media law and ethics in mauritius

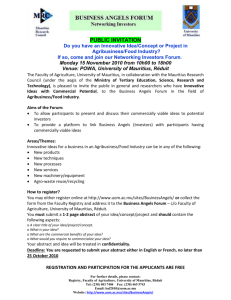

advertisement