Sacred Fire Booklet

advertisement

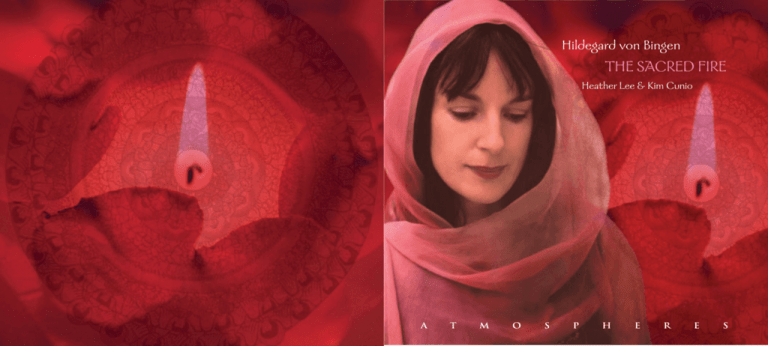

Hildegard von Bingen THE SACRED FIRE Heather Lee & Kim Cunio A T M O S P H E R E S The Sacred Fire A new realisation of the music of Hildegard of Bingen And it came to pass in the eleven hundred and forty-first year of the incarnation of Jesus Christ, Son of God, when I was forty-two years and seven months old, that the heavens were opened and a blinding light of exceptional brilliance flowed through my entire brain. And so it kindled my whole heart and breast like a flame, not burning but warming. (HILDEGARD VON BINGEN, Scivias) Hildegard of Bingen was an undoubted visionary. She had transcendental experiences throughout her life, and these experiences informed her worship and her sense of the world. In the medieval environment, it was seen as possible to have a direct link with the angels and the Holy Spirit; and it is this sense of wonder that The Sacred Fire seeks to explore. In the last decade there have been many recordings of the music of Hildegard, ranging from the historically informed works of ensembles such as Sequentia, to a number of adventurous fusion recordings that have sought to combine this wonderful music with all sorts of modern sounds. The Sacred Fire is both of these. It is faithful in a historical sense, but is also musically adventurous. This is not the flippant adventure of those who combine a keyboard or hastily composed chord scheme with the original music, but the result of an exacting realisation process. Left | Hildegard von Bingen, Nine Ranks of Angels 2 3 Hildegard’s life Hildegard’s life is momentous for the quality and diversity of her work in the spheres of natural history, medicine, cosmology, music and poetry at a time when most educated women rarely wrote Alongside this realm of practical worship, Hildegard had visionary experiences. These started when she was a child, and were accompanied by many periods of poor health. In 1141 this escalated, giving Hildegard the inspiration to write her first major visionary work, Scivias (Sci Vias Domini, or Know the Ways of the Lord). Her visions pertained to all manner of religious texts and precepts, or acted in the public sphere. Hildegard was born into a rich family, and was not given to the church accompanied by the repeated command: ‘O fragile one, ash of ash, and corruption of corruption, say in the standard manner of becoming a nun, but enclosed, apparently for life, in the cell of an and write what you see and hear.’ anchoress attached to a Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg. This occurred at the age of eight. It was such a radical proposition that it was common for the parents to have a funeral ceremony for the child, whom they would not expect to ever see again. It must have been a profound experience for this child to move into a stone room, to grow into a woman in this small world, accompanied by constant ritual. In her youth Hildegard shared a cell with Jutta. Jutta was the daughter of a nobleman, a worldly-wise and skilled woman who was well versed in the practical skills of reading, writing and singing. As Hildegard’s first biographer and former secretary, the monk Godfrey, wrote: ‘[Jutta] carefully Hildegard soon became known as an expert on theological matters, a remarkable feat for a woman with no formal education. As she became a more public figure, her visions changed in character from being associated with a light, to an ability to understand without any human teaching the writings of the prophets, the evangelists and of other holy men and certain philosophers. While it was still very difficult for women to actively preach and teach, it was possible for them to write, though they usually did so through a male scribe. Moreover Hildegard wrote in Latin, a language that could only be read by the clergy, a language of which she had only a limited mastery. introduced her to the habit of humility and innocence. She taught her the Psalms of David and It is incredible that Hildegard, against the wishes of the Abbot at Disibodenberg, set up a convent for showed her how to give praise on the ten-stringed psaltery’ (Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, Book 1). her order of sisters at Rupertsberg, near Bingen, in 1152. Despite the difficulties of starting a new community, this was a place that greatly increased her creative output, dedicated to the Virgin and As a young woman Hildegard read text and music, and possibly played the stringed psaltery. the Holy Spirit as well as to St Rupert. During this period she wrote a great deal of music, and it Hildegard led a Benedictine life, which had regular prayer times from the middle of the night to the reflected her idea that music should mirror the sound of the heavenly spheres, with her sisters singing following evening, with a strong ethos of keeping the mind and body occupied through work. like angelic choirs. By the time of her death in 1179 Hildegard was a formidable figure in every Jutta was to remain a principal figure in Hildegard’s life, and their small cell became increasingly sphere of life. Her last letter to Abbot Ludwig, in 1174, shows her state of mind clearly: known. Women joined them, and when Hildegard was an adult their cell became more a small Now, put on the armour of heaven like a valiant knight, and wash away the deeds of your foolish youth. convent linked to the nearby monastery. When Jutta died in 1136, Hildegard was seen as the obvious In the angelic vestment of the monk’s habit, labour strenuously at noon, before the day ends, so that you successor to lead this women’s community. will be received joyfully into the company of angels in the heavenly tabernacles. 