2-Sarah Winslow.pmd - Serials Publications

advertisement

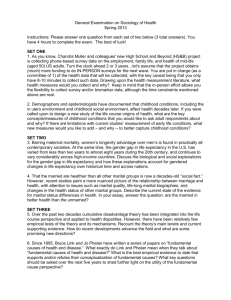

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY VOLUME 37, NUMBER 2, AUTUMN 2011 MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES’ INCOME ADVANTAGE* SARAH WINSLOW Clemson University In recent years, a growing body of research has examined the impact of wives’ absolute and relative income on marital quality and stability, yielding somewhat inconsistent results. However, like much research on the prevalence of wives who earn more than their husbands, these analyses have not fully accounted for the dynamic nature of wives’ earnings, particularly their earnings relative to those of their husbands. The analyses presented in this paper unite research on the impact of husbands’ and wives’ relative earnings with the growing body of literature on the prevalence and persistence of wives’ income advantage by utilizing panel data to examine the relationship between the duration of wives’ income advantage and marital conflict. The results indicate an inverted U-shaped relationship between marital conflict and the duration of wives income advantage—the highest levels of conflict are found among those couples in which the income advantage fluctuates between spouses over a period of years. The consequences of women’s employment for family life have been the focus of much sociological research and public scrutiny. One major topic of interest has been the relationship between wives’ labor market behavior, particularly their income, and marital quality or stability. The results of these analyses are mixed, with some finding that wives’ income and employment stabilize marriage (Schoen et al., 2006), others asserting that wives’ labor force participation and income increase conflict and instability (Perry-Jenkins and Folk, 1994; Rogers, 2004; Teachman, 2010), and still others indicating a curvilinear relationship between wives’ income and marital quality and stability (Ono, 1998; Rogers, 2004). A growing number of analyses have focused specifically on wives’ relative income * The author wishes to thank Bill Bielby, Mary Blair-Loy, Ellen Granberg, and Jerry A. Jacobs for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. This research was supported in part by a Woodrow Wilson Dissertation Fellowship in Women’s Studies and a Clemson University Department of Business and Behavioral Science Summer Research Grant. 204 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY advantage, yet the body of research on the impact of wives’ proportional contributions to total income on key outcomes in marriage—namely marital quality and stability—fails to fully account for the dynamic nature of husbands’ and wives’ relative earnings, despite recent research indicating that wives’ income advantages are overwhelmingly temporary rather than persistent (Winkler et al., 2005; Winslow-Bowe, 2006). This paper expands on previous research on the impact of husbands’ and wives’ relative income by utilizing panel data to examine the relationship between the duration of wives’ income advantage and marital conflict. Earnings are an important source of power. Feminist theories have argued that women’s economic dependency is a key mechanism through which women’s subordinate position in families and the labor market is created and maintained (Hartmann, 1976; Sorensen and McLanahan, 1993). Wives’ earnings relative to their husbands—and wives’ income advantage, in particular—provide “insight into the dynamics of marital power, equity, and challenges to husbands’ prerogatives as the primary breadwinner” (Rogers and DeBoer, 2001, p. 460). In recent years, a great deal of popular and empirical attention has been paid to women who earn more than their husbands. Cross-sectional data indicate that wives earn more than their husbands in 20 to 30% of dual-earner couples (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2007; Winkler, 1998) and, when defined as wives’ earning at least 60% of the total income, between 10 and 12% of all couples (Raley et al., 2006; Winslow-Bowe, 2009) in a given year. The percentage of wives earning more than their husbands has increased in recent years. Among all couples, the percentage of majority or sole earner wives more than tripled between 1970 and 2001, from 3.7% to 12.1% (Raley et al., 2006). Data on dual-earner couples indicates a slightly less dramatic, although still substantial, rise—from 18% in 1987 to 25% in 2003 (BLS, 2007). Although the bulk of research on wives’ income advantage utilizes cross-sectional data, recent research indicates that this obscures a sizeable amount of fluctuation in couples’ relative income over a period of several years. Winslow-Bowe (2006) finds that, although 16.3 per cent of women earn more than their husbands in a single year, considerably fewer—5.7 per cent—do so for five consecutive years.1 Similarly, Winkler et al. (2005) find that 40% of women who earn more than their husbands in a given year do not maintain that advantage over a three-year period. These data point to the importance of studying couples’ earnings arrangements as they develop and fluctuate over time. In fact, in their analyses of female MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 205 breadwinner families, in which they distinguish wives with a persistent income advantage from those with a more temporary one, Drago et al. (2005) argue that “the inclusion of the temporary group in studies of female breadwinning will therefore tend to introduce substantial statistical noise into the results” (p. 359). The contribution of this manuscript is two-fold. First, I assess the theoretical and empirical claims of previous research on the shape of the cross-sectional relationship between wives’ relative income and marital duration utilizing data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Second, I expand on previous research by examining whether or not this relationship can be adequately assessed using cross-sectional data. Specifically, I apply existing theoretical and empirical assertions about the shape of the relationship between wives’ earnings and marital conflict to an analysis of panel data, focusing on the impact of the duration of wives’ income advantage over a period of five consecutive years. In doing so, I provide a methodological clarification by separating those wives who temporarily earn more than their husbands from those for whom an earnings advantage is persistent. In short, while existing research has either utilized cross-sectional data (Furdyna et al., 2008; Ono, 1998) or limited its focus to a single shift in earnings dynamics across a two-year period (Rogers and DeBoer, 2001; Schoen et al., 2006; Teachman, 2010), I present the first set of analyses that make full use of panel data by acknowledging the dynamic nature of wives’ income advantage and examining its relationship to marital conflict. WIVES’ INCOME AND MARITAL QUALITY AND STABILITY Marital quality includes satisfaction, happiness, interaction, adjustment, disagreement, and the likelihood of separation or divorce (Spanier and Lewis, 1980; see