newsletter, winter 2013 - Hertfordshire Geological Society

advertisement

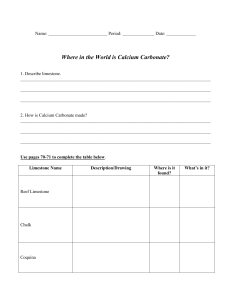

NEWSLETTER, WINTER 2013 FIELD TRIP TO BULMER BRICK AND TILE WORKS, ALPHAMSTONE AND LITTLE MAPLESTEAD, SATURDAY JUNE 23, 2012 By Lesley Exton A plant sale and coffee morning taking place down the road meant the parking facilities at the works were in demand. After making sure we were all parked up safely, the owner Peter Minter started with a brief run through of the 500+ year history of brick making on the site. In that time it has only been owned by three different families. His father, a builder took it over in 1936. Then in September 1939 the government had all the kilns in Britain put out because their roofs glowed when they were alight. Many didn’t start up again after the end of WWII. At Bulmer all their younger workers were called up, however, they were able to retain the older men so he learnt all the old techniques from them as a youngster. The business survived by making land drain pipes for farms and airfields. When his father died in 1974, the works were in a very dilapidated state, it has survived by staying specialist. Fig. 1. The group in the quarry at Bulmer listening to Peter Minter. [Photo: Lesley Exton] 1 They were approached by English Heritage in the 1970’s as Hampton Court couldn’t find anyone who could supply what was required for some restoration work. Now, 90% of their work is made to order, eg. they did all decorative brickwork for the arches in the St Pancras station extension (the original material came from Sudbury – the 19th C builders had sourced all their materials using the Midland Railway lines). They have 150 different brick styles and over 7000 patterns with more added all the time. No other brickyard uses this specific type of London clay, which matches most alluvial clays from Somerset to York. However, their largest market is London & East Anglia. He then walked us round the site and through the process. It starts with the drawing of a template and then making up the box mould, which has to allow for the 12% shrinkage that occurs. We then went into the building where the clay is washed and pressed and examined the machines used. They can get two presses of clay a day. The resulting product is then left to stand for a couple of weeks. From there we went into the quarry to look at the face (fig. 1) and the piles of different grades of clay already dug out, which came from different areas of the face. They take off the top one metre (3 ft) (Lambeth ash) then dig down four metres (12 ft), then refill. They dig a year’s worth (1 000 tons) out in a single session and it is used as required. They do bring clay in from other areas, eg. Burwell, usually to blend; which is done in an old bath at the entrance to the quarry. The clay piles keep for about two years until oxidation alters the consistency so then they would also be blended. Fig 2. Stacked bricks drying at Bulmer Brick and Tile Works. [Photo: Nick Pierpoint] They usually make about 10% over per order to allow for breakages. The bricks are then stacked to dry (up to 8 rows high) (fig. 2). How long this takes depends on the weather, in March they were drying within a week but since April they’ve been taking six weeks. Each 2 order is stacked separately. Currently they are stacked outside, but from October they are artificially dried in storage sheds. They are then stacked in the kiln. Their final colour depends on their position in the kiln, light at the bottom, dark at the top. They built a new kiln as the old one was becoming unsafe, but couldn’t afford to use their own bricks! It is a free dome structure, built without supports and the roof is done in a herring bone pattern, filled with brick earth. It took two weeks to build the new kiln (fig. 3), then they dismantled the old one and rebuilt it in a week. This was to stop it getting a preservation order put on it which would have caused problems in a working yard, however, it also doubled their capacity as they now have two working kilns. Firing takes three days, one day to build up the heat (950° at the bottom - 1150° at the top), then two days to actually fire the bricks. The whole process actually takes over a week, as it takes two and a half to three days to load the kiln and then another two and a half days to unload it once it has cooled down. We then looked at some of the finished products, including bat bricks – with six slots per brick for roosting bats and bricks for a bell foundry which would be used during casting process. Finally, we had a look at some of the larger moulds actually in use which are built in sections and then slot into a larger frame so they are much lighter than if they were made in one piece. Fig.3. The new kiln Bulmer Brick and Tile Works. [Photo: Lesley Exton] After lunch, taken either at the Victory