4 5 Music Hildegard is best known for her Ordo Virtutum (Play of the Virtues), a work which shows many of the elements of modern dramatic poetry and opera. Ordo Virtutum is deeply related to Scivias, her first major theological work, and involves a cast of allegorical characters similar to those in the morality plays which came to be fairly widespread in the Church. Within a biblical idiom Hildegard invented a plot to weave morality, nature and instinct together. In this play the conflicts are between the forces that shape our spiritual destiny. The soul is the Dendermonde, Belgium, and the Riesenkodex, in the collection of the Hessen State Library in Wiesbaden. One important piece in this collection is O vis aeternitatis, the first entry in the Wiesbaden manuscript, written with the notion of profunda altudine (profound height, a term she invented). It encapsulates the mysteries contained in her writing, conveyed through a combination of solo and responsorial singing. These works represent a microcosm of height and change within the history of Church music. Though dedicated to the ideals of purity and reverence to the high godly orders of the Church, they protagonist, affected by The Virtues on one side, and the base world symbolised by The Devil on the also played a part in the disintegration of Church music and modality. Their nature is to change other. Because these forces are personalised, they seem somehow easier to comprehend and more emphasis, to write new melodies not based on the established canon of Gregorian chant, and to direct in nature. The music ends with victory after loss, for the soul initially loses itself to the devil, write mostly for a force composed of women, whose voices had only filled the fringes of the Church’s only then calling for help to the virtues, who aid it and draw it up above, to immortality. In its heart musical history. this music represents Hildegard’s own triumphs. It is easy to forget how radical this must have been in the medieval world. Women were still largely As Barbara Thornton of Sequentia put it: ‘Her creations must be seen as resulting from her personal, seen as a lowly creation of spirit, as having an embodied weakness, or corruption, related to the flesh. mystical experiences of God’s revealed realm, and any musical concept of Ordo Virtutum must Hildegard had faith in the transformative mystical qualities of her order, and her music is empowering acknowledge this astounding proposition.’ as well as transcendental. This is the result of a great sense of identity gained through spiritual As well as this sacred drama, Hildegard set over 70 of her poems to music; these are now known practice and worship, that Hildegard and her sisters must have shared. collectively as Symphonia armoniae caelestium revelationum. Written for her sisters at Rupertsberg, Hildegard wrote 77 pieces of music, all imbued with religious zeal, all relating to liturgical belief. They these pieces were intended to mirror the godliness of the creation on Earth, not in itself a new are in the forms of the day: antiphons, sequences, hymns and responsories. They directly relate to the concept, but embellished by Hildegard in her wish to recreate the sounds of the heavenly spheres (an life Hildegard led, and were used in the worship of her order. The subjects befit her life: the Virgin almost Pythagorean concept), and an angelic choir. Mary, the angels, the Apostles, John the Baptist, the saints, including St Rupert, and the major figures These works were mostly composed between 1151 and 1158, a highly productive period for of God, Jesus Christ and the Holy Ghost. Hildegard during which she also wrote treatises on natural science and the healing arts. The two These works were composed not for a class of professional singer, but for a nun or monastic main sources for her music are a manuscript held in the Abbey of St Peter and St Paul in community singer indoctrinated into the Benedictine philosophies of constant prayer, transformation 6 7 and physical work. Vocal nuance was as natural as possible and the vocal tone in this realisation allowed communication of the textual meaning. This music should be approached with a knowledge of the conventions of Hildegard’s time. Though it is possible to reproduce what Hildegard wrote on the page, a little embellishment is possible, and indeed more in line with what may have actually been heard at the heavenly convent of Rupertsberg. This inspired us to make a new realisation. Realisation A realisation is an artistic process, which seeks to rebuild the music of a given period or time. It is very different to a reconstruction, which comes from the position of having a definitive sound to work with. Literal representations of Hildegard’s music have already been recorded, due to a general consensus as to how her surviving scores should sound. This recording is quite different as it is unashamedly speculative. Most researchers agree that there is no way of knowing whether medieval scores were the end product of the music, or just the beginning. This can be posed as a question: were the neumatic scores of Hildegard’s time an exact replica of what was played, or a clue as to its sound? We can easily ask this question of the Baroque figured bass, the modern song chart, and many other music forms. the officially sanctioned music of Pope Gregory – Gregorian Chant). It consists of one melodic line without the harmony that was starting to develop in Europe at the time, particularly in French musical centres such as Notre Dame. The melodic line in Hildegard’s music is largely sacrosanct and should be treated in a similar manner to other Christian liturgical music. What is less clear is the role of instruments or instrumental music. References are made to the psaltery in the writings of both Hildegard and her scribe Godfrey, and many instruments were played in Hildegard’s time. Performance ensembles have responded to this with a surprising amount of accompaniment and interpretative new composition, something that this project also embraces. A recent example is contained in the Sequentia recordings of Hildegard’s music. Sequentia (founded in 1977) have recorded more of Hildegard’s music than any other ensemble. Such realisations occur in the majority of their recordings. For example the notes on the Elizabeth Gaver realisation in Voice of the Blood speak of a piece ‘weaving together both freely and in a stately structure some of the most tender of Hildegard’s 8th-mode gestures. As this mode in the 12th century was thought to be most indicative of the state of blessedness, bestowing upon the listener inner peace and meditative quiet, its effect is to offer comfort.’ In other words a new piece was written to convey these notions of Hildegard. Realisation is a legitimate process, but in order for such a realisation to be valid it must fulfil a few criteria: Another major question pertains to the vocal sound. Were the women’s voices at Rupertsberg schooled in a modern classical sense? Were they capable of the projection that a modern opera singer can achieve? In both cases the answer is probably no. These were singers who did many other things • It must be played on an instrument of the time, or at least on a related instrument. besides singing. Nevertheless, it can also be argued that the best singers in Europe went to the Church in medieval times, and that the music itself needed a broad technical ability. These women sang a great deal, almost every day, and the performance capabilities of the order must have developed over time. • It must work within the defined modal and melodic relationships of the time. The performance, and in this case the realisation, of Hildegard’s work raises a number of significant points. This music is directly related to the plainchant of the codified Christian liturgy (taken to mean 8 • It must be composed according to the melodic and ornamental precepts of the time and of the original work. • It must be created in full awareness of the process of realisation. After choosing repertoire, a new realisation was written for each piece, leaving space for instrumental lines and countermelody. This led to a consideration of how best to accompany this music. 9 Rhythm and accompaniment There is no way of knowing exactly what the neumes of Hildegard meant to the medieval performer, or what was the exact time duration of the music. All we do know for certain is that the melodies, and some description of their ornamentation, have been preserved. paraphrasing the main motifs or responses of a piece. An example is the realisation of O Ierusalem, where at the end of each responsory section, the last phrase is echoed by the taragotto, which repeats and highlights the cadence. Another device used in this project is the echoing of the main line of a phrase, just after its sounding. This gives an implied harmony, as the two melodies weave together. This is sometimes called word echoing or ghosting. Hildegard’s music unfolded in a free and languid sense of time. There was great fear in the medieval world about the polluting effect of rhythmic music, a concept that originated in the Old Testament, Another important device is the use of suspensions. Suspensions function as decorations of a scale, but which was also prevalent in much ancient writing. A study of later Christian manuscripts shows and they offer the opportunity to illuminate the meaning of a text. The recording of O vis aeternitatis that rhythm did enter Church music, though the process was carefully managed. By the early 13th uses a suspended fourth in many cadences, as well as providing tonal colour by playing the root of century the motet and the conductus had appeared, and the music of composers such as Léonin and the mode, in this case E. Suspensions are placed into the drone accompaniment, providing a melodic Pérotin was receiving great acclaim. Rhythmic modes were invented that placed rhythm firmly into impetus that is always wholly within the mode of the song. Unlike most modern suspensions, these the world of God’s creation. A broad division was made between secular and sacred rhythm. Secular do not resolve to another note. In most modern music, a suspended fourth resolves to a major or music had an imperfect two- or four-beat rhythmic pulse, while the music of the Church was written minor third, a sixth resolves to a fifth, and a ninth resolves to the octave. In this project, suspensions in the pulse of three, which symbolised the Trinity. In The Sacred Fire, rhythm was used on a number of the newly-composed instrumental pieces, though not on the vocal music. A similar process of examination was followed regarding the use of accompaniment. We know that Hildegard wrote wholly within the modes of perfection – the great church modes. The points of stability and consonance in modal melody were the octave, the fourth and the fifth, the intervals that create sustained and beautiful dissonance. Ornamentation When I first sang the antiphons of Hildegard ten years ago with composer Kim Cunio, I was immediately struck by its resonances with some music of the Near East, in particular parts of the Indian subcontinent, Persia and Iraq. This is not a similarity that can be traced through direct lines of best reflected the Godly order on earth – these intervals are known as ‘perfect’ to this day. Hildegard communication, although indirect lines did move from the Arabic world to Al Andalus (the seat of favoured the leap of a fifth for melodic emphasis, after which she would often ascend to an octave Islam in Europe, now in modern Spain), into Europe, where they influenced the great flowering of above the original note. Western secular medieval music. One of the innovations of this project was the use of accompanying phrases. The logical point for It is rather a similarity of ethos, spirit and innovation. Both early Near Eastern music and the music of accompaniment was to provide a respite between vocal lines. In this case it was written by Hildegard radically altered the understanding of what was vocally possible. 10 11 In Hildegard’s case it was the triumph of new composition for the woman’s voice. Her works paid Countermelodies were played by the taragotto, a modern medieval-styled reed instrument, and the homage to the canon of liturgical music, but reworked it to show the woman’s ability and range. This Japanese bamboo flute, the shakuhachi. The choice of players reflected this, and an ensemble of was new music that moved from the comfortable octave range of Gregorian chant, to the wild limits leading traditional players was formed. of the soprano voice. Leaps are commonplace with Hildegard, and her lines move higher and higher, often leaping to the octave or tenth of the scale, a device rarely heard in her time. The range of Hildegard’s music is close to two octaves, and this extended range provides much greater opportunity for virtuosity. Finally harmony was added. Organum, the first great medieval harmonic language, was the only realistic choice. Organum reinforces a melody by having another version of it sung or played either up a fifth or down a fourth. In later times organum was shunned due to a perception of its having a ‘bare’ sound, but in this context it is anything but bare, especially in O Ierusalem and in the choral The culture of melodic embellishment in Near Eastern music informed our realisation process. In sections of Patriarchs, Prophets and Virtues and O ignis spiritus. Texture was also developed in this much Persian and Arabic music, the melodies can seem quite simple at their first listening. What project, something best reflected in the Patriarchs, Prophets and Virtues from Ordo Virtutum. The piece brings them to life is an exquisite sense of subtlety, where many notes in a phrase have their own ends with the choir singing in organum, the soprano voice soaring above it, and the taragotto departures