also Fincfiam and Bradbury, 1987; Johnson et al., 1986), while marital instability encompasses “the gamut of activities from thinking about and discussing divorce to actually filing for either separation or divorce” (Booth et al., 1984, p. 567). The analyses presented here focus on marital conflict, operationalized as the frequency of arguments over a number of key issues. While many analyses have focused on divorce as the outcome of interest, I focus on marital conflict for two main reasons. First, wives’ earnings may have a destabilizing effect even in couples that remain intact. It is thus instructive to examine the relationship between couples’ relative income and subjective reports of marital quality; divorce is, after all, an extreme manifestation of marital 206 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY conflict. Second, Furdyna et al. (2008) argue that controlling for marital quality in research on income and divorce, as is typically done, “may obfuscate an important pathway by which divorce occurs – that is, through the effect of relative income on marital quality” (p. 333). Previous research indicates four potential relationships between a wife’s income, particularly her income relative to that of her husband, and marital conflict: (1) a positive relationship (or independence effect), in which wives’ earnings are associated with greater conflict; (2) a negative relationship (or income effect), in which wives’ income is associated with less conflict or instability; (3) a U-shaped relationship, in which conflict is lowest among couples with relatively equal earnings; and (4) an inverted U-shaped relationship, in which conflict is greatest when partners have similar earnings (see also Rogers, 2004). A substantial amount of theory and research argues for an independence effect of wives’ income. That is, wives’ employment and earnings destabilize marriage, decreasing marital quality and increasing marital conflict. A number of these arguments are couched in the logic of gender-differentiated specialization in marriage. Neoclassical economic theory, as elaborated by Becker (1991) maintains that men and women in families maximize efficiency and utility by rationally specializing in the domain in which each has a comparative advantage—paid labor for men and childcare and household labor for women. Women’s employment reduces specialization, thus making households less efficient and more prone to instability. Parsonian functionalism similarly advocates specialization, with husbands carrying out what he termed the “instrumental” role of income production and wives engaging in integrative and “expressive” activities, as a functional necessity for the maintenance of marriage (Parsons, 1949). While neoclassical economics and functionalism focus on employment more generally, others have argued that earnings, particularly wives’ earnings in relation to those of their husbands, are related to marital conflict. Economic bargaining models argue that the partner with higher earnings is more likely to get his or her way in decision-making situations. Earnings enhance one’s power within marriage specifically because they are portable outside of any particular marriage, unlike investments in household labor, which are more relationship-specific (England and Kilbourne, 1990). Wives’ earning are thus disruptive of marital life because they shift the genderdifferentiated balance of power in marriage by giving wives’ greater decision-making leverage within the relationship and greater opportunities MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 207 outside the marriage. Both, according to this perspective, increase conflict and instability. Empirical analyses offer support for the independence effect of wives’ employment. Trends at the aggregate level suggest a positive relationship between women’s employment and marital instability in that divorce rates rose at the same time as women’s labor force participation rate increased (BLS, 2009; Cherlin, 1992; Clarke, 1995). Analyses at the individual level also provide some empirical support for the independence effect. Vannoy and Philliber (1992) argue that wives’ reports of marital quality are lower when their occupational status exceeds that of their husbands. Perry-Jenkins and Folk (1994) find that, among couples in which both spouses work full-time in “middle class” occupations, the proportion of income contributed by the wife is positively related to her (but not his) reports of marital conflict, while Rogers and DeBoer (2001) find that increases in women’s relative income are associated with a decrease in men’s individual well-being. The latter relationship persists even when controlling for men’s spells of unemployment and declines in their own income, suggesting that the result isn’t simply due to a decline in men’s economic position in and of itself. Others link wives’ earnings directly to divorce. Rogers (2004) concludes that wives’ actual income is positively and linearly associated with the risk of divorce. Teachman (2010) specifies the relationship further, arguing that both wives’ absolute and relative income increases the risk of divorce for Whites. Wives’ earnings appear to be less disruptive to marriage among Blacks, although when controlling for education, Black women who consistently earn more than 60 per cent of the family income are more likely to experience divorce (Teachman, 2010). While much of the theoretical and empirical literature has focused on the independence effect of wives’ earnings on marital disruption, wives’ earnings may decrease marital conflict and instability by raising overall income and thus increasing couples’ quality of life (also known as an income effect). Oppenheimer (1997) argues that breadwinner-homemaker specialization is increasingly risky while two incomes offer protection against economic uncertainty and financial instability. Women’s employment and income may therefore stabilize marriage, rather than having the destabilizing effect predicted by bargaining or specialization models. Indeed, there is empirical evidence to support a negative relationship between wives’ earnings and marital conflict. Rogers and DeBoer (2001) find that increases in wives’ absolute and relative income 208 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY between two points in time are associated with increases in their individual well-being and marital happiness. Similarly, Rogers (1996) finds that, in remarried couples with three or more children, mothers’ full-time employment is associated with lower levels of marital conflict. Finally, Schoen et al. (2006) report that while changes in wives’ employment are not significantly related to changes in marital quality, wives’ becoming or remaining employed full time decreases the likelihood of union dissolution. A third possibility is that the relationship between wives’ income and marital conflict takes the form of a U-shaped curve. Much of the theoretical and empirical research in this area has utilized wives’ proportional (or relative) income as the earnings measure, arguing that conflict is lowest