Inn or in the village green bus shelter, we negotiated a very narrow single track lane to get to St Barnabus church, Alphamstone. There we examined the sarsens in and around the churchyard, and found a few more than were plotted on the map in the handout. This could have been because the greenery had been recently cut back rather drastically. They are unusual because the eastern counties are not rich in megalithic sites. If they are of prehistoric origin then this would carry on the venerable tradition of churches being located on earlier Neolithic sites. We then continued onto our final stop, Little Maplestead church. This is only one of four 3 round churches still standing in England, the others being in London, Cambridge and Northampton. The latter two are parish churches, but this one was built by the Military Religious Order of the Knights Templars and the one in London by the Military Religious Order of the Knights Hospitallers. The design was probably based on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. We were able to go inside, which was a welcome respite from the cold wind, however, the problems with damp were very obvious. A more scenic route was on offer for the return journey for the more adventurous of the party. FLINT KNAPPING EXPERIENCE, MAIDSCROSS HILL NATURE RESERVE AND GRIMES GRAVES, SATURDAY 14 JULY 2012 By Nikki Edwards Twenty two people from the HGS and the EHGC met up at the Brandon Country Park Visitor Centre, Suffolk, to meet John Lord, master flint knapper and wife Val. They brought along a very impressive display of genuine Palaeolithic tools which Val handed round for us all to see (fig. 4) as well as very large tabulate flint to be knapped (fig. 5). The tools that John used – antler hammers, punchers and flaker, quartzite hammer stone and a hide palm pad, were the kind of tools that must have been used thousands of years ago. The technological terminology was decidedly modern. John took great care to impress us that any attempt to produce one’s own tools must be undertaken with great care in terms of personal safety and also to deal with the debritage so that anyone finding it in the future would not be lead misguidedly into thinking that they had discovered an historic site. Fig. 4. Val Lord showing the group some genuine Palaeolithic tools. [Photo: Lesley Exton] 4 . Figs. 5 & 6. John Lord, with tabulate flint and the hand axe produced. [Photos: Lesley Exton] His demonstration was fascinating, with the rationale for each step explained. As well as the end product of a large hand axe (figs. 6 & 7), smaller flakes were shaped for a variety of uses (fig. 7): His demonstration was fascinating, with the rationale for each step explained. Fig.7. The different tools produced. [Photo: Lesley Exton] 5 After a tasty lunch at the Visitor Centre restaurant or in your car if you’d brought sandwiches, as it had started to rain, we travelled the few miles to Maidscross Hill Local Nature Reserve. This is a 50 hectares remnant of Brecks heathland and was opened in July 2004, after funding by Lottery money. Tim Holt-Wilson, a local geologist and naturalist, gave an outline of the Breckland heath landscape, pointing out salient features from the high vantage point. The site overlooked a runway at Lakenheath Airbase, and the lack of aircraft activity was a minor disappointment. Another short drive took us to Grimes Graves, the only Neolithic flint mine open to visitors in Britain. This grassy lunar landscape of 400 pits was first named Grim’s Graves by the Anglo-Saxons. It was not until one of the ‘graves’ was excavated in 1870 that they were identified as flint mines dug over 5,000 years ago. The visitor centre had a small exhibition area illustrating the history of this fascinating site. Everyone braved the nine metre (30 ft) descent by ladder into one excavated shaft to see the jet-black flint. The chalk section present in the main shaft includes at least six flint bands and it is one of the lowest of these, the so-called Floorstone flint, which was the main target for the flint miners. This substantial tabular flint lies close to the base of the traditional “Upper” Chalk, within the Burnham Chalk Formation. The whole section sits just above the local equivalent to the Reed Marl (seen in Hertfordshire) and is therefore of Upper Turonian age. Set amid the distinctive Breckland heathland, Grime’s Graves is also a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and a habitat for rare plants and fauna. The combination of chalk grassland that resulted from the mining activity, sandy heath and acid grassland supports a wide range of unusual plants, which are encouraged by continued sheep and rabbit grazing. Tim Holt-Wilson continued his explanation of the area, in particular, the periglacial stripes of alternate light and dark vegetation to the north of the site. THE