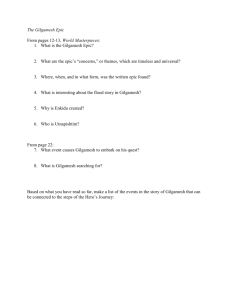

The Epic of Gilgamesh Gilgamesh, King of Uruk.

advertisement

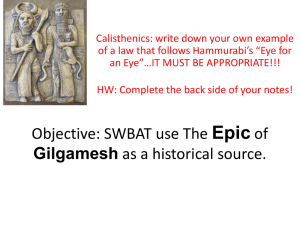

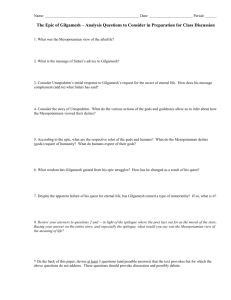

8/22/10 Dr. Theresa Thompson English 2110 Fall 2010 The Epic of Gilgamesh Gilgamesh, King of Uruk. Oldest version is written in cuneiform script, in ancient Sumerian language of Babylon, on clay tablets. Three major versions of the later Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh. Retains features of oral tradition of storytelling and employs features of written literary traditions. Articulates a specific cultural view. Old Babylonian (OB) Version, ~1700 b.c.e., author created a unified Epic about the hero Gilgamesh. Standard Babylonian (SB) elevenand twelve-tablet versions represent the two most important post-Old Babylonian Akkadian versions. There are 11 Tablets of the Epic accepted without controversy. The 12th Tablet remains controversial: Gilgamesh’s Descent into the Netherworld. Death and Irony in the Epic Abusch: “… man, hero, king, god. Gilgamesh must learn to live…. But the work emphasizes the theme of death and explores the realization that in spite of even the greatest achievements and powers, a human is nonetheless powerless against death.” “Thus in the final analysis, Gilgamesh must also come to terms with his own nature and learn to die, for he is both a man and a god, and as both he will experience loss and will die.” Vulpe: Gilgamesh's trnasforms “from a god (a being unconscious of any contradiction between his will and the world) into a man, a being greater even than his gods, a being only too conscious of the limits of his powers, but also a being able to transcend his own, immediate interests….’” “… the fundamental irony of the poem, the profound discordance between the hero's view of himself and his world, and the audience's understanding of this world, [is] the audience's foreknowledge of the hero's fate.” “This foreknowledge is crucial to the effectiveness of the poem's irony. Before Gilgamesh, we have seen the abyss. We know what he does not know, and we can thus watch him live greatness and despair as he searches for himself the solution to which we know he must come.” 1 8/22/10 Literary Language Complex tropes involve heightened language, complex mental associations. Tropes • Any language that makes a mindpicture. • Simple tropes are straightforward descriptions. • “He is the strongest in the world,…” (14) • Similetic: examination by comparison of similarities. • Analogy, contrast, allusion, parabola, allegory. • “…he is like a bull.” • Metaphoric: Tenor and vehicle. • one thing is spoken of in terms of another. The thing being spoken of is the tenor; the thing in terms of which it's being spoken is called the vehicle. Symbol / symbolism • concrete item(s) or event(s) that represent an abstract concept or range of concepts. • Example: Gilgamesh’s concrete journey represents abstract ideas about his growth, change, development, transition. Symbolism Symbolic journey: from barbarism to civilization. Gilgamesh doesn’t know how to be human: Enkidu is made to teach him. (13) Enkidu must learn to be