when husbands and wives have relatively equal earnings and highest when wives’ proportional contributions are either very high or very low. This perspective, labeled role collaboration by Rogers (2004), posits that earnings similarity is associated with similar experiences and greater collaboration; similarity and collaboration increase affection and decrease conflict. While less research has focused on curvilinear relationships than on either positive or negative relationships between wives’ earnings and marital quality and instability, there is some empirical evidence for a U-shaped curve. Ono (1998) finds that, controlling for husbands’ income, the risk of divorce is highest when wives either have no earnings or high earnings. Kalmijn et al. (2007) find a U-shaped relationship between women’s relative income and relationship dissolution for cohabitors only; movement away from equality toward either male or female breadwinning increases the risk of dissolution for cohabitors. Finally, a number of studies have suggested that the relationship between wives’ earnings—in particular, their relative earnings—and marital conflict takes the form of an inverted U-shaped curve. That is, conflict is highest when spouses’ earnings are relatively equal and lowest when either the husband or the wife earns the majority of the total income. On the one hand, this perspective is consistent with the argument posited by proponents of specialization—that couples maximize efficiency when one partner retains primary responsibility for breadwinning. However, as reviewed above, classic articulations of this model (e.g. Becker, 1991; Parsons, 1949) emphasize gender-based specialization, with husbands maintaining primary responsibility for economic provision. In contrast, those who argue for an inverted U-shaped relationship between relative MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 209 earnings and marital conflict, which Rogers (2004) refers to as equal dependence, posit that marital instability is lowest when one partner earns the majority of the couple’s total earnings because this is when mutual obligations are highest—regardless of whether the primary earner is the husband or the wife. In contrast, when partners’ earnings are relatively equal, each is less dependent on the other and instability is highest. Scholars examining the relationship between wives’ percentage contributions to total income and marital conflict have offered a number of potential explanations for this relationship. Rogers (2004) argues that, while in couples characterized by specialization (whether traditional or reverse), marital roles are more clear, equal resources may require more monitoring and negotiation. Furdyna et al. (2008) link earnings more explicitly to power, arguing that variation in marital happiness across income ratios “may reflect distinctions between having substantial authority to negotiate roles in the household economy, having no authority or bargaining power, and occupying a more liminal state (not dependent, but not in control)” (p. 342). Indeed, there is empirical support for an inverted U-shaped relationship between wives’ relative earnings and marital instability. Rogers and DeBoer (2001) find that declines in husbands’ well-being are most pronounced when their wives earn between 40 and 50 per cent of the couples’ total earnings. Heckert et al. (1998) find that couples in which the wife earns between 50 and 75 per cent of household income are substantially more likely to divorce than are other couples. Similarly, Rogers (2004) concludes that, for couples with low or moderate levels of marital happiness, the probability of divorce is highest when the wife contributes between 40 and 50 per cent of the total income. The analyses presented here test the assertions of each of the above perspectives on the relationship between wives’ relative income and marital conflict using both cross-sectional and panel data. In my analyses of panel data, instead of using wives’ percentage contributions as the key explanatory measure, I focus on the duration of wives’ income advantage over a period of five consecutive years, thus further expanding on previous research. To summarize, there are four potential relationships between the duration of wives’ income advantage and marital conflict: (1) a positive relationship, in which conflict increases with each additional year a wife earns more than her husband (such that the highest level of conflict ought to be found among those women who consistently earn more than their husbands and the lowest among those who never earn more); (2) a negative 210 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY relationship, in which conflict ought to be lowest among those couples in which the wife consistently earns more and highest among those in which she never earns more; (3) a U-shaped relationship, in which conflict is highest among those couples in which the wife never, rarely, or persistently earns more and lowest among those couples in which the husband and wife share the primary earner role over a period of years; or (4) an inverted U-shaped relationship, in which conflict is lowest among those couples in which either the husband or the wife persistently earns more and highest among those couple in which the husband and wife share the primary earner role over a period of years. DATA AND METHODS The analyses utilize the 1990–1994 waves of the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth a national probability sample of young women and men living in the United States and born between January 1, 1957, and December 31, 1964. The original sample of 12,686 men and women was interviewed annually between from 1979 to 1994 and has been interviewed biennially since 1994. Single-year analyses focus on the 1994 wave of data collection (N = 2261); longitudinal analyses examine the 1990 – 1994 waves of the NLSY79 (N = 1422). The analyses presented here utilize data from the 1990 - 1994 waves of the NLSY79 for two reasons2: (1) 1990 was the first year in which the youngest members of this cohort reached the age of 25, a cut-off used in previous analyses of wives’ income advantage as signaling the beginning of peak labor force participation years (Raley et al., 2006; Winkler et al., 2005) and (2) the NLSY79 became a biennial survey after 1994, thus making yearly fluctuations in income impossible to determine for latter years.3 The sample includes both first marriages and remarriages4 and is restricted to those consistently married to the same partner for the longitudinal analyses.5 Analyses of marital conflict are restricted to female respondents only because the survey questions used as indicators of marital conflict were only asked of women in the sample (see Rogers (1996) for precedent; see also Perry-Jenkins and Folk (1994) for the effects of earnings on women’s reports of marital conflict). DEPENDENT VARIABLE: MARITAL CONFLICT The present analyses focus on the relationship between the duration of wives’ income advantage and marital conflict. The analyses assess conflict over nine key issues—household labor, money, showing