CRAVEN INLIERS OF THE SW YORKSHIRE DALES, SEPTEMBER 27-30, 2012 By Linda Hamling, with help from Clive Maton Friday, September 28. After a night in Prestwich we travelled in Bobby's luxury coach to Helwith Bridge from where we had a panoramic view of Ribblesdale. We were standing in one of the Craven inliers, windows that afford us the opportunity to study the Silurian and Ordovician rocks upon which the impressive limestone above lies. Glaciation in the Quaternary cut down into these Lower Palaeozoic rocks leaving Ribblesdale as a glaciated valley. To the west, in the hillside of Moughton, were two quarries cutting into the youngest of the Silurian basement rocks, the Horton Formation. The rock was originally used for roofing slates but nowadays it is crushed for roadstone. This is of very high quality as it doesn't polish nor abrade badly in use. Some is coated in bitumen on site. The beds in Dry Rigg Quarry dipped to the north whereas those in Arcow Quarry dipped to the south there being a syncline between. Above the Silurian is the Great Scar Limestone. The sub-horizontal limestone, which is some 50 million years younger than the Silurian, lies unconformably on the steeply dipping Horton Formation beneath. We climbed up beside Dry Rigg Quarry to where we could see down into it. The working 6 face is 250m high and there is potential for 60m more of extraction. The National Park Authority restricts the annual extraction rate. The dip is 40 into the syncline and it was pressure from this folding which resulted in the cleavage making it suitable for slates, although of poor quality. Further from the fold axis the dip gets steeper. Also the finer beds deform into parasitic folds in response to the pressure called layer parallel shortening. Moughton Nab is a prominent landscape feature which can be recognised from a great distance. It is a large notch at the base of the Great Scar Limestone which projects some 2m. above Dry Rigg Quarry. We collected samples from the scree below it and found them to be of a dark, strongly crystalline limestone. This was a bioclastic deposit with impurities which have imparted the dark colour but pressure has caused it to crystallise which has removed most of the fossils. This is the Kilnsey Limestone, the lowermost of the three notable limestones which comprise the Great Scar Limestone. We climbed up to the overhang to see the limestone in situ. A beautiful Lithostrotion colonial coral was found in the face (fig. 8). At the base of the limestone there was no basal conglomerate indicating deposition in a low energy environment and below we found two small exposures of the unconformity with the Horton Formation. Fig. 8. Lithostrotion colonial coral in the Kilney limestone. [Photo: Lesley Exton] Moving on up through a narrow rocky path in the face of the scar we came upon a scree slope from where a much lighter, hence purer limestone was collected. Other than in colour it was very similar to the Kilnsey Limestone. Named after Malham Cove, this is the Cove Limestone. It is less competent than the Kilnsey Limestone and as such, the beds being thinner, gives rise to a stepped landscape. Few scars are of this limestone. A very pure (98% CaCO3) porcellanous limestone bed is found near the top of it. 7 Cresting the rise we overlooked a large solution doline with Long Scar beyond. We were standing on till on which acid loving plants grew. By contrast the limestone supported lush green grass. Long Scar is of Goredale Limestone, the third of the Great Scar Limestones. This is a more competent limestone with a similar colour to Cove but a larger grain size. It is likely that this is the reason that only the Goredale Limestone forms good limestone pavements. By now it was lunchtime and, it being very windy, we sheltered and picnicked in subsidence dolines of which there were several. They came in very useful! After lunch it started pouring with rain as we climbed up on to the Goredale Limestone pavement. We picked our way very gingerly across it balancing on the wet clints (fig. 9). Ferns, Hawthorn and Herb Robert grew within the shelter of the grykes. The angle of direction of the grykes was measured as 320 indicating tectonic stress at 050. The limestone was gently folded into an anticline, dipping at 10 to 12 in both directions, arising from the Variscan Orogeny and thus not the result of the same folding as in the Silurian beneath. We turned north following a wall which separated shooting land from grazing land. Junipers grew here. We had an expansive view northwards. To the east we could see Pen-y-ghent, a hill capped and protected by Millstone Grit as were Ingleborough and Whernside to the west. Beneath is the Yoredale Series above Great Scar Limestone. A small fault on the pavement to the east of where we were standing had influenced the drainage pattern. Fig. 