River Eels - NSW Department of Primary Industries

advertisement

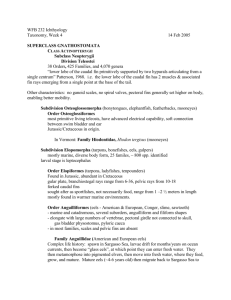

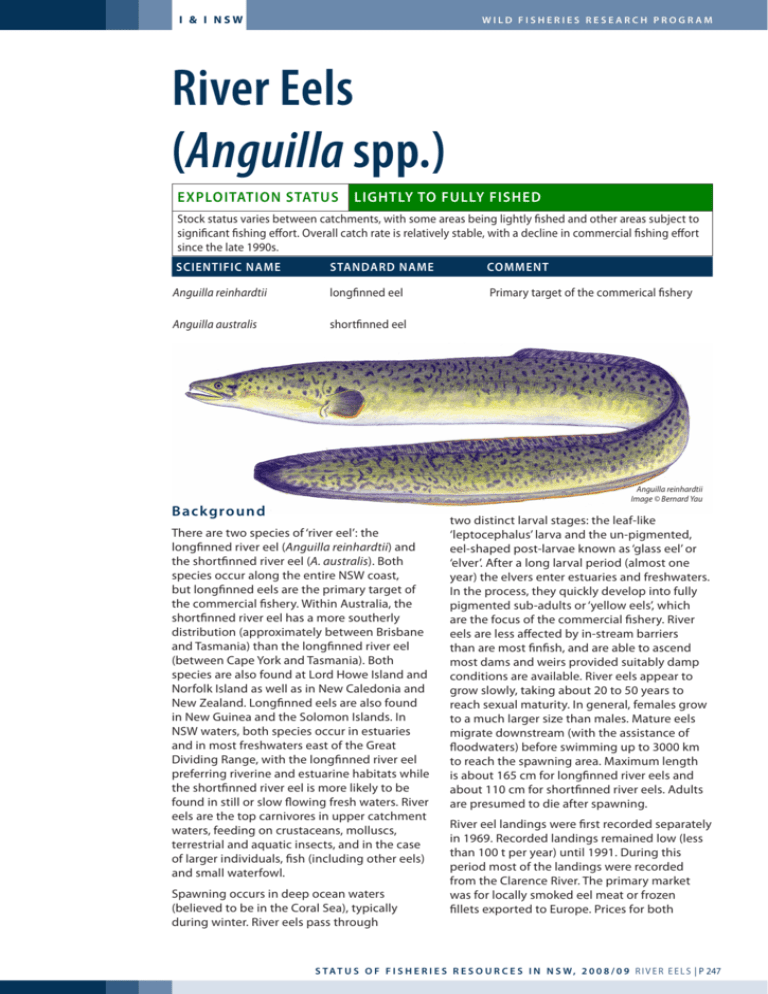

I & I NSW Wild Fisheries research Program River Eels (Anguilla spp.) Exploitation Status lightly to Fully Fished Stock status varies between catchments, with some areas being lightly fished and other areas subject to significant fishing effort. Overall catch rate is relatively stable, with a decline in commercial fishing effort since the late 1990s. Scientific name Standard name comment Anguilla reinhardtii longfinned eel Primary target of the commerical fishery Anguilla australis shortfinned eel Anguilla reinhardtii Image © Bernard Yau Background There are two species of ‘river eel’: the longfinned river eel (Anguilla reinhardtii) and the shortfinned river eel (A. australis). Both species occur along the entire NSW coast, but longfinned eels are the primary target of the commercial fishery. Within Australia, the shortfinned river eel has a more southerly distribution (approximately between Brisbane and Tasmania) than the longfinned river eel (between Cape York and Tasmania). Both species are also found at Lord Howe Island and Norfolk Island as well as in New Caledonia and New Zealand. Longfinned eels are also found in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. In NSW waters, both species occur in estuaries and in most freshwaters east of the Great Dividing Range, with the longfinned river eel preferring riverine and estuarine habitats while the shortfinned river eel is more likely to be found in still or slow flowing fresh waters. River eels are the top carnivores in upper catchment waters, feeding on crustaceans, molluscs, terrestrial and aquatic insects, and in the case of larger individuals, fish (including other eels) and small waterfowl. Spawning occurs in deep ocean waters (believed to be in the Coral Sea), typically during winter. River eels pass through two distinct larval stages: the leaf-like ‘leptocephalus’ larva and the un-pigmented, eel-shaped post-larvae known as ‘glass eel’ or ‘elver’. After a long larval period (almost one year) the elvers enter estuaries and freshwaters. In the process, they quickly develop into fully pigmented sub-adults or ‘yellow eels’, which are the focus of the commercial fishery. River eels are less affected by in-stream barriers than are most finfish, and are able to ascend most dams and weirs provided suitably damp conditions are available. River eels appear to grow slowly, taking about 20 to 50 years to reach sexual maturity. In general, females grow to a much larger size than males. Mature eels migrate downstream (with the assistance of floodwaters) before swimming up to 3000 km to reach the spawning area. Maximum length is about 165 cm for longfinned river eels and about 110 cm for shortfinned river eels. Adults are presumed to die after spawning. River eel landings were first recorded separately in 1969. Recorded landings remained low (less than 100 t per year) until 1991. During this period most of the landings were recorded from the Clarence River. The primary market was for locally smoked eel meat or frozen fillets exported to Europe. Prices for both s t a t u s o f f i s h e r i e s r e s o u r c e s i n n s w , 2 0 0 8 / 0 9 R i v er E e l s | p 247 wild fisheries research program Recreational Catch of River Eels The annual recreational harvest of river eels in NSW is likely to be less than 10 t. This estimate is based upon the results of the offsite National Recreational and Indigenous Fishing Survey (Henry and Lyle, 