3.321∗∗ (6.21) 17.527 (0.01) 651.41 59% Equation (1) Estimate (χ 2 ) −1.445∗∗∗ (109.11) −3.226 (1.88) −2.980∗∗ (6.12) −1.190∗∗∗ (14.90) −3.417∗∗ (6.37) 17.463 (0.01) 651.36 59% Equation (2) Estimate (χ 2 ) Sample 2 (N = 724)‡ Equation (2) : RECLASSi,t = β0 + β1 (ROAi,t − MedianROAi,t ) + β2 (LEVi,t − MedianLEVi,t ) +β3 (CRATIOi,t − MedianCRATIOi,t ) + β4 (CFOi,t − MedianCFOi,t ) + β5 RECLASSi,t−1 + υi,t Equation (1) : RECLASSi,t = β0 + β1 ROAi,t + β2 LEVi,t + β3 CRATIOi,t + β4 CFOi,t + β5 RECLASSi,t−1 + υi,t Table 3 Factors Explaining the Decision to Reclassify Short-term Debt as Long-term DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES 1203 (Predicted sign) 88% Equation (1) Estimate (χ 2 ) 88% Equation (2) Estimate (χ 2 ) 95% Equation (1) Estimate (χ 2 ) 95% Equation (2) Estimate (χ 2 ) Sample 2 (N = 724)‡ Notes: The table reports parameter estimates, χ 2 statistics, and explanatory power of a logistical regression using data for each firm i and year t. Sample 1 includes 1,574 of the 1,684 observations described in Table 2 because 110 observations did not report sufficient data to compute current ratio. Sample 2 includes the subset of 362 Sample 1 reclassification observations that can be matched with 362 firm-years that did not indicate reclassification during the period from 1989 to 2000. RECLASS is a binary variable indicating ‘1’ if the firm reclassified short-term debt to long-term, and zero otherwise. ROA is income before extraordinary items divided by end-of-year assets. LEV is long-term liabilities measured without the effect of any debt reclassification, divided by end-of-year assets. CRATIO is current assets divided by current liabilities measured without the effect of any debt reclassification. CFO is cash flow from operations reported on the cash flow statement divided by end-of-year assets. Equation (2) adjusts each of these variables except RECLASS by subtracting the firm’s industry median (see industry classifications in Table 1, Panel B). ∗∗∗ Significant at the 1% level in a two-tailed test. ∗∗ Significant at the 5% level in a two-tailed test. ∗ Significant at the 10% level in a two-tailed test. % correctly predicted Variable Sample 1 (N = 1,574)† Table 3(Continued) 1204 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES 1205 leverage ratio increase from the reclassification. 17 Taken together, our results suggest factors that motivate firms to reclassify and provide a backdrop to our empirical tests concerning the economic consequences of firms’ reclassification decisions. It might be argued that using firms as their own control could bias the results. To address this concern, we identify a size- and industry-matched control sample of firms’ (matched by year) that do not reclassify at any point during the 1989 to 2000 sample period. We label this matched-pairs sample, Sample 2. Table 3 shows that results are somewhat stronger for Sample 2. In particular, coefficients are more significant and CFO becomes significant in the predicted direction; the negative coefficient on CFO indicates that firms with declining cash flows are more likely to reclassify debt. Thus, our results are robust to estimation on a wider sample. (iii) Results of Tests for an Association Between Reclassification and Debt Ratings We use logistic regressions to estimate the effect of changes in the financial and reclassification variables on the likelihood of a firm experiencing a debt upgrade (or the likelihood of NOT experiencing a downgrade or no change in rating). Thus, in Table 4, positive (negative) coefficients imply that an upgrade is more (less) likely. 18 Consistent with prior studies (Ziebart and Reiter, 1992; and Hand et al., 1992), we find that upgrades are less frequent than downgrades—the intercept for downgrades is significantly greater than the intercept for upgrades in both equations (3) and (4). This may be driven, in part, by the upper bound on debt ratings. The estimated coefficients on the included financial variables are consistent with prior findings (Ziebart and Reiter, 1992), although not all of the coefficients are statistically significant. We find evidence that reclassification increases the likelihood of a debt-rating downgrade—the coefficient on RECLAMTΔ is negative in equation 3 (p < 0.01). Distinguishing between the directions of changes in reclassification