affection, MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 211 religion, leisure time, drinking, other women, and both partners’ relatives (separately).6 Specifically, measures of conflict are obtained from female respondents’ answers to the following questions (respondents were asked about each area separately): “How frequently do you and [your husband/ partner] have arguments about [chores and responsibilities, money, showing affection, religion, leisure time, drinking, other women, his relatives, her relatives]?” Respondents answered using the following four category options: “never,” “hardly ever,” “sometimes,” and “often” (measured on a 0 to 3 scale). The analyses presented here use a summed total of each respondent’s answers to these nine questions (see Morrison and Coiro (1999) for precedent); the scale thus ranges from 0 to 27. This measure has an alpha reliability of .74 for single-year analyses and .75 for longitudinal analyses. Both the cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses utilize reports of marital conflict collected during the 1994 wave. Independent Variable: Husbands’ and Wives’ Relative Income I use husbands’ and wives’ wage and salary income to compute a measure of wives’ income as a percentage of couples’ total income for each wave of data (i.e. 1990–1994). For single-year analyses, the 1994 data are utilized to create a number of measures of wives’ relative earnings. • Wife’s per cent of couple’s total income. This is a continuous measure of a wife’s income as a per cent of the couple’s total income in 1994. • Wife earns more than 50% of couple’s income (wife income advantage). The percentage measure above is used to construct a dummy variable of wives’ income advantage. This variable is coded ‘1’ if the wife earns more than 50 per cent of a couple’s total income in 1994, ‘0’ otherwise (i.e. less than or equal to 50 per cent). • Relative earnings categories. In order to assess the U-shaped and inverted U-shaped relationships proposed by previous empirical and theoretical research, I utilize the percentage measure of wives’ income contributions to create a three-category measure of husbands’ and wives’ relative earnings. More specifically, respondents are categorized as being in a couple in which the wife earns less than 40 per cent of the couple’s total income (neotraditional or reverse specialization), the wife earns at least 40 but less than 60 per cent of the couple’s total income (mutual 212 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY dependence, co-provider), or the wife earns 60 per cent or more of the couple’s total income (reverse specialization). This measure reflects that utilized in previous research (Raley et al., 2006; Winslow-Bowe, 2009). For multi-year analyses, I utilize wives’ percentage of couples’ total income to construct a dummy variable of wives’ income advantage for each wave. This variable is coded ‘1’ if the wife earns more than 50 per cent of a couple’s total income in a given year, ‘0’ otherwise (i.e. less than or equal to 50 per cent). This series of single-year dummies is used to create several measures of wives’ long-term income advantage. • Number of years a wife earns more than her husband. This is a summed total of the dummy variables of wives’ singleyear advantage for each wave of data and thus ranges from 0 to 5. It is included in regression models as both a continuous variable. • Three-category measure of wife’s income advantage. A final measure takes the entire five-year time span as a reference point and categorizes respondents as being part of a couple in which the wife earns 50 per cent or more of the total income (1) never or for one year, (2) for two or three years, or (3) for four or five years. This measure thus groups together those who have a relatively stable division of earnings (with one category each for an advantage favoring wives and an advantage favoring husbands) and those for whom relative earnings are in flux (see Drago et al., 2005; Winkler et al., 2005; Winslow-Bowe, 2006 for discussions of the transience and permanence of wives’ income advantage). This is similar to the three-category classification utilized in single-year analyses and allows for the consideration of U-shaped relationships. Control Variables Brief descriptions of all control variables appear below. 7 Marital happiness. Overall marital happiness is based on responses (in 1994) to the question, “Would you say that your [relationship/marriage] is very happy, fairly happy, or not too happy?” While others have used similar measures as a dependent variable, I use it as a control variable because (a) the vast majority (approximately three-quarters) of respondents report that they are “very happy” with their marriages, thus leaving little variation to analyze and (b) Sayer and Bianchi (2000) convincingly MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 213 demonstrate that relationship quality mediates the negative relationship between wives’ relative income and the odds of divorce. The measure of marital happiness is included in the regression analyses as a dummy variable measuring unhappiness; it is coded ‘1’ if respondents reported a relationship that is fairly happy or not too happy, ‘0’ otherwise. Descriptive analyses (Table 1) present a mean measure of marital happiness for which “not too happy” was coded as ‘1,’ “fairly happy” was coded as ‘2,’ and “very happy” was coded as ‘3.’ Race/ethnicity. This variable measures the race/ethnicity of the focal respondent; respondents are classified as non-Black, non-Hispanic, also referred to as White and used as the reference category; Black; or Hispanic. This measure is the main NLSY79 race/ethnicity variable. Husband’s income in bottom quartile. In order to assess whether any disruption caused by wives’ income advantage is conditioned by the necessity of her income, I include a variable measuring whether a husband’s income was in the bottom income quartile of men’s earnings. In single-year analyses this is included as a dummy variable, while in multi-year analyses this is included as a continuous variable measuring the number of years that a husband’s income fell in the bottom quartile of men’s earnings. Husband’s weekly employment hours. In single-year analyses, this measure represent the number of hours per week a husband spent engaged in paid labor. In multi-year analyses, hours worked represents husbands’ average weekly hours worked over the five-year time span.8 Husband’s and wife’s education. Each spouse’s education is measured using a dummy variable indicating whether or not he or she has a Bachelor’s degree or more education (coded as 1; those with less than a Bachelor’s degree are coded as 0).9 Parental status. This measure is designed to capture both the presence and age of the youngest child in the household. Respondents are coded as having no children (the reference category), having a youngest child under the age of six 6, or having a youngest child between the ages of 6 and 17. In multi-year analyses, parental status is measured in the first year of the five-year period (1990), with an additional control for the birth of a child (see below). Birth of a child. This variable is coded 1 if a respondent experienced the birth of a child between 1990 and 1994, 0 otherwise (see Cowan and Cowan (2007) for a discussion of the disruptions associated with the transition to parenthood). 