or musical ornaments, which contain their own beauty. playing above voice and choir – another manifestation of the Trinity, a triplum, where three lines work together. The role of text and melody in Near Eastern music is very similar to that of the music of Hildegard. The melody supports the revelation of the text, and is set within a scale that has divine or semi-divine A number of new pieces were written for the project. Some are modal works played by an implications. The great difference is the relationship between melody and time. In Near Eastern music instrumental ensemble, to accompany spoken words from the writings of Hildegard. Others are free and rhythmic time co-exist, and rhythm is something to be delighted in. Our project instrumental pieces realised in different ways. experimented with the relationship between tempo, ornament and rhythm. Many of the pieces on In the case of O beatissime Ruperte, the original vocal line was given to an ensemble of gittern (a this recording are considerably slower than on other recordings. However, the use of Near Eastern medieval plucked-string instrument), reed organ and taragotto. A radical turn was the setting of this ornamental techniques allowed the music a space in which to grow, as in the newly-composed The melody to a three-pulse, kept by the Persian daff, a large frame drum with metal beads. Sacred Fire, which explored ornament itself as the primary mode of melody and accompaniment. New instruments and pieces The choice of instruments reflected and embellished this process. A large percussion kit included a mass of tuned gongs, cymbals and bells. The bowed sounds of the medieval vielle were substituted In Dance of Ecstasy, a new piece was written from a number of modal fragments favoured by Hildegard. This was pure conjecture of what ensembles of the time may have played. In this case the gittern was replaced with a Turkish baglama (a seven-stringed plucked-string instrument with moveable frets). The Iranian zarb was the perfect rhythmic choice. by the kamanche from Persia. A drone was added to many pieces on the Western reed organ, the The Ordo Virtutum medley displayed another process. Audrey Ekdahl Davidson from the Hildegard North Indian harmonium and, on one piece, Caritas abundat, on the South Indian tampurah. Publishing Company wrote a number of small refrains based on Hildegard’s music for inclusion in a 12 13 performance of Ordo Virtutum. These were rewritten in additive rhythm (with each bar given a different time signature). The piece was arranged with a strong homage to South Indian (Carnatic) music, and is played on the tavil, a South Indian temple drum, accompanied an ensemble of organ, CD1 1 O Fragile One 0’57 Hildegard von Bingen, Scivias gittern, taragotto and kamanche. Rebecca Frith voice, Tunji Beier bells These realisations are at their heart an aesthetic statement, an attempt to take us into the soundworld of the Benedictine nun. They use the musical devices of the time in a poetic manner. It is hoped that This is a profound statement of what happened during Hildegard’s life. It placed her as an they complement the work of Hildegard of Bingen, and take us into a space of introspection, a place instrument of God, of service to humanity, despite her frail and weak disposition. A medieval bell where the needs of the soul are addressed. begins the intonation. O fragile one, ash of ash, and corruption of corruption, say and write what you see and hear. Heather Lee Modern editions consulted during this project 2 The Sacred Fire Ekdahl Davidson, Audrey (ed.), Ordo Virtutum Hildegard von Bingen, Bryn Mawr, Hildegard Publishing Company, 1991. Kim Cunio Grant, Stephen, Editions of Hildegard von Bingen, Melbourne, unpublished, 2004. In D Aeolian mode Jeffreys, Catherine, O Ierusalem, Melbourne, unpublished, 1991. 2’18 Heather Lee soprano, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Tim Constable gongs Page, Christopher (ed.), Abbess Hildegard von Bingen Sequences and Hymns, England, Antico Church Music, 1982. Richer, Marianne (ed.), Hildegard von Bingen: Symphonia armoniae caelestium revelationum, Vol I-V, Bryn Mawr, Hildegard Publishing Company, 1991. This newly written piece brings us into the world of this project, and introduces the incredible References small, played between the knees with a loose bow. Delicate lines are passed from voice to the Baird, J. and Ehrman R., The Letters of Hildegard von Bingen, New York, Oxford University Press, 1994. kamanche, and back, with a deep resonance provided by the gongs. Flanagan, Sabina, Hildegard of Bingen: A Visionary Life, London, Routledge, 1989. Flanagan, Sabina, Secrets of God: Writings of Hildegard of Bingen, London, Shambhala, 1996. Thornton, Barbara, ‘Hildegard von Bingen’s Spiritual Compositions’, in Canticles of Ecstasy [CD liner notes], Deutsche Harmonia Mundi 05472 77320 2, 1994. Thornton, Barbara, ‘Ursula and Ecclesia: Myths and Meaning’, in Voice of the Blood [CD liner notes], Deutsche Harmonia Mundi 05472 77346 2, 1995. sound of the Persian kamanche. The kamanche is a four-stringed instrument, very light and 3 O pastor animarum 3’14 Hildegard von Bingen Antiphon for the Creator No. 61. In G Dorian mode Heather Lee soprano, Tim Constable gongs This haunting piece shows the range of Hildegard’s melody. It is a tender plea to the divine for inspiration and intervention in our lives. 14 15 4 O pastor animarum et o prima vox, O Shepherd of souls, you of first voice, perquam omnes creati sumus. by whom we all are fashioned, Nunc tibi placeat ut digneris be willing to liberate us nos liberare de miseriis et languoribus nostris. from our weakness and sadness. 