9. The group crossing the Goredale Limestone pavement. [Photo: Lesley Exton] We walked to look into Foredale Quarry. It is an abandoned quarry still showing signs of the trackways used to carry away the quarried rock. Then we climbed down to Combs Quarry where the unconformity between the Limestone and the Silurian was well displayed in the back wall (fig. 10). A thin bentonite bed formed from tuff is found here. From here a bog 8 could be seen adjacent to Dry Rigg Quarry. This is Swarth Bog, an important SSSI a nearly complete raised peat bog formed on top of a glacially derived depression. Fig. 10. Unconformity between the limestone and the Silurian. [Photo: Lesley Exton] We descended into the east-west running valley to the south of Moughton and discussed the evidence for it being formed when the glacier in Ribblesdale was diverted by a blockage. Key evidence was observed towards the west where there is a steep sided wooded gorge, Wharfe Gill, indicating a glacial overflow channel. We could see Goredale Limestone across the valley at a lower level down-thrown by the North Craven Fault which runs along the south side of the valley indicated by a change in slope. Another change in slope indicates a fault, the Wharfe Fault, which pre-dates the North Craven Fault, having been formed deep in the Lower Palaeozoic. That evening we ate at the Game Cock Inn in Austwick where we enjoyed French cuisine and the company of a lovely friendly cat. Saturday September 29. The next morning we drove past Giggleswick Scar. This fault line scarp is an impressive expression in the landscape of the line of the South Craven Fault. We started our walk just outside of Austwick where we were able to look back to where we had been the day before by looking along the valley south of Moughton. Moughton Nab was easily identifiable as was Wharfe Gill. The wooded gorge contains Wharfe Gill Sike, a misfit stream which forms a 30m waterfall at the head of Wharfe Gill where it passes over the competent Austwick Formation and Wharfe Fault to flow into the weaker strata of the Norber Formation which is older by approximately 13 million years. We were standing on the south side of an anticline, on Jop Ridding Sandstone, on a lithic arenite arising from an epiclastic mass flow from the Lake District, outcrops of which could be seen in the distance abutting the North Craven Fault. Moving on we went to look at Robin 9 Proctor Scar. This is of Cove Limestone, as we were on the north side of the North Craven Fault, with Kilnsey Limestone beneath. The hillside to the north displayed interruptions as slopes in the face which denoted smaller faults associated with the main Craven Fault. The limestone pavement we were on at 225m was darker in colour being the Hawes Limestone, the first of the post Great Scar Limestones. The Goredale Limestone above Robin Proctor Scar has a height of 408m giving us an indication of the 250-300m throw at this end of the fault system. We passed by a bog which had formed on the till. Its surface was traversed by a pale line in the vegetation marking the line of the fault. The compass gave a reading of 294 for the North Craven Fault as opposed to 320 from the grykes yesterday showing strike slip movement due to the deformation in the Variscan Orogeny after the normal faulting in the Carboniferous. We climbed up to overlook the line of the North Craven Fault in the landscape stretching out before us along the valley south of Moughton. To the south of that we observed the Feizor Fault and then the South Craven Fault picked out by Giggleswick Scar in the distance. Fig. 11. The group with a Norber erratic in Crummack Dale. [Photo: Haydon Bailey] The Norber erratics are named after the field in which they are mainly found (fig. 11). There are about 1000 of them up to 26 tons or more in weight. They are a medium grained sandstone whose beds vary in resistance. Their cleavage and bedding directions have led to them being cuboid in shape. They are Silurian in age and yet are sitting on younger Carboniferous Cove Limestone having been brought here by ice. Protection of the limestone beneath them from dissolution and weathering has led to some being stranded on pedestals whose height may indicate the rate of erosion and weathering since the last ice age. They haven't been moved far and we were to see their origin later on. A family was trying to fly their kite in the strong wind as we walked to inspect a cliff of Kilnsey Limestone, Nappa Scar. Beneath quite massive limestone was a conglomeratic bed and then a debris flow. By scrambling along a sheep track below the footpath we were able to study a basal cross stratified conglomerate within which were fossils including brachiopods. Bobby found two corals. This deposit was formed in a high energy environment with well rounded small pebbles and by offshore limestone