behavior (i.e., initial reclassification, ongoing reclassification and declassification) in equation (4), significantly improves the power of the model. Specifically, the chi-square model likelihood increases from 82.45 (equation (3)) to 112.85 (equation (4)). The coefficient on initial reclassified amounts (START × RECLAMT) is negative and highly significant (β 10 = −12.098, p < 0.01), implying that credit analysts view reclassification as a ‘red flag,’ perhaps because they have private information about debt covenant violations or other economic factors related to the firms’ credit risk, or information about management’s intent to manage the firms’ financial reports. Contrary to expectations, we find a statistically insignificant coefficient on the interaction that captures declassification (STOP × RECLAMT). Thus, firms previously punished for reclassifying (with lowered bond ratings) do not appear to be rewarded when they declassify. 17 We also consider lagged debt ratings in these regressions as well as changes in debt ratings including the important drop from investment grade. These debt-rating coefficients (untabulated) were weak and mixed. Thus we conclude that firms do not appear to consider past debt-rating levels or changes in making reclassification choices. 18 We also estimate the models in Table 4 using ordered logistic regressions as suggested by Ederington (1985). Results (not reported here) confirm that initial reclassification exhibits the strongest association with debt-rating changes and that reclassification explains downgrades more than upgrades. We find weaker evidence that reclassification makes a difference in explaining upgrades compared to no changes in debt ratings. Our findings corroborate prior research that reports stronger evidence for downgrades than for upgrades (Hand et al., 1992; and Barron et al., 1997). C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation (?) (?) (+) (−) (+) (+) (?) Intercept for downgrade ROAΔ i,t LEVΔ i,t CRATIOΔ i,t CFOΔ i,t SIZEΔ i,t (Predicted sign) Intercept for upgrade Variable j =12 Equation (4) Estimate (χ 2 ) −2.144∗∗∗ (75.72) 1.200∗∗∗ (25.04) 4.656∗∗∗ (19.77) −6.648∗∗∗ (48.18) 0.009 (0.02) 1.083 (0.82) −0.144 (0.18) Equation (3) Estimate (χ 2 ) −2.14∗∗∗ (77.78) 1.171∗∗∗ (24.71) 4.693∗∗∗ (20.30) −6.220∗∗∗ (44.62) −0.031 (0.31) 1.000 (0.71) −0.207 (0.39) Equation (4) : RATINGΔi,t0+1 = β0 + β1 + β2 ROAΔi,t + β3 LEVΔi,t + β4 CRATIOΔi,t + β5 CFOΔi,t + β6 SIZEΔi,t + β7 RECLAMTΔi,t + β8 STARTi,t + β9 STOPi,t + β10 (STARTi,t × RECLAMTΔi,t ) 23 β j INDi + υi,t + β11 (STOPi,t × RECLAMTΔi,t ) + j =8 Equation (3) : RATINGΔi,t0+1 = β0 + β1 + β2 ROAΔi,t + β3 LEVΔi,t + β4 CRATIOΔi,t + β5 CFOΔi,t + β6 SIZEΔi,t 19 +β7 RECLAMTΔi,t + β j INDi + υi,t Table 4 Association Between Reclassified Amounts and Debt Rating Changes 1206 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation C (−) (+) (−) (+) START i,t STOP i,t START i,t × RECLAMTΔ i,t STOP i,t × RECLAMTΔ i,t 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 84.45 7.5% 65.0.% ∗∗ −4.348 (17.23) −12.098 (11.00) −3.412 (2.08) 112.85 8.9% 65.5% ∗∗∗ 0.762 (7.11) −0.023 (0.89) ∗∗∗ ∗∗ −4.805 (14.93) Notes: The table reports parameter estimates, χ 2 statistics, and explanatory power of a logistical regression using data for each firm i and year t. The sample consists of 1,298 observations: 722 reclassifying firm-years and 576 non-reclassifying firm-years. The sample includes 177 upgrades (RATINGΔ i,t0+1 = +1), 285 downgrades (RATINGΔ i,t0+1 = −1) and 836 observations with no rating change (RATINGΔ i,t0+1 = 0). RATINGΔ t+1,2 is +1 for a Standard & Poors senior debt rating upgrade in year t + 1 or year t + 2, −1 for a debt rating downgrade, and 0 for a debt rating that remains unchanged. ROAΔ t is the change from year t − 1 to year t in the ratio of earnings before extraordinary items divided by total assets. LEVΔ t is the change from year t − 1 to year t in the ratio of long-term liabilities measured without the effect of any debt reclassification, divided by total assets. CRATIOΔ t is the change from year t − 1 to year t in the ratio of current assets to current liabilities measured without the effect of any debt reclassification. CFOΔ t is the change from year t − 1 to year t in the ratio of cash flow from operations reported on the cash flow statement, divided by end-of-year