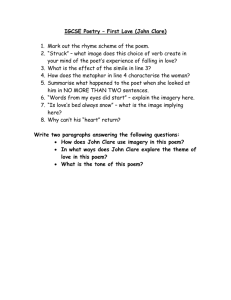

PDF version

advertisement