being broken up by wave action and being thrown up on to a palaeobeach. Then there was a debris flow followed by another transgression giving rise to another conglomerate, then quiescence allowing the formation of the Kilnsey Limestone. At the junction between the limestone and basement a spring issued 10 forth denoting an unconformity where the water meets the impermeable Upper Ordovician Shales beneath. The spring is intermittent, flowing only for 48 hours after any rain has ceased. We reached the road where we were able to examine the type section of the Norber Formation, a rather nondescript exposure at the bottom of the road bank (fig. 12). It displayed a fine grained calcareous distal deposit with fossils of which we saw part of a trilobite and brachiopods. It had very strong cleavage which could be confused with the bedding which is difficult to identify. Fig. 12. Clive in front of the type section of the Norber Formation. [Photo: Lesley Exton] Braving a bull with his heifers we made our way across fields in Crummack Dale. The Norber Formation is at the centre of the Nappa anticline we've crossed and so we should have then come upon the Ordovician Jop Ridding Sandstone again but that mass flow was localised and instead there was interbedded sandstone and tuffs. The Sowerthwaite Formation was hidden from view by till but looking back the Norber Formation could be seen as a linear hummock running east-west. It limited the flow of erratics. We then crossed the Wharfe Fault which we had observed earlier. This was to be a walk complicated by folding and faulting. We came upon the Crummack Formation, dark grey and graptolitic, as we got closer and closer to the closure of the syncline which crossed the valley here causing the beds to come together. We then sat ourselves down on the source rock (not the source point) of the Norber erratics. We confirmed that indeed the rock was the same as that of the erratics. This was the lower beds of the Silurian Austwick Formation called by Clive the Crummack Lane Sandstone. The outcrop curved from here to the actual source point on the other side of the road. Erratics could be seen littering the area. 11 The exposure of this formation was scarred by glacial striations. Further on holes in the rock from where clasts had been eroded were imbricated giving an idea of the direction of this turbidite flow towards the north (fig 13). Fig. 13. Holes left after clasts have been eroded out. [Photo: Lesley Exton] While the beds mostly dipped north some dipped south before dipping north again there being parasitic folds on the limbs of this major syncline. At the Wash Dub sheep were dipped in Austwick Beck in times past. We crossed over the stream on a clapper bridge to follow a green lane between stone walls. Over a stile a little waterfall tumbled over the fold axis of the syncline, the beds of the rocks dipping into the stream bed on either side. Clive told us of the Moughton Whetstone further on but which we had no time to visit. A sandstone used in the past as whetstone, it is attractively stained by red and green Liesegang Rings. We walked back to emerge above Wharfe where we studied an exposure of the upper beds of the Wharfe Sandstone. This displays a classic bouma sequence with impressive flute casts on a basal surface. Very noisy sparrows greeted us in the hamlet of Wharfe as did Bobby with the coach. Sunday September 30. We met in the car park at the Ingleton Waterfalls Walk where Clive explained that this day we would cross both the North and South Craven Faults and so we were full of anticipation in spite of the bad weather. The Faults were active in the Carboniferous when the Great Scar Limestone was being laid down. South of the South Craven Fault the Goredale beds are thicker because the deposition was concurrent with the faulting. If the faulting had occurred after deposition then the bed thickness would be the same either side of the fault. 12 Here we were on an alluvial terrace above Coal Measures with Millstone Grit below. Ingleton had had a small working coalfield and overhead were the remains of the railway serving the mine. We started out following the course of the River Twiss bloated by the ever present rain. It wasn't far along the walk that we crossed the South Craven Fault. We entered Swilla Glen, a narrow gorge which had originally been carved out by glacial meltwater. Here the beds of Goredale Limestone were dipping south having been offset by the North Craven Fault. Torrential dark peaty water rushed through the gorge. At the top of the precipitous cliff on the other side of the river was till of which more later. We came upon a fallen tree which had been completely studded with coins by tourists dating back to Victorian times for this valley has been a tourist attraction ever since then. We then saw that the beds in the river bank