assets. SIZEΔ t is the change from year t − 1 to year t in the natural log of total assets. RECLAMTΔ is the change from year t − 1 to year t in the amount of short-term debt reclassified as long-term, scaled by total assets. START is a binary variable indicating ‘1’ if short-term obligations are reclassified in the current year but not in the prior year, and zero otherwise. STOP is a binary variable indicating ‘1’ if short-term obligations are reclassified in the prior year but not in the current year, and zero otherwise. IND j is a binary variable indicating ‘1’ if the firm operates in industry j, and zero otherwise. Table 1 Panel B provides industry definitions, the wood products industry is the omitted base group, and coefficients on the industry variables are suppressed. ∗∗∗ Significant at the 1% level in a two-tailed test. ∗∗ Significant at the 5% level in a two-tailed test. ∗ Significant at the 10% level in a two-tailed test. Model likelihood Chi-square Psuedo-R 2 % correctly predicted (−) RECLAMTΔ i,t DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES 1207 1208 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY (iv) Results of Tests for an Association Between Reclassification and Market Value of Equity Table 5 reports results for our ordinary least squares regression of market values of equity on book values of assets and liabilities, and abnormal earnings (i.e., equation (5)). Contrary to our expectation, the coefficient on RECLAMT is not statistically significant. Thus, whether a firm reclassifies short-term obligations does not appear to be an equity value-relevant signal. However, we find significant results when we distinguish among reclassification behaviors: equation (6) includes indicator variables and interaction terms to examine the separate effects of initial reclassification and declassification. Neither of the coefficients for the indicator variables START or STOP is significantly different from zero. However, we find that the market value of equity decreases when the amount of reclassified debt increases (β 6 = −1.243, p = 0.0259). On average, for every additional dollar of debt reclassified, equity market value decreases by $1.24, controlling for the levels of assets, liabilities and abnormal earnings. Table 5 also shows that when firms cease reclassification, market value increases significantly in relation to the amount declassified; the coefficient on STOP × RECLAMT is 2.659 (p < 0.01). This implies that for every dollar of short-term obligations returned to the short-term liability section of the balance sheet, the average firm’s market value increases by $2.66. Investors apparently perceive declassification as a very positive signal. Comparing the results of equations (5) and (6), we learn that it is not merely the act of reclassification that impacts firm value. Investors apparently pay attention to the magnitude of the change in the reclassified amount. We reiterate that we cannot explicitly identify the mechanism by which reclassification and declassification affect market value. However, by identifying reclassification and declassification as valuerelevant signals, we have identified a leading indicator that is publicly available to investors and other market participants. (v) Robustness Tests We performed a number of tests to assess the robustness of our findings. None of the tests described here changed our inferences. We omitted outliers identified using methods advocated by Belsley, Kuh, and Welsch (1980) in all the regression models reported in Tables 3 through 5. We winsorized observations in the lowest and highest percentile for the continuous variables in the logistic and ordinary least-squares regression models to remove the potentially powerful effects of extreme observations. In our debt-rating models (Table 4), we deflated the continuous financial variables by book value as well as by market value of firms’ equity instead of by total assets. We considered a number of other financial variables in our debt-rating models, including variables that measured interest expense and interest coverage, working capital levels rather than current ratio, and indicator variables for each year in the time-series; none of these variables improved the models’ explanatory power or changed our inferences. 