5 O quam mirabilis 6’47 Hildegard von Bingen Antiphon for the Creator, R. fol. 466. In A Mixolydian mode Heather Lee soprano, Bronwyn Kirkpatrick shakuhachi, Kim Cunio harmonium, Tunji Beier cymbals Verse 4’45 O vis aeternitatis O power of eternity, que omnia ordinasti in corde tuo, you who have ordered all things in your heart: per Verbum tuum omnia creata sunt through your word all things are created sicut voluisti, as you have willed, et ipsum Verbum tuum and your word itself induit carnem puts on flesh in formatione illa in the form que educta est de Adam. that is drawn from Adam. O quam mirabilis Oh, how wondrous est prescientia divini pectoris is the prescience of the divine heart que prescivit omnem creaturam. who knew every creature before it was made. Et sic indumenta ipsius And so those garments Nam cum Deus inspexit faciem hominis For when God looked on the face of man a maxima dolore are wiped clean quem formavit omnia opera sua whom he formed, he saw all his works abstersa sunt. by great pain. in eadem forma hominis integra aspexit. complete in that same human form. O quam mirabilis est inspiratio Oh, how wonderful is the holy breath que hominem sic suscitavit. that brought man thus to life. 6 Refrain 7’04 Verse O quam magna est benignitas salvatoris, Oh, how great is the saviour’s kindness, qui omnia liberavit who freed all things per incarnationem suam, by that incarnation Hildegard von Bingen quam divinitas expiravit which divinity breathed out, Antiphon, responsory for the Trinity. R. fol. 466. In Hidden E mode sine vinculo peccati. unchained by sin. O vis aeternitatis [18’18] Heather Lee soprano, Kim Cunio baritone, harmonium, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Paul Jarman taragotto 16 7 Refrain 6’29 Gloria Patri et Filio Glory to the Father and to the Son et Spiritui Sancto. and to the Holy Spirit. 17 8 Ordo Virtutum medley 4’03 Recomposition of Hildegard fragments first recomposed by Audrey Ekdahl Davidson. In E Phrygian mode Kim Cunio reed organ, Llew Kiek gittern, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Paul Jarman taragotto, Tunji Beier tavil Ordo Virtutum, The Play of the Virtues, is probably Hildegard’s most striking work. This medley contains a series of modal fragments derived from Hildegard’s music, rewritten with a number of variations. The rhythm in this piece is additive, freely changing, in the manner of speech, and extensive ornamentation has been added. All instruments play the same tune, though they have different points of emphasis. This piece is a precursor to an indepth exploration of the beginning of Ordo Virtutum in the second disc. And It Came to Pass 5’12 Hildegard von Bingen, Scivias In A Phrygian mode Rebecca Frith voice, Kim Cunio reed organ, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Paul Jarman taragotto, Tunji Beier bells, cymbals And it came to pass in the eleven hundred and forty-first year of the incarnation of Jesus Christ, Son of God, when I was forty-two years and seven months old, that the heavens were opened and a blinding light of exceptional brilliance flowed through my entire brain. And so it kindled my whole heart and breast like a flame, not burning but warming. 18 [15’32] Hildegard von Bingen Sequence for the Holy Spirit. R. fol. 471. In F Aeolian mode Heather Lee soprano, Cantillation chorus, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Kim Cunio harmonium, Paul Virag conductor Kim Cunio 9 O ignis spiritus This masterful work alternates between solo voice and responsory, and in this realisation a modal refrain is added on the kamanche. This piece, like a number of Hildegard’s, is concerned with the great metaphorical fire, and as it moves towards its conclusion the choir moves into organum to further glorify the great fire of light that cuts through all obscurations. 10 Verses I– IV 5’58 O ignis Spiritus Paracliti, vita vite omnis creature, sanctus es vivificando formas. O fire of the Paraclete Spirit, the life in every creature’s life, you are holy in giving life to forms. Sanctus es ungendo periculose fractos; sanctus es tergendo fetida vulnera. You are holy in anointing the dangerously stricken; you are holy in wiping fetid wounds. O spiraculum sanctitatis, O ignis caritatis. O dulcis gustus in pectoribus et infusio cordium in bono odore virtutum. O vent of holiness, O fire of love. O sweet taste in our breast and fragrance of virtues flooding our hearts. O fons purissime, in quo consideratur quod Deus alienos colligit et perditos requirit. O purest of fountains, in whom is shown that God gathers together those who are far, and finds those who are lost. 19 11 Verses V–VIII 5’25 O lorica vite et spes compaginis membrorum omnium et o cingulum honestatis, salva beatos. O breastplate of life and great binding hope to all the members [of Ecclesia]. O sword belt of honour, save the blessed. Custodi eos qui carcerati sunt ab inimico, et solve ligatos, quos divina vis salvare vult. Guard those souls whom the enemy has taken, release all those captives that the divine power wills to save. O iter fortissimum quod penetravit omnia; in altissimis et in terrenis, et in omnibus abyssis tu omnes componis et colligis. O most constant path reaching to the heart of all things; in heaven and earth, and in every abyss you call us all together. De te nubes fluunt, ether volat, lapides humorem habent, aque rivulos educunt, et terra viriditatem sudat. You make the clouds issue forth, and the high airs fly, you give the stones their presence, you bring forth the water’s streams, and make the earth sweat with green things. 12 Verses IX–X 20 Indeed, you always teach the learned, those whom the inspiration of Wisdom has made glad. Unde laus tibi sit, qui es sonus laudis, et gaudium vite, And so all praise be to you, you who are the very sound of praise, and the bliss in life, you who are hope and the greatest honour, giving the gifts of light. 13 O beatissime Ruperte 2’02 Hildegard von Bingen Antiphon for Saint Rupert, R. fol. 471. Recomposed and played as an instrumental piece. In D Aeolian mode Kim Cunio reed organ, Llew Kiek gittern, Paul Jarman taragotto, Tunji Beier daff This piece is one of the radical departures of the project. The antiphon was set to a rhythmic three-pulse, something of which there is no record at the time. The ensemble plays the vocal tune with a sense of acceleration and wonder, to personalise the virtues of this little-known saint who was so inspirational to Hildegard: ‘O great, auspicious Rupert, you who blossomed in life, you who were free from the vice of the devil. You left this pained world, now help us in the memory of God, Alleluia.’ The Persian daff drives the rhythm forward, and at the end of the 4’09 Tu etiam semper educis doctos per inspirationem Sapientie letificatos. spes et honor fortissimus dans premia lucis. piece, the penultimate phrase is heard in two places with a brief canonic burst. 