opposite were now dipping near horizontal suggesting that this was an anticline. Further on, in an exposure by the path, the beds were now dipping north. There is indeed an anticline, the Helks Anticline, between the South and North Craven Faults implying strike-slip movement in the faults during the Variscan Orogeny. We stepped on to Manor Bridge to look down the swollen river along the length of which the North Craven Fault runs. Hence as we looked back there was Goredale Limestone as a large cliff, the fault plane, but here, on the eastern side, we were now on Palaeozoic Norber Formation. In the opposite bank there was an adit, an attempt to mine lead but it was not productive. Below was a side fault and now we were fully in the Palaeozoic, the Goredale having been downthrown by the North Craven Fault. We found the contact between the younger Ordovician Norber Formation and the older Pecca Formation there being a gap of 30 million years in age between them owing probably to a fault but some people have suggested it is an angular unconformity. The Pecca Formation is very slatey having been very strongly deformed. All these Lower Ordovician rocks are on the Skinwith Syncline. This was much steeper than that at Crummack and so the deposits were laid down in deep water, raised, eroded and gently folded and, at the end of the Silurian, refolded. Tufa clothed the cliff wall further on and so above there must be limestone for the source of this calcareous deposit. Some of us scrambled up into Pecca Quarry where the steeply dipping slatey rocks were seen to have been overthrown by a parasitic fold. The bedding and cleavage were very difficult to distinguish from each other. On reaching the tea hut, which stands on the syncline, the beds were found to dip south indicating that this is an isoclinal fold. Thornton Force was in full spate owing to all the recent rain (fig. 14). It was a very dramatic sight. Its size was put in perspective by walkers who were dwarfed as they climbed up the steps beside the falls. The river poured over a shelf of horizontal Kilnsey Limestone. At the base of the limestone was a basal conglomerate lying unconformably on rocks of the steeply angled Pecca Formation. The Pecca Formation, being of less resistant siltstones and mudstones, has been and is being eroded back at a faster rate than the overlying limestone forming an overhang. A huge block of the limestone lay in the plunge pool having fallen there after the rocks beneath had been eaten away. It looked like it could have happened recently; however, a reproduction of a J.M.W. Turner sketch done in 1816 on the information 13 board showed it had lain there for at least 200 years. Water sprang forth from beneath the limestone on encountering the impermeable Pecca Formation. Clive scrambled down to show us a lamprophyre dyke, associated with melting of rocks during the Caledonian Orogeny in the Devonian, which had been intruded into these rocks. Fig. 14. Water cascading over Thornton Force. [Photo: Lesley Exton] Till coated the hillside. Its deposition as a terminal moraine in Kingsdale impeded the flow of the river and diverted its course creating Thornton Force and leaving a buried channel under the till. We picnicked on soggy sandwiches here whilst we enjoyed the grandeur of the falls. We returned to cream teas in the cafe while our clothes dripped all over its floor. It had been a grand day in every sense despite the relentless rain. Everyone had thoroughly enjoyed the weekend thanks to Clive for his clear explanation of the geology and his field guide, to Haydon for his organisation and Bobby for his comfortable coach and careful driving and his enthusiastic interest in our activities. John Hepworth (1919-2012) By John Catt One of our previous presidents, John Hepworth, died in the Lister Hospital in Stevenage on January 15th 2012 aged 92. He was president from 1996 to 1998, during which time he faithfully attended almost all of our meetings, bringing humour and an amazing breadth of knowledge to discussions in the field and lecture room. John was born in Southport, Lancashire on November 29th 1919, and after serving in the army during World 14 War II he studied geology at Bristol University, where he graduated with First Class Honours. In 1951 he joined the Colonial Geological Survey and was sent to Uganda for field mapping in various parts of that country including the Western Rift. This work was published as numerous maps and reports, and a geochemical and petrographic study of the rocks of the rift was submitted as a PhD thesis at Leeds University. During the 1960s, John worked at the Colonial Survey’s Photogeology Division in London, mainly investigating parts of Mozambique and Tanzania. He was then appointed Director of the Botswana Geological Survey (1971-1974), and was subsequently (1975-1980) Regional