5. CONCLUSION This study finds that firms’ reclassification of short-term debt to long term is not innocuous balance sheet presentation. The reclassification decision appears to be a deliberate financial reporting strategy with economic implications and consequences. C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1209 DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES Table 5 Association Between Reclassified Amounts and Market Value of Equity Equation (5) : MVEi,t = β0 + β1 BVAi,t + β2 BVLi,t + β3 AEi,t + β4 RECLAMTi,t + υi,t Equation (6) : MVEi,t = β0 + β1 BVAi,t + β2 BVLi,t + β3 AEi,t + β4 STARTi,t + β5 STOPi,t +β6 (RECLAMTi,t − RECLAMTi,t−1 ) +β7 (STARTi,t × RECLAMTi,t ) +β8 (STOPi,t × RECLAMTi,t−1 ) + υi,t Variable (Predicted sign) Intercept (?) BVA i,t (+) BVL i,t (−) AE i,t (+) RECLAMT i,t (−) START i,t (−) STOP i,t (+) RECLAMT i,t − RECLAMT i,t−1 (−) START i,t × RECLAMT i,t (−) STOP i,t × RECLAMT i,t−1 (+) Adjusted R 2 Equation (5) Estimate (t-statistic) ∗∗∗ 911.453 (3.10) ∗∗∗ 2.945 (27.45) ∗∗∗ −3.099 (−23.12) ∗∗∗ 12.870 (24.05) 0.139 (0.41) 55.9% Equation (6) Estimate (t-statistic) ∗∗∗ 1, 102.450 (3.47) ∗∗∗ 2.964 (28.10) ∗∗∗ −3.132 (−23.46) ∗∗∗ 13.170 (24.39) −905.634 (−1.08) −1, 434.492 (−1.48) ∗∗ −1.243 (−2.23) 1.052 (1.00) ∗∗∗ 2.659 (2.18) 56.3% Notes: The table reports parameter estimates and t-statistics for an OLS regression using data for each firm i and year t. The sample consists of 1,684 observations: 932 reclassifying firm-years and 752 non-reclassifying firm years. MVE is the market value of common equity measured three months after the end of year t. BVA is end-of-year total assets in $ millions. BVL is end-of-year total liabilities in $ millions. AE is abnormal earnings measured by earnings before extraordinary items less 12 percent of prior-year net book value (i.e., BVA minus BVL). RECLAMT t is the amount of short-term debt reclassified as long-term in year t. START is a binary variable indicating ‘1’ if short-term obligations are reclassified in the current year but not in the prior year, and zero otherwise. STOP is a binary variable indicating ‘1’ if short-term obligations are reclassified in the prior year but not in the current year, and zero otherwise. ∗∗∗ Significant at the 1% level in a two-tailed test. ∗∗ Significant at the 5% level in a two-tailed test. ∗ Significant at the 10% level in a two-tailed test. Consistent with prior research, we show that firms reclassify when they need to (i.e., when current ratio is lower than in the previous year or lower than the industry benchmark) and when they can afford to (i.e., when overall leverage is lower than in the previous year or lower than the industry benchmark). C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1210 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY We find that firms’ debt ratings are negatively affected by reclassification. In particular, initial reclassification increases the likelihood of a rating downgrade. This evidence implies that although managers may strategically classify short-term debt as long-term, credit analysts do not reward this behavior with increased ratings or, consequently, lower cost of capital. We also find that the market value of firms’ equity is associated with the decision to declassify short-term obligations, but not with the decision to initially reclassify debt. Although declassification saves the firm real costs (i.e., the elimination of long-term loan commitment fees), the magnitude of this cost saving cannot explain the magnitude of the price changes we document. Firm reclassification decisions are not likely to have caused changes in debt ratings or market values. Rather, the economic consequences that we document are likely caused by other factors that are correlated with firms’ reclassification decisions. So while our models may suffer from correlated omitted variables problems, we contend that the publicly available reclassification and declassification actions proxy for these unspecified unobservable variables. Overall, our results imply that debt reclassification signals bad news—it is a red flag to capital market participants. Conversely, declassification signals good news. As such, our findings are important to creditors, investors, and other market participants who seek information concerning debt and equity prices. Moreover, this study contributes to the general understanding