2003) and onsite surveys undertaken by I & I NSW. Historical Landings of River Eels • Recreational landings are not accurately known, and may be significant in some catchments near population centres. • There is a minimum legal length of 58 cm and recreational bag limit of 10 longfinned eels and a minimum legal length of 30 cm and recreational bag limit of 10 shortfinned eels. 150 100 Landings (t) 50 Financial Year Commercial landings (including available historical records) of river eels for NSW from 1990/91 to 2008/09 for all fishing methods. Catches from impoundments are not included in this figure. Landings by Commercial Fishery of River Eels 200 Estuary General (Primary Species) 50 • Commercial landings fluctuate over time, and have declined over the past decade - but analysis is confounded by a reduction in fishing effort and the possible effects of the drought. After declining in the 1990s, recent commercial catch rates are relatively stable. 90/91 92/93 94/95 96/97 98/99 00/01 02/03 04/05 06/07 08/09 0 • With the exception of some impoundments where fishing occurs under permit, commercial fishing is not allowed in freshwater (where the majority of female eels occur). 0 • River eels represent an economically valuable fishery, with precautionary management strategies in place because of the complex life history of these long lived species. Landings (t) Additional Notes 200 Eels are taken almost exclusively in eel traps. Most of the catch is exported live to China and a very small proportion of the catch is sold as whole fish through the Sydney Fish Market. 150 Peaks in eel fishing activity vary between catchments. In the Clarence River eel trapping is generally a winter activity. Commercial eel fishing in the Hawkesbury River, however, peaks earlier in the year, and is possibly market driven to supply the high export demand for the Chinese New Year. Catch 100 markets were relatively low. In the early 1990s, a high value market developed for live eels for export to China. Fishing effort in the estuaries increased substantially and permits were issued for harvesting from impoundments in 1991. 97/98 99/00 01/02 03/04 05/06 07/08 Financial Year Reported landings of river eels by NSW commercial fisheries from 1997/98. Fisheries which contribute less than 2.5% of the landings are excluded for clarity and privacy. Catches from impoundments are excluded from this figure. p 248 | R i v er E e l s s tat u s o f f i s h e r i e s r e s o u r c e s i n n s w, 2 0 0 8 / 0 9 Catch Per Unit Effort Information of River Eels Harvested by Eel Trapping in NSW 1.0 Pease, B.C., V. Silberschneider and T. Walford (2002). Upstream migration by glass eels of two Anguilla species in the Hacking River, New South Wales, Australia, American Fisheries Society Symposium 33. 0.6 0.4 Queensland Fisheries. (2010). Stock status of Queensland’s fisheries resources 2009-10. Queensland, Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation: 65 pp. 0.0 0.2 Relative Catch Rate 0.8 Potter, I.C. and G.A. Hyndes (1999). Characteristics of the ichthyofaunas of southwestern Australian estuaries, including comparisons with holarctic estuaries and estuaries elsewhere in temperate Australia: A review. Australian Journal of Ecology 24: 395-421. 