14 Caritas abundat 6’59 Hildegard von Bingen Antiphon to the Holy Spirit No. 16. In D Dorian mode Heather Lee soprano, Kim Cunio baritone, tampurah, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Paul Jarman taragotto, Tim Constable gongs The Holy Spirit is Karitas, a female figure who came to Hildegard in repeated visionary experiences. Karitas is a divine feminine energy that can bring peace and love to all. This is an energy that is divine, fiery, omnipresent and imbued with virtue, a force that can help the mortal to soar to the heavens, beyond their bodies, into the cosmos. To support this visionary 21 experience the last two lines are sung twice. The first time, the female voice sings down the O Ierusalem aurea civitas fourth while the male voice and taragotto take the original melody in organum. The second time Hildegard von Bingen all are in octaves to glorify this great force. The Indian tampurah provides a luscious and Sequence to St Rupert, R. 474-475. In G mode providential drone to exemplify the sense of wonder. Heather Lee soprano, Mina Kanaridis soprano, Paul Jarman taragotto, Kim Cunio reed organ Caritas abundat in omnia, Karitas abounds in all beings, O Ierusalem is one of Hildegard’s master works. It is on a scale otherwise unknown in her work, de imis excellentissima most excellent, from the depths to high and has a grand textual and musical narrative. There are two main themes in the work. The first is super sidera, above the stars, Jerusalem, the city of Gold, the mythological place where all is pure, where the spiritual kingdom atque amantissima in omnia. most loving in all things. Quia summo regi osculum pacis dedit. For to the highest king she gives the kiss of peace. of God is still cherished. The second is St Rupert, the patron saint of Rupertsberg, a little-known figure apart from Hildegard’s own writings. Rupert, a blessed man, is described as an embodiment of peace, renouncing the worldly life to help others. Rupert is significant because the act of CD2 1 Dance of Ecstasy glorifying him also glorifies the women’s community at Rupertsberg. As the work builds, the boundaries between the two images blur, Jerusalem and Rupert are mentioned together, and 2’53 Rupert becomes a small part in the foundations of the physical and mystical Jerusalem. Kim Cunio Newly composed piece based on Hildegard’s modal fragments. In C Phrygian mode Kim Cunio reed organ, Llew Kiek baglama, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Paul Jarman taragotto, 2 Verses 1– IV 9’15 O Ierusalem, aurea civitas O Jerusalem, city of gold, ornata regis purpura, graced with royal purple, This newly composed piece is another great adventure. It takes individual fragments of O edificatio summe bonitatis, edifice of utmost bounty, Hildegard’s writing and weaves them with new phrases to make an instrumental realisation that que es lux numquam obscurata. your light is never darkened. could never have been played in Rupertsberg. It explores the lines of communication between Tu enim es ornata Your beauty shines East and West, and the intonation is much more Near Eastern, a sound that may well have in aurora et in calore solis. in the dawn light and the sun’s blaze. reached parts of Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries. The dance features the Turkish baglama, O beata puericia, O blessed childhood, a seven-stringed instrument with moveable frets. que rutilas in aurora, sparkling in the dawn, et o laudabilis adolescentia, And admirable time of youth, que ardes in sole – flaming in sunlight – Tunji Beier zarb 22 [23’19] 23 3 Nam tu, o nobilis Ruperte, in his sicut gemma fulsisti, unde non potes abscondi stultis hominibus: sicut nec mons valli celatur. In these, noble Rupert, you gleamed like a gem, so that you cannot be obscured by fools, just as the valley cannot hide the mountain. et quoniam in filio dei ornaris, and because you are made beautiful in cum nullam maculam habes. the Son of God, and have no blemish. Quod vas decorum tu es, o Ruperte, What a beautiful vessel you are, Rupert, qui in puericia you who in your childhood et in adolescentia tua and youth Fenestre tue, Ierusalem, cum topazio et saphiro specialter sunt decorate. In quibus dum fulges, O Ruperte, non potes abscondi tepidis moribus: sicut nec mons valli, coronatus rosis, liliis et purpura, in vera ostensione. Jerusalem, your windows are adorned wondrously with topaz and sapphire. As your brightness, Rupert, shines in them, you cannot be obscured by the moribund, just as the valley cannot hide the mountain, crowned with roses, lilies and purple in a true vision. ad deum anhelasti, in timore dei, thirsted for God, in fear of God, et in amplexione caritatis, and in the embrace of love, et in suavissimo odore bonorum operum! and in the sweetest perfume of holy works! O tener flos campi et o dulcis viriditas pomi, et o sarcina sine medulla, que non flectit pectora in crimina! O vas nobile, quod non est pollutum, nec devatorum in saltatione antique spelunce, et quod non est maceratum in vulneribus antiqui perditoris – O tender flower of the field and sweet green of the apple, O fruit with no bitter core, enticing no heart into crime! O noble vessel, that remains free from stain, not consumed in the dance in the ancient cave, not destroyed in the attacks of the ancient plunderer – Verses V–VI In te symphonizat spiritus sanctus, quia angelicis choris associaris, 24 4 3’33 The Holy Spirit makes music in you, for you belong to the chorus of angels, 5 Verses VII–VIII 4’01 O Ierusalem, fundamentum tuum O Jerusalem, your foundations positum est cum torrentibus lapidibus are set with burning stones, quod est cum publicanis et peccatoribus that is, with publicans and sinners qui perdite oves erant, who were the lost sheep sed per filium dei invente but, found by the son of God, ad te cucurrerunt rushed to you et in te positi sunt. and have found their place in you. Deinde muri tui Thus your walls fulminant vivis lapidibus flash with living stones qui per summum studium which, through the highest exercise bone voluntatis of good will, quasi nubes in celo volaverunt. soared like clouds in the heavens. Verses IX–X Et ita turres tui, O Ierusalem rutilant et candent per ruborem, 6’30 And so your towers, O Jerusalem shine red and white through the redness 25 6 et per candorem sanctorum et per omnia ornata membra Dei, que tibi non desunt, o Ierusalem. and whiteness of the saints, and through all the limbs of God made beautiful, of which you lack none, O Jerusalem. Unde vos, o ornate, et o coronati, qui habitatis in Ierusalem, et o tu, Ruperte, qui es socius eorum in hac habitatione, succurrite nobis famulantibus, et in exilio laborantibus. So all you who, adorned and crowned, reside in Jerusalem, and you, Rupert, their friend in this habitation, come to the aid of us servants who labour in exile. Who Are These? Patriarchs, Prophets and Virtues [9’55] Hildegard von Bingen Ordo Virtutum: Prologue, R. fol. 478-481. In D mode Heather Lee soprano, Cantillation chorus, Paul Jarman taragotto, Kim