American Social Contract - National Academy of Social Insurance

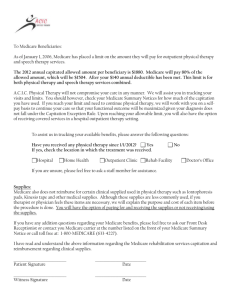

advertisement