98/99 00/01 02/03 04/05 06/07 08/09 Financial Year Catch rates of river eels harvested using eel trapping for NSW. Two indicators are provided: (1) median catch rate (lower solid line); and (2) 90th percentile of the catch rate (upper dashed line). Note that catch rates are not a robust indicator of abundance in many cases. Caution should be applied when interpreting these results. Fur ther Reading Beumer, J.P. (1979). Feeding and movement of Anguilla australis and A. reinhardtii in Macleods Morass, Victoria, Australia. Journal of Fish Biology 14 (6): 573592. Henry, G.W. and J.M. Lyle (2003). The National Recreational and Indigenous Fishing Survey. Final Report to the Fisheries Research & Development Corporation and the Fisheries Action Program Project FRDC 1999/158. NSW Fisheries Final Report Series No. 48. 188. Cronulla, NSW Fisheries. McKinnon, L., R. Gasior, A. Collins, B. Pease and F. Ruwald (2002). Assessment of eastern Australian Anguilla australis and A. reinhardtii glass eel stocks. In: Assessment of Eastern Australian Glass Eel Stocks and Associated Eel Aquaculture. Final Report to Fisheries Research and Development Corporation Project 97/312 and 99/330. Alexandra, Vic, Marine and Freshwater Resources Institute. Pease, B.C. (2004). Description of the biology and an assessment of the fishery for adult longfinned eels in NSW. Final Report to Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. Project 1998/127. 167 pp. Sydney, NSW Fisheries. Pease, B.C., D.P. Reynolds and C.T. Walsh (2003). Validation of otolith age determination in Australian longfinned river eels, Anguilla reinhardtii. Marine and Freshwater Research 54: 995-1004. Silberschneider, V., B.C. Pease and D.J. Booth (2001). A novel artificial habitat collection device for studying resettlement patterns in anguillid glass eels, Journal of Fish Biology 58: 1359-1370. Silberschnieder, V., B.C. Pease and D.J. Booth (2004). Estuarine habitat preferences of Anguilla australis and A. reinhardtii glass eels as inferred from laboratory experiments, Environmental Biology of Fishes 71 (4): 395-402. Sloane, R.D. (1984). Distribution, abundance, growth and food of freshwater eels (Anguilla spp.) in the Douglas River, Tasmania. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 35: 325-339. Walsh, C.T. and B.C. Pease (2002). The use of clove oil as an anaesthetic for the longfinned eel, Anguilla reinhardtii (Steindachner), Aquaculture Research 33: 627-635. Walsh, C.T., B.C. Pease and D.J. Booth (2003). Sexual dimorphism and gonadal development of the Australian longfinned river eel, Journal of Fish Biology 63: 137-152. Walsh, C.T., B.C. Pease and D.J. Booth (2004). Variation in the sex ratio, size and age of longfinned eels within and among coastal catchments of southeastern Australia, Journal of Fish Biology 64: 12971312. Walsh, C.T., B.C. Pease, S.D. Hoyle and D.J. Booth (2006). Variability in growth of longfinned eels among coastal catchments of south-eastern Australia, Journal Fish Biology 68 1693-1706. Please visit the CSIRO website, http://www.marine.csiro.au/caab/ and search for the species code (CAAB) 37 056001 and 37 056002, common name or scientific name to find further information. © State of New South Wales through Industry and Investment NSW 2010. You may copy, distribute and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose, provided that you attribute Industry and Investment NSW as the owner. Disclaimer: The information contained in this publication is based on knowledge and understanding at the time of writing (April 2010). However, because of advances in knowledge, users are reminded of the need to ensure that information upon which they rely is up to date and to check currency of the information with the appropriate officer of Industry and Investment NSW or the user’s independent adviser. R i v er E e l s | p 249 wild fisheries research program p 250 | R i v er E e l s