214 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY RESULTS Table 1 presents means and frequencies for all measures in the analyses. I focus my discussion here on the independent and dependent measures— wives’ income advantage and marital conflict. The mean level of marital conflict in 1994 is 7.58; in the multi-year sample, it is 7.74. To put these figures in substantive terms, it is instructive to consider that each of the nine areas of conflict is measured on a 0 to 3 scale, with ‘0’ indicating that they “never” argue over a given topic, ‘1’ indicating that they “hardly ever” argue, ‘2’ indicating “sometimes” arguing, and ‘3’ indicating “often” arguing. This means that the mean level of conflict nears an average of “hardly ever” for respondents in this sample (in that scores of 7.58 and 7.74 on a nine-item measure is an average of just under one for each measure). Table 1 also echoes the results of the growing body of research on husbands’ and wives’ relative earnings and wives’ income advantage. On average, women earn approximately one-third of couples’ total income. Approximately one-fifth of wives (21.8 per cent) earn more than their husbands in a single year and women out earn their husbands in just under one year out of five. Sixty per cent of couples are characterized by traditional specialization in a single year, while just over one-quarter are mutually economically dependent and approximately 13 per cent exhibit reverse specialization. When attention shifts to wives’ long-term income advantage, over three-quarters of women either never ear more than their husbands or do so for only one year (two-thirds, or 66.42 per cent, never earn more). The income advantage fluctuates across spouses in approximately 10 per cent of couples, while 12.36 per cent of women persistently earn more than their husbands. Table 2 explores the relationship between three measures of wives’ single-year relative earnings and marital conflict through OLS regression analyses.10 I present only the final full models including all covariates as successive nested models produced no changes in the substantive results. In addition, because the relationship between marital conflict and the control variables is consistent across models, I first focus on the measures of wives’ earnings, followed by a discussion of the control variables. The most notable finding in Table 2 is that wives’ relative earnings—whether operationalized as a continuous measure of wives’ percentage of couples’ total income (Model 1), a dummy measure of wives’ single-year income advantage (Model 2), or a three-category measure of spouses’ relative earnings (Model 3)—are not significantly associated with reported levels MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 215 Table 1 Weighted Means and Frequencies of all Measures. Source: 1990- 1994 NLSY79 1994 Marital conflict Wife’s per cent of couple’s income Wife earns more > 50% of couple’s total income Relative earnings categories Traditional specialization (wife earns <40%) Mutual dependence (wife earns 40 – 59.9%) Reverse specialization (wife earns> 60%) Years wife earns > 50% of total Wife earns > 50% of total: Never or once Temporarily (2 – 3 years) Persistently (4 – 5 years) Marital happiness ‘Not too’ or ‘fairly’ happy with relationship Race/Ethnicity White Black Hispanic Husband’s income in bottom quartile (yes/ever) Years husband’s income in bottom quartile Husband’s hours worked Wife college educated Husband college educated Parental status Children <6 Children 6-17 No children <18 Birth of a child N 1990 – 1994 Mean Frequency Mean 7.58 32.60 7.74 Frequency 21.80 60.88 26.35 12.76 0.93 77.25 10.40 12.36 2.72 2.73 25.13 24.57 87.81 6.56 5.63 89.82 5.23 4.95 26.38 40.64 1.19 43.88 44.50 2261 50.12 47.45 51.13 47.66 49.67 33.10 17.23 58.17 17.35 24.45 38.34 1422 216 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY of marital conflict. Other results presented in Table 2 indicate that women who report being ‘not too’ or ‘fairly’ happy with their marriages report higher levels of conflict than do women who are ‘very’ happy with their marriages. Analyses not shown tested the potential mediating effect of marital unhappiness on the relationship between conflict and wives’ relative income—while unhappiness itself is a significant predictor of conflict, it does not significantly impact the relationship between wives’ income and marital conflict. Black women report higher levels of marital conflict than do White women. College-educated women and women with college-educated husbands report less conflict than do women whose husbands have less than a Bachelor’s degree, while women with children under the age of six report greater conflict than do women without children under the age of 18. Table 2 Single-year Ordinary Least Squares Regression Analyses of Conflict Source: 1994 NLSY79 Model 1 Wife’s per cent of couple’s income Wife earns more than 50% of total income Relative earnings categories Traditional specialization Mutual dependence Reverse specialization ‘Not too’ or ‘fairly’ happy with relationship Race/Ethnicity White (reference) Black Hispanic Husband’s income in bottom quartile Husband’s hours worked Wife college educated Husband college educated Parental status Children <6 Children 6-17 No children <18 (reference) Adjusted R2 Model 2 Model 3 0.001 0.222 3.520** 3.522** 0.042 -0.031 3.519** 0.651** -0.055 0.255 0.0001 -0.329† -0.678** 0.649** -0.043 0.185 0.003 -0.346† -0.686** 0.648** -0.060 0.283 -0.0001 -0.325† -0.673** 0.801** -0.002 0.819** 0.016 0.797** -0.001 0.167 0.167 0.166 †p<.10. *p < .05. **p < .01. In sum, contrary to the predictions of each of the four perspectives reviewed above, the results presented in Table 2 indicate no significant MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 217 relationship—positive, negative, or curvilinear—between wives’ singleyear relative earnings and reported levels of marital conflict. But what about over a period of several years? Are relative earnings and wives’ income advantage felt cumulatively rather than immediately? Table 3 addresses this issue by examining the relationship between the duration of wives’ income advantage and marital conflict. Table 3 presents ordinary least squares regression analyses designed to assess the four potential relationships between the duration of wives’ income advantage and marital conflict suggested by previous research. As was the case in Table 2, I present full models containing all covariates because, in stepwise models not shown, the relationship between the income advantage measures and marital conflict was not substantively altered by the inclusion of covariates. This includes marital unhappiness— contrary to the predictions of some previous research, marital unhappiness does not mediate the relationship between wives’ long-term income advantage and marital conflict. Because the control variables operate similarly in both models, I first summarize the impact of the two key measures of wives’ earnings advantage, followed by a general discussion of the relationship between the control variables and marital conflict. Model 1 focuses on a continuous measure of the number of years a wife earns more than her husband and is designed primarily to test the income effect—which predicts a linear, negative relationships between the duration of wives’ income advantage and marital conflict—and the independence effect—which predicts a linear, positive relationship between marital conflict and the number of years a wife earns more than her husband. Contrary to either of these predictions, the continuous measure of the length of wives’ income advantage is not significantly related to reported levels of marital conflict. Model 2 focuses on a categorical measure of the number of years a woman earns more than her husband, classifying women as earning more than their husbands never or for one year only, for two or three years, or for four or five years. In addition to offering another test of the income and independence effects, this categorical measure allows for an examination of U-shaped relationships. The results indicate that women who earn more than their husbands for two or three years out of five— that is, couples in which the income advantage fluctuates across partners over a period of years—report higher levels of marital conflict than do those who never earn more than their husbands or do so for only one year. Those who persistently earn more than their husbands report levels 218 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY Table 3 Ordinary Least Squares Regression Analyses of Conflict, by Wives’ Long-term Income Advantage. Source: 1990- 1994 NLSY79 Model 1 Years wife earns > 50% of total Wife earns > 50% of total Never or once (reference) Temporarily (2 – 3 years) Persistently (4 – 5 years) ‘Not too’ or ‘fairly’ happy with relationship Race/Ethnicity White (reference) Black Hispanic Years husband’s income in bottom quartile Husband’s hours worked Wife college educated Husband college educated Parental status Children <6 Children 6-17 No children <18 (reference) Birth of a child Adjusted R2 Model 2 0.088 3.547** 0.896* 0.479 3.555** 0.234 -0.130 0.062 0.027* -0.527* -0.690* 0.262 -0.102 0.032 0.027* -0.541* -0.709** 0.148 -0.329 0.183 -0.301 0.851** 0.171 0.862** 0.173 of marital conflict that are not significantly different from those who never earn more or do so for only one year. Across all models of Table 2, those who are “not too” or “fairly” happy with their marriages report significantly greater marital conflict than do those who are happy with their marriages. Husbands’ work hours are associated with higher levels of marital conflict, while husbands’ and wives’ college educations are associated with lower reported levels of conflict. Finally, measures of parental status at the beginning of the time interval under consideration are not significantly associated with marital conflict—parents, regardless of the age of the youngest child in the household, do not report significantly different levels of conflict than do those without children in the home. Those who experienced the birth of a child during the interval considered in the analyses, on the other hand, report significantly greater marital conflict than those who did not add a child to their family. MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 219 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION Two major findings stand out. First, comparing the analyses of crosssectional and panel data indicates that a full understanding of the relationship between marital conflict and wives’ relative earnings, particularly their income advantage, cannot be gleaned from crosssectional data, nor from longitudinal analyses that measure only a single change in couples’ relative income. In fact, the cross-sectional data indicate no significant relationship between wives’ income relative to that of their husbands, regardless of the operationalization of this measure, and marital conflict. Moreover, analyses of panel data indicate that attention to fluctuation in couples’ relative earnings is key. Thus, research on the relationship between marital conflict and husbands’ and wives’ relative income must utilize panel data and take into account the results of recent research indicating that wives’ income advantage is often temporary rather than persistent (Winkler et al., 2005; Winslow-Bowe, 2006). Second, the longitudinal analyses offer support for the assertions of a mutual dependence perspective—marital conflict is highest when the income advantage fluctuates across spouses over a period of five years. That is, the relationship between marital conflict and the duration of wives’ income advantage takes the form of an inverted U-shaped curve. More specifically, conflict is highest among those couples in which the wife out earns her husband for two or three years out of five (and, by extension, a husband out earns his wife for the other two or three years). I find no support for an independence effect, income effect, or U-shaped relationship (i.e. role collaboration). In other words, marital conflict does not increase or decrease linearly as the years a wife earns more than her husband increase, as would be predicted by the independence and income effect perspectives, respectively. Nor does a shared income advantage over a period of years increase similarity and affection, as the role collaboration perspective would predict. Why might such fluctuation be disruptive? Two related strands of theoretical and empirical research suggest potential answers. West and Zimmerman’s (1987) formulation of gender as a routine accomplishment of everyday behavior and interaction is useful in understanding the impact of fluctuation in wives’ income advantage. According to West and Zimmerman (1987), individuals engage in behaviors that construct gender and thus appropriately locate themselves in their respective sex category— they “do gender.” Applying this approach to household labor activities, they write, “It is not simply that household labor is designated as ‘women’s 220 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY work,’ but that for a woman to engage in it and a man not to engage in it is to draw on and exhibit the ‘essential nature’ of each. What is produced and reproduced is not merely the activity and artifact of domestic life, but the material embodiment of wifely and husbandly roles, and derivatively, of womanly and manly conduct” (West and Zimmerman, 1987, p. 144). While West and Zimmerman use the example of housework, one could easily apply the same logic to economic provision. In other words, husbands’ primary earning, an activity intricately linked to the husband role, draws on and exhibits their “essential nature.” Fluctuation in husbands’ and wives’ income advantage is disruptive because it inhibits the ability of each to exhibit their “essential natures” and perform “wifely and husbandly