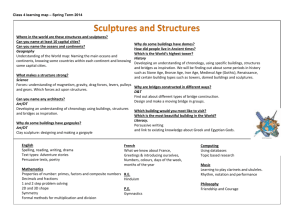

meaning of “building” in the depreciation rules

advertisement