Geologist for Asia in the Overseas Division of the Institute of Geological Sciences (now British Geological Survey). In the last position, he supervised exploration for coal in Kalimantan and major mapping projects in Thailand and Sumatra. Finally (1980-1983) he worked for the United Nations in Bandung, editing papers written by geologists employed by the UN in southeast Asia whose first language was not English. Fig. 15. John Hepworth [Photo: Angela Hepworth] John joined the Geological Society of London in 1950, and was a member of its Council for many years and Foreign Secretary from 1975 to 1978. In the early 1970s he and other young members of Council became unhappy with the Society’s old-fashioned methods of operation. They formed the ‘Kardomah Group’, so-called because it met to discuss strategy before and after each Council meeting at the Kardomah Café opposite Burlington House in Piccadilly. Pressure from the Kardomah Group was the main force instrumental in changing the Society from ‘a fuddy-duddy London-based clique into a national society’. He was also an active member of the Geologists’ Association, regularly attending its lecture and field meetings. John married his third wife, Angela, in 1979. They lived at Dominic Cottage close to St Nicholas Church in Stevenage, where Angela was churchwarden for five years. John tolerated but never shared her enthusiasm for Christianity and the Anglican church, and he remained a professed atheist even in his final illness. At the same time she tolerated but was never converted by his boundless enthusiasm for geology. One interest they did share was the need to protect from major housing development the attractive rolling countryside north of Stevenage, made famous by the local novelist E.M. Forster. Together with Margaret Ashby, John co-founded in 1989 a pressure group known as The Friends of Forster Country, 15 which was remarkably effective in preserving this beautiful part of Hertfordshire, and is still active today. Appropriately it was on a cold and snowy day in January that John was finally laid to rest close to Dominic Cottage in the Weston Road Cemetery, which provides a magnificent view over the Forster Country he did so much to preserve. Following his retirement in 1983 John acquired an interest in local silcretes (puddingstone and sarsen) and the geomorphology of the Chalk landscape in southern England. This resulted in memorable HGS field excursions on the Chilterns and Salisbury Plain. It also drove him to organize a personal field visit to Australia, where he could study recent silcretes at first hand, and then to write his final scientific paper (Aspects of English silcretes and comparison with some Australian occurrences. Proc. Geol. Ass. 109 (1998), 271-288). An enthusiastic geologist to the end, John will be remembered partly for his professional approach to geology, but mainly for his kindly support and quiet advice to amateurs and younger members of the profession. CHAIRMAN’S CONCLUDING REMARKS By Haydon Bailey It’s been a busy year and geologically and the pace shows little sign of slowing, so let’s review where we’ve been and more importantly where we’re going. We’ve seen and heard a whole series of fascinating presentations through the year, frequently outside my own Cretaceous comfort zone, which have educated and enlightened us geologically. The programme for 2013 is already looking diverse and stimulating, which is how it should be. Our field visits have been remarkably good and my thanks go to Linda for the organisation of the trip to the Bulmer Brick and Tile works and to Nikki for locating our singular flint knapping guide, John Lord, as well as arranging for us to visit Grimes Graves on the same day. Nikki also organised a geological walk for us around Sherrardswood led by Richard Bateman which took place on a gloriously sunny Spring day. All these days in the open have been enjoyable and well worth being part of. Our sincere thanks also go to Clive for his masterminding of the excellent weekend trip to the Yorkshire Dales. The geology was stunning and despite the worst the weather could throw at us, we could at least say that we tested our wet-weather gear to the maximum. It was a memorable trip for a variety of reasons, for the good company, the Norber erratics and for the opportunity to extend our geological interests well down into the Palaeozoic. I think the suggestion that next year we head to the Devon coast is made on the basis of the geology rather than the potentially better weather. Finally, we hope to see increasing co-operation and liaison with our neighbouring geological societies over the next year two, with programme sharing and possible joint field meetings. We have some good friends locally and we share some fascinating geology so all the more reason for getting together and enjoying it. 16