The Rise and Fall of the World's Largest Wine Exporter—And Its

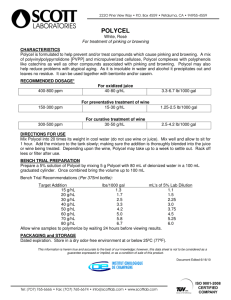

advertisement