roles.” To do gender appropriately, West and Zimmerman (1987) note, we must do it consistently. Couples in which the income advantage fluctuates operate under structural conditions in which this is impossible (at least as far as wage earning is concerned). The implicit assumptions set forth by West and Zimmerman’s (1987) articulation of doing gender are made more explicit by another vein of symbolic interactionist theory. Identity theorists argue that individuals strive for self-verification—that is, situations in which one’s perceptions of oneself match the identity standard he or she has established (Stryker and Burke, 2000). When there is a mismatch between the situational perception and the identity standard, individuals attempt to produce alignment (Stryker and Burke, 2000). Identity modification is a gradual process in which either (1) behavior is modified to change situational perceptions or (2) the identity standard slowly shifts so as to more closely match situational perceptions. Two key points are relevant to the topic at hand. First, identity change, though pervasive, is small and slow (Burke, 2006). Burke (2006) writes, “Because this process is slow, it is unlikely to result in much change unless the perceptions are persistently different from the standard” (p. 93). Second, aligning perceptions with standards through behavioral modification is not always possible. In many situations, individual behaviors are constrained by structural exigencies (e.g. the economy). These structural realities have the potential to disrupt “the continuously adjusting identity processes” (Burke, 1991, p. 840). The product of this disruption is distress (Burke, 1991), which Stets and Burke (2005) show can lead to aggression in marriage. To apply this to the current analyses, an identity theorist would argue that the roles of husband and wife carry with them particular expectations. MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 221 These expectations shape one’s identity standard. For example, as would be predicted by much of the research on gender in marriage, one’s identity as a wife may involve caretaking and nurturing but not acting as the primary earner in the household. One’s identity as a husband, in contrast, may quite likely hinge on fulfilling the breadwinning role (for an application to fatherhood, see Townsend (2002)). Primary earning on the part of a wife, then, produces a situational perception that does not align with the identity standard of either spouse. Identity theorists would argue that both spouses would work to create alignment between perceptions and standards by altering identity standards (e.g. by adding wage earning to one’s definition of the wife identity) or modifying the situation. Both alternatives are problematic. On the one hand, one’s salary is largely determined by outside forces outside of one’s control, thus creating structural barriers to modifying the situation. Thus the remaining alternative is to adjust one’s identity standard to include, to a greater or lesser extent, the role of primary earner. As reviewed above, such change is ubiquitous but slow. Women with a persistent income advantage have the opportunity to move through this process of identity change, incorporating greater responsibility for wage earning into their identity standard with each year that they out earn their husbands. Over time, then, the identity standard of those with a persistent income advantage aligns with situational perceptions. Women in couples in which the income advantage fluctuates (and, by extension, their husbands), on the other hand, are less able to adapt their identity standards to include responsibility for wage earning because the perception of themselves as primary earner (derived from the realities of situation) is not consistent. The mismatch between situational perceptions and identity standards thus continues, producing stress that manifests itself in marital conflict. In sum, the analyses presented here add to the literature on the impact of wives’ employment on family life by utilizing panel data to understand how the duration of wives’ income advantage is related to marital conflict. I find no indication that wives’ single-year income advantage is significantly related to reported levels of marital conflict. Moreover, persistent income advantages on the part of either husbands or wives do not appear to be disruptive. Instead, reported levels of marital conflict are highest among couples in which the income advantage fluctuates across partners over a period of years. In these couples, mutual obligations are lowest and the role of primary earner is contested terrain and this—not who bears this title—is a source of conflict. 222 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY Notes 1. These analyses utilize the 1990–1994 waves of the NLSY79, the same data used in the analyses that follow. 2. The cross-sectional analyses use 1994 as the focal year because questions regarding relationship dynamics were only asked in the 1988, 1992, and 1994-2006 waves of data collection. 3. Analyses not shown indicate that the prevalence and persistence of wives’ income advantage among this restricted sample do not significantly differ from other, broader samples, suggesting that the results presented here are unlikely to be substantially shaped by the cohort and year restrictions imposed. 4. In analyses not presented, a control for marital order in multivariate analyses indicated that remarriages do not differ significantly from first marriages. This control is not included in the final presented models. 5. Analyses not shown indicate little evidence for a relationship between wives’ income advantage and sample attrition. 6. While the NLSY79 also contains a measure of the frequency of conflict over children, this is excluded from the analyses because this question is necessarily only asked of parents, thus artificially inflating the level of conflict reported by some members of the sample. However, in analyses not presented, all models were run using a measure of total conflict including conflict over children. All substantive results were similar to those presented here, including all relationships between wives’ income advantage and marital conflict. The analyses here can be taken as a conservative estimate of the impact of children on marital conflict, insofar as children are themselves another arena of potential conflict. 7. In analyses not presented, controls for wife’s age, marital order, and marital duration were included; these measures were not significantly related to marital conflict, nor did they influence any of the substantive results. In the interest of parsimony, these are not included in the final presented models. 8. Measures of wives’ weekly work hours are not included as they are highly correlated with wives’ income. 9. Additional analyses utilizing a multi-category education measure yielded substantively similar results; thus, the simpler dummy variable is included in the analyses presented below. This manner of measuring educational attainment is similar to that utilized in other research (see, for example, Goldstein and Kenney, 2001) demonstrating diverging family experiences by education. 10. Since it could be argued that the dependent variable is categorical (in that it was constructed from a series of ordered categorical responses), all models MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 223 (cross-sectional and longitudinal) were also run using cumulative ordered regression. In addition, analyses were conducted on subsets of the dependent variable (e.g. arguments over chores and money, the two most frequently reported areas of conflict, only) and utilizing unordered logit estimation techniques. In all cases, the substantive results remained the same, thus the simpler single OLS model is presented here. References Becker, G. S. (1991). Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Booth, A., Johnson, D. R., White, L., & Edwards, J. N. (1984). Women, Outside Employment, and Marital Instability. The American Journal of Sociology, 90(3), 567-583. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2007). Women in the Labor Force: A Databook [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-databook-2007.pdf Bureau of Labor Statistics (2009). Women in the Labor Force: A Databook [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-databook-2009.pdf. Burke, P. J. (1991). Identity Processes and Social Stress. American Sociological Review, 56: 836-849. Burke, P. J. (2006). Identity Change. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(1), 81-96. Cherlin, A. (1992). Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Clarke, S. C. (1995). Advance Report of Final Divorce Statistics, 1989 and 1990. In National Center for Health Statistics, Monthly vital Statistics Report, 53(9, Supplement). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/mvsr/supp/ mv43_09s.pdf Cowan, P., & Cowan, C. P. (2007). New Families: Modern Couples as New Pioneers. In A. S. Skolnick & J. H. Skolnick (Eds.), Family in Transition (14th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. Drago, R., Black, D., & Wooden, M. (2005). Female Breadwinner Families. Journal of Sociology, 41(4), 343-362. England, P., & Kilbourne, B. (1990). Markets, Marriage, and other Mates: The Problem of Power. In R. Friedland & S. Robertson (Eds.), Beyond the Marketplace: Society and Economy. New York, NY: Aldine. Fincfiam, F. D., & Bradbury, T. N. (1987). The Assessment of Marital Quality: A Reevaluation. Journal of Marriage & Family, 49(4), 797-809. Furdyna, H. E., Tucker, M. B., & James, A. D. (2008). Relative Spousal Earnings and Marital Happiness among African American and White Women. Journal of Marriage & Family, 70(2), 332-344. 224 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY Hartmann, H. (1976). Capitalism, Patriarchy, and Job Segregation by Sex. In Blaxall, M., & Reagan, B. (Eds.), Women and the Workplace: The Implications of Occupational Segregation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Heckert, D. A, Nowak, T. C., & Snyder, K. A. (1998). The Impact of Husbands’ and Wives’ Relative Earnings in Marital Disruption. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 690-703. Johnson, D. R., White, L. K., Edwards, J. N., & Booth, A. (1986). Dimensions of Marital Quality: Toward Methodological and Conceptual Refinement. Journal of Family Issues, 7(1), 31-49. Kalmijn, M., Loeve, A., & Manting, D. (2007). Income Dynamics in Couples and the Dissolution of Marriage and Cohabitation. Demography, 44(1), 159179. Morrison, D. R., & Coiro, M. J. (1999). Parental Conflict and Marital Disruption: Do Children Benefit when High-conflict Marriages are Dissolved? Journal of Marriage and Family, 61(3), 626-637. Ono, H. (1998). Husbands’ and Wives’ Resources and Marital Dissolution. Journal of Marriage and Family, 60(3), 674-689. Oppenheimer, V. K. (1997). Women’s Employment and the Gain to Marriage: The Specialization and Trading Model. Annual Review of Sociology, 23, 431453. Parsons, T. (1949). The Social Structure of the Family. In R. Anshen (Ed.), The Family: Its Function and Destiny (pp. 173-201). New York, NY: Harper. Perry-Jenkins, M., & Folk, K. (1994). Class, Couples, and Conflict: Effects of the Division of Labor on Assessments of Marriage in Dual-earner Families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 165-180. Raley, S., Mattingly, M., & Bianchi, S. (2006). How Dual are Dual-income Couples? Documenting Change from 1970 to 2001. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(1), 11-28. Rogers, S. J. (1996). Mothers’ Work Hours and Marital Quality: Variations by Family Structure and Family Size. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58(3), 606-617. Rogers, S. J. (2004). Dollars, Dependency, and Divorce: Four Perspectives on the Role of Wives’ Income. Journal of Marriage & Family, 66(1), 59-74. Rogers, S. J., & Deboer, D. D. (2001). Changes in Wives’ Income: Effects on Marital Happiness, Psychological Well-being, and the Risk of Divorce. Journal of Marriage & Family, 63(2), 458–472. Sayer, L. C., & Bianchi, S. M. (2000). Women’s Economic Independence and the Probability of Divorce: A Review and Reexamination. Journal of Family Issues, 21(7), 906-943. MARITAL CONFLICT AND THE DURATION OF WIVES INCOME ADVANTAGE 225 Schoen, R., Rogers, S. J., & Amato, P. R. (2006). Wives’ Employment and Spouses’ Marital Happiness. Journal of Family Issues, 27(4), 506-528. Sorensen, A., & McLanahan, S. (1987). Married Women’s Economic Dependency, 1940-1980. American Journal of Sociology, 93(3), 659-687. Spanier, G. B., & Lewis, R. A. (1980). Marital Quality: A Review of the Seventies. Journal of Marriage and Family, 42(4), 825-839. Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2005). Identity Verification, Control, and Aggression in Marriage. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(2), 160-178. Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 284-297. Teachman, J. (2010). Wives’ Economic Resources and Risk of Divorce. Journal of Family Issues, 31(10), 1305-1323. Townsend, N. (2002). The Package Deal: Marriage, Work, and Fatherhood in Men’s Lives. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. Vannoy, D., & Philliber, W. W. (1992). “Wife’s Employment and Quality of Marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54, 387-398. West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing Gender. Gender and Society, 1, 125-148. White, L. K. (1990). Determinants of Divorce: A Review of Research in the Eighties. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 904-912. Winkler, A. E. (1998). Earnings of Husbands and Wives in Dual-earner Families. Monthly Labor Review, (April), 42-48. Winkler, A. E., McBride, T. D., & Andrews, C. (2005). Wives Who Outearn their Husbands: A Transitory or Persistent Phenomenon for Couples? Demography, 42, 523-535. Winslow-Bowe, S. (2006). The Persistence of Wives’ Income Advantage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(November), 824-842. Winslow-Bowe, S. (2009). Husbands’ and Wives’ Relative Earnings: Exploring Variation by Race, Human Capital, Labor Supply, and Life Stage. Journal of Family Issues, 30(10), 1405-1432.