Cunio harmonium, conductor This major work, written in 1151, is one of the first musical dramatic works in Western history. The text has strong and emotional connotations throughout and the music is highly original, moving from the tonic to the fifth and up to the octave in most of the pieces. It was classed as an ordo (a rite) by Hildegard, which gives a clue to its performance. It is not meant to be understood in just an intellectual capacity; it is more an active ritual, where each performer and listener has the opportunity to relive the moral struggle to which Ordo Virtutum refers. The work strikingly refers to souls imprisoned in bodies, a highly developed cosmological understanding that is beyond a mere morality play. 3’32 Hildegard von Bingen Ordo Virtutum: Prologue. In D Aeolian mode Rebecca Frith voice, Kim Cunio reed organ, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Paul Jarman taragotto, Tunji Beier bells, cymbals The opening section of the Ordo Virtutum, the Play of the Virtues, is explored in great detail in this project. On this second disc it is heard as a reading [6], as a vocal piece [7-8] and as an instrumental track [10], to show how many permutations are possible with this music. Here, two completely different voices enter the stage, the Patriarchs and Prophets, and the Virtues, who set up a great contest for the soul, and indeed the whole of humanity, that is at the core of this work. A simple four-note refrain punctuates the spoken word, and soars towards the heavens. Later we hear the same text sung in the original Latin, but for now the immediacy of its meaning in English is striking. We are meant to be arrested, as we must be before a meeting with the devil, which comes later in this work. (The English text is printed next to the Latin in the next track.) 7 Prologue 5’28 Patriarchs and Prophets: Qui sunt hi, qui ut nubes? Who are these who come like the clouds? Virtues: O antiqui sancti, quid admiramini in nobis? Verbum Dei clarescit in forma hominis, et ideo fulgemus cum illo, edificantes membra sui pulcri corporis. You, holy ones of old, why do you marvel at us? The word of God grows bright in the shape of man, and thus we shine with him, building up the limbs of his beautiful body. Patriarchs and Prophets: Nos sumus radices 26 We are the roots 27 8 9 et vos rami, and you, the branches, fructus viventis oculi, the fruit of the living eye, et nos umbra in illo fuimus. and we were shadowed in him. 10 Ordo Virtutum – Instrumental Prologue 1’33 Hildegard von Bingen R. fol. 478-481. In D Aeolian mode Reprise 4’26 Kim Cunio reed organ, Llew Kiek gittern, Paul Jarman taragotto, Tunji Beier frame drum De Spiritu Sancto 4’58 We return to the start of Ordo Virtutum for the last time. The free and languid sections of ‘Patriarchs, Prophets and Virtues’ have now been set to an additive rhythm that matches the neumatic phrase Hildegard von Bingen Antiphon to the Holy Spirit, R. fol. 466. Sung in G Aeolian mode Heather Lee soprano, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Kim Cunio reed organ, Tim Constable gongs This antiphon shows Hildegard as a visionary composer. It is consistently high in the voice, and makes technical demands on the singer throughout the piece. Every main phrase starts with this lengths with changeable time signatures. It is surprising how natural this music sounds in an instrumental context, proving what a difference instrumentation and tempo make to the realisation process, as the sombreness of the original is now imbued with a transcendental quality. 11 The Soul leap of a fifth, followed by an ascending scale up to the octave. In this treatment the mysteries Hildegard von Bingen have been heightened by the use of musica ficta (feigned music) – the use of an accidental note Vision 4: 103. In A Phrygian mode 2’53 (outside the scale), to make the music more beautiful and to distance the piece from the intervals Rebecca Frith voice, Kim Cunio reed organ, Jamal Alrekabi kamanche, Paul Jarman taragotto, of darkness, including the diminished fifth, the interval of the devil. Tunji Beier bells, cymbals Spiritus sanctus vivificans vita, The Holy Spirit, life-giving life, The visions of Hildegard are startling for their clarity and lucidity, placing humanity firmly within movens omnia moving all things, the divine order, and offering great hope for the salvation of the individual, through their own et radix est in omni creatura is the root of all creation, divine spark. Some are very grounded, relating to matters on the physical plane; this vision, ac omnia de immunditia abluit, washing away all impurities, however, connects humanity through the soul to the greatest of powers. tergens crimina clearing all accusations ac ungit vulnera, and anointing wounds, et sic est fulgens ac laudabilis vita, and is thus shining life, worthy of praise, suscitans et resuscitans omnia. awakening and re-awakening all things. Et in saecula saeculorum. Amen. World without end. Amen. The soul surrounds the human body with flesh and blood to fulfil its function, just as the blowing of the wind ripens fruit on earth. We recognise God through our fiery soul and our body functions through the sacred spirit. 28 The soul is the lady of the house, 29 God has formed the human body only that the soul may live in it. quia calor solis in te sudavit because the heat of the sun sweated in you No-one can see the soul, as no-one can see God. sicut odor balsami. like a fragrance of balsam. The soul is from God, Nam in te floruit pulcher flos From you came a beautiful flower body and soul exist qui odorem dedit omnibus aromatibus which gave perfume to all the herbs as a work of God que arida erant. that were dry. everywhere, in every respect. Et illa apparuerunt omnia And these all appeared in viriditate plena. in their full greenness. Unde celi dederunt rorem super gramen Then the heavens sent down dew onto the grass et omnis terra leta facta est, and all the earth was made joyful, quoniam viscera ipsius because its womb frumentum protulerunt, brought forth grain, Et quoniam volucres celi and because the birds of heaven nidos in ipsa habuerunt. built their nests in it. is a great instrument of the divine, and Hildegard’s joyful belief in this shows in this soaring work. Deinde facta est esca hominibus, Thus food was made for man, The end of the piece, starting with Deinde facta est, expresses incredible rapture, yet is written et gaudium magnum epulantium; and great was the rejoicing of those who ate; with great tenderness. A conception of great subtlety. unde, o suavis Virgo, Hence, sweet Virgin, in te non deficit ullum gaudium. in you no joy is ever lacking. Hec omnia Eva contempsit. Eve rejected all this. Nunc autem laus sit Altissimo. But now let us give praise to the Highest. 12 O viridissima virga 10’01 Hildegard von Bingen Sequence for the Virgin, R. fol. 407. Sung in G mode Heather Lee soprano, Bronwyn Kirkpatrick shakuhachi, Kim Cunio harmonium, Tunji Beier cymbals In this piece Hildegard takes the image of the Virgin Mary, and makes it crucial to the renewal of all humanity. It is the fertility and radiating love of the Virgin that allow all of earth to function, and bring a divine link from God through humanity to the animal and vegetable kingdoms. Mary 30 O viridissima virga ave, Hail, O greenest branch, que in ventoso flabro sciscitationis born in the sweet airs sanctorum prodisti. of the saints’ prayers. Cum venit tempus Now the time is come quod tu floruisti in ramis tuis; for your branches to blossom; ave, ave fuit tibi, hail, hail to you, 31 The ensemble Heather Lee soprano Kim Cunio baritone, reed organ, harmonium, tampurah, conductor Mina Kanaridis soprano Rebecca Frith voice Cantillation choir Jamal Alrekabi kamanche Paul Jarman taragotto Bronwyn Kirkpatrick shakuhachi Llew Kiek gittern, baglama Tunji Beier daff, zarb, frame drum, tavil, cymbals, bells Timothy Constable gongs Paul Virag conductor CD1 0-@ Heather Lee is regularly in demand as a recording artist and is often heard on movie and documentary soundtracks. She performs in numerous ensembles including Oscar and Marigold, and Sefarad; her own ensemble, DIVA sings the Divine, performs at festivals around Australia. She has been involved in many broadcasts on ABC Radio National and Classic FM, and has contributed to radio and television documentaries on subjects such as mystical and early music. In 2004 Heather Lee was a peer advisor to the Australia Council for the Arts’ Music Board in vocal, choral and multicultural music. Her previous album, Sweet Dreams: Lullabies from around the world, was released on ABC Classics in 2005. Future projects include a recording of Mozart in the Czech Republic, a recording of the music of the Indian mystic Rabindranath Tagore for ABC Classics, and an ongoing investigation into sacred music from around the world, with composer Kim Cunio. Kim Cunio Kim Cunio has studied with a number of Australia’s finest musicians including Australian composer Nigel Butterley, conductor Eric Clapham, and jazz guitar legend Heather Lee Ike Isaacs. He has Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Heather Lee is a concert singer and soloist who has performed in many venues around Australia. composition, and is currently completing a Doctorate in intercultural composition. His work with the ABC has seen him compose and produce music projects for CD, radio and She has appeared with leading arts organisations and festivals including the Victoria State Opera, Queensland Symphony Orchestra and the Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane International Arts Festivals. She performs a range of styles: early music, opera and contemporary music, and is known for her improvisation and ornamentation in many styles of music. She has a Master’s degree in voice and is currently completing her Doctorate in music. 32 television. He is one of Australia’s most accomplished researching composers and was awarded an ABC Golden Manuscript Award in 2004, in recognition of his work with traditional and Islamic music. Kim Cunio has also worked as an academic, and many of his commissions have a serious research component, where he combines anthropological work with transcription. He takes the 33 position of being a participant observer in such work, and is at the forefront of an international push to preserve the dying art of Eastern Jewish (mizrachi) music. Kim Cunio plays a large number of traditional instruments, and has had a number of ancient instruments specially reconstructed. Recent commissions include The Temple Project, a realisation process setting ancient psalms and biblical texts to Baghdadian Jewish chant on replica instruments; Tomorrow’s Islam, a commission to write music reflective of contemporary, modernist Islamic thinkers; and Buddha Realms, a response to the diversity of Buddhist music, written as a response to transcriptions of Buddhist players and singers. His music has been played around the world including performances at the White House, the United Nations, and at festivals in a number of countries, and his list of commissioning organisations is significant, including the Sydney 2000 Olympics, Art Gallery of NSW, National Gallery of Victoria, Maritime Museum, Melbourne International Arts Festival, Foundation for Universal Sacred Music (USA) and many others. A number of his projects have been funded by the Australia Council for the Arts, and his touring has been funded by the Commonwealth Government. Kim Cunio is published by ABC Music Publishing. Executive Producers Robert Patterson, Lyle Chan Recording Producer Kim Cunio Recording Engineer Andrew Dixon Mastering Virginia Read Consulting Engineer Phil Snow Project Coordination Alison Johnston Editorial and Production Manager Hilary Shrubb Publications Editor Natalie Shea Booklet Design Imagecorp Pty Ltd Cover Image Photolibrary.com All Photos of Heather and Kim Avalon Studios Translations Kim Cunio and Natalie Shea Recorded in February 2006 at the Eugene Goosens Hall in the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Ultimo Centre, Sydney. Dedicated to all those who have taken the monastic vow. With thanks to Dr Constant Mews, Stephen Grant, Dr Helen De Zubicaray, Prof. Mike Atherton, Paul Virag, Pat and Sim Symons, Andrew Dixon, Virginia Read and all the players. Cantillation Sopranos Altos Tenors Basses Mina Kanaridis Anne Farrell Philip Chu Corin Bone Belinda Montgomery Judy Herskovits James Renwick Craig Everingham Jane Sheldon Natalie Shea Raff Wilson Ben Macpherson The research for this project was funded by the Australia Council for the Arts. For more information on Kim Cunio and Heather Lee: www.lotusfoot.com Contact: oscarmarigold@optusnet.com.au 2007 Australian Broadcasting Corporation © 2007 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Universal Music Group, under exclusive licence. Made in Australia. All rights of the owner of copyright reserved. Any copying, renting, lending, diffusion, public performance or broadcast of this record without the authority of the copyright owner is prohibited. 34 35