of the determinants and consequences of accounting choice as it pertains to the balance sheet. Much of the extant research on accounting choice focuses on earnings management (see Holthausen and Leftwich, 1983; and Fields et al., 2001), while comparably little has been written about balance sheet management. This perhaps is because managerial motivation is less obvious for balance sheet accounts than for earnings (although see Imhoff and Thomas, 1988; Mohr, 1988; and Hopkins, 1996). Our findings suggest several avenues for further research. For example, one might explore whether firms that engage in balance sheet management via debt reclassification also engage in income statement management. In particular, future research could explore whether the quality of firms’ earnings, perhaps measured by the persistence of earnings, cash flows and/or accruals, is related to decisions to initiate or cease reclassification. Alternately, one might assess whether firms that reclassify do so in conjunction with deliberate economic choices that impact earnings. These sorts of studies would provide evidence on the simultaneous management of the balance sheet and income statement and would speak to management’s broader reporting philosophy. Future research might profitably extend our study by using international data particularly when firms adopt IAS standards in 2005. IAS 1, which addresses the phenomenon we document in this paper, is more stringent in some respects than SFAS 6. 19 Consequently, the market is likely to learn of potential liquidity problems sooner. In the extreme, this IFRS mandate for classifying short term may be too conservative, causing covenant breaches and potentially causing firms that have no liquidity problems appear as if they do (Ormrod and Taylor, 2004). Whether the 19 Specifically, under IAS 1, Presentation of Financial Statements, firms that have long term debt covenant breaches or debt maturing within the next fiscal year must classify the debt as current even if the firm 1) obtains a waiver on the covenant breach after the balance sheet date or 2) actually refinances the debt after the balance sheet date but before the release date of the financial statements. C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation DEBT CLASSIFICATION AND MARKET CONSEQUENCES 1211 equity and debt markets will view classification toward short term debt under IFRS as a ‘problem’ or not is an empirical question that future research could investigate. Conversely, compared with many domestic accounting standards, IAS standards provide more leeway in measuring and classifying balance sheet items that affect debt covenants. Specifically, the increased discretion provided by IAS standards regarding accruals and the definition of current versus non-current assets and liabilities, may enable firms to avoid debt covenant violations (Ormrod and Taylor, 2004). Thus, future research could investigate the extent to which firms exercise discretion over the measurement and classification of current or non-current items in the new IAS regime, and the debt and equity market consequences of such decisions. REFERENCES Abarbanell, J. and V. Bernard (2000), ‘Is the US Stock Market Myopic?’, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 38, No. 2 (Autumn), pp. 221–47. Altman, E. (2000), ‘Predicting Financial Distress of Companies: Revisiting the Z-score and ZETA Models’, Working Paper (New York University). Barron, M., A. Clare and S. Thomas (1997), ‘The Effect of Bond Rating Changes and New Ratings on UK Stock Returns’, Journal of Business Finance & Accounting , Vol. 24, Nos. 3&4 (April), pp. 497–509. Barth, M., W. Beaver and W. Landsman (2001), ‘The Relevance of the Value Relevance Literature for Financial Accounting Standard Setting: Another View’, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 31, Nos. 1–3 (September), pp. 77–104. ——— ———, J. Hand and W. Landsman (1999), ‘Accruals, Cash Flows, and Equity Values’, Review of Accounting Studies, Vol. 4, Nos. 3&4 (December), pp. 205–29. Beatty, A., K. Ramesh and J. Weber (2002), ‘The Importance of Accounting Changes in Debt Contracts: The Cost of Flexibility in Covenant Calculations’, Journal of Accounting & Economics, Vol. 33, No. 2 (June), pp. 205–27. Belsley, D., E. Kuh and R. Welsch (1980), Regression Diagnostics (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc). Butler, A. and K. Rodgers (2003), ‘Relationship Rating: How Do Bond-rating Agencies Process Information’, Working Paper (Rice University and Pennsylvania State University). Cantwell, J. (1998), ‘Managing Credit Ratings and Rating Agency Relationships’, TMA Journal, Vol. 18, pp. 14–22. Credit (1991), ‘Rating Agencies Answer Questions’, Credit, Anonymous author, Vol. 17, pp. 13–16. Dichev, I. and J. Piotroski (2001), ‘The Long-run Stock Returns Following Bond Ratings Changes’, Journal of Finance, Vol. 56, No. 1 (February), pp. 173–203. Ederington, L. (1985), ‘Classification Models and Bond Ratings,’ The Financial Review, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 237–61. Fields, T., T. Lys and L. Vincent (2001), ‘Empirical Research on Accounting Choice’, Journal of Accounting & Economics, Vol. 31, Nos. 1–3 (September), pp. 255–307. Financial Accounting Standards Board (1975), Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 6: Classification of Short-term Obligations Expected to be Refinanced (Stamford, CT: FASB). ——— (1980), Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 2 (Stamford, CT: FASB). Gramlich, J., M.L. McAnally and J. Thomas (2001), ‘Balance Sheet Management: The Case of Short-term Obligations that are Reclassified as Long-term Debt’, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 39, No. 2 (September), pp. 283–96. Hand, J., R. Holthausen and R. Leftwich (1992), ‘The Effects of Bond Rating Agency Announcements on Bond and Stock Prices’, Journal of Finance, Vol. 47, No. 2 (June), pp. 733–52. Holthausen, R. and R. Leftwich (1983), ‘The Economic Consequences of Accounting Choice: Implications of Costly Contracting and Monitoring’, Journal of Accounting & Economics, Vol. 5, pp. 77–117. C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation 1212 GRAMLICH, MAYEW AND McANALLY Hopkins, P. (1996), ‘The Effect of Financial Statement Classification of Hybrid Financial Instruments on Financial Analysts’ Stock Price Judgments’, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Supplement), pp. 33–50. IASB (2003), ‘IAS 1, Presentation of Financial Statements’ (London, UK: International Accounting Standards Board). Imhoff, E. and J. Thomas (1988), ‘Economic Consequences of Accounting Standards: The Lease Disclosure Rule Change’, Journal of Accounting & Economics, Vol. 10, No. 4 (December), pp. 277–310. Kliger, D. and O. Sarig (2000), ‘The Information Value of Bond Ratings’, Journal of Finance, Vol. 55, No. 6 (December), pp. 2879–902. Kormendi, R. and R. Lipe (1987), ‘Earnings Innovations, Earnings Persistence, and Stock Returns’, Journal of Business, Vol. 60, No. 3, pp. 323–45. Lev, B. (1969), ‘Industry Averages as Targets for Financial Ratios’, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Autumn), pp. 290–99. Maddala, G. (1983), Limited-dependent and Qualitative Variables in Econometrics (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press). Mester, L. (1997), ‘What’s the Point in Credit Scoring?’, Federal Bank of Philadelphia Business Review (September/October), pp. 3–16. Millon, M. and A. Thakor (1985), ‘Moral Hazard and Information Sharing: A Model of Financial Information Gathering Agencies’, Journal of Finance, Vol. 40, No. 5 (December), pp. 1403–22. Mohr, R. (1988), ‘Unconsolidated Finance Subsidiaries: Characteristics and Debt/Equity Effects’, Accounting Horizons, Vol. 2, No. 1 (March), pp. 27–34. Ohlson, J. (1995), ‘Earnings, Book Values and Dividends in Security Valuation’, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Spring), pp. 661–87. Ormrod, P. and P. Taylor (2004), ‘The Impact of the Change to International Accounting Standards on Debt Covenants: A U.K. Perspective’, Accounting in Europe, Vol. 1, pp. 71–94. Picker, I. (1991), ‘The Ratings Game’, Institutional Investor , Vol. 25 (September), pp. 73–77. Reiter, S. (1990), ‘The Use of Bond Market Data in Accounting Research’, Journal of Accounting Literature, Vol. 9, pp. 183–228. Standard and Poor’s (2001), Corporate Rating Criteria (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies). Ziebart, D. and S. Reiter (1992), ‘Bond Ratings, Bond Yields, and Financial Information’, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Fall), pp. 252–82. C 2006 The Authors C Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006 Journal compilation