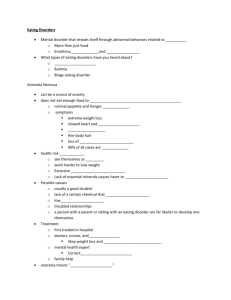

Excessive Exercise-Quality & Quantity and more

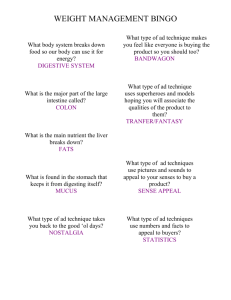

advertisement