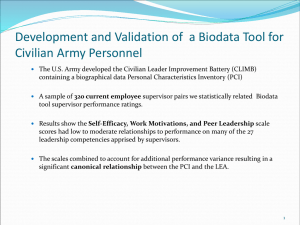

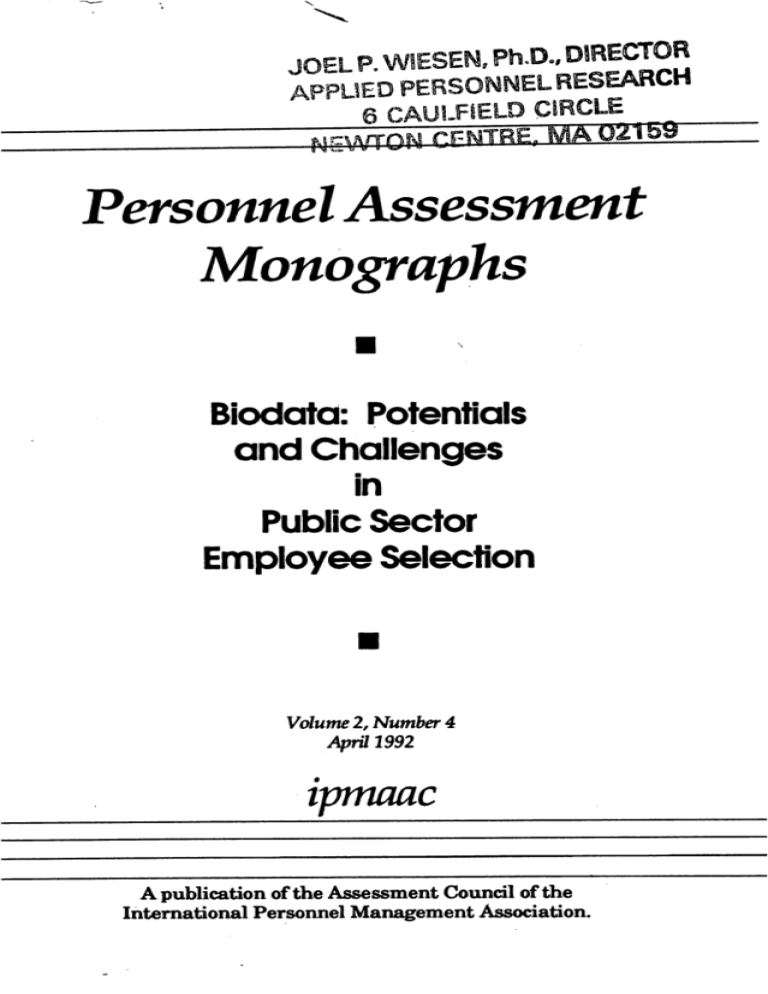

Potentials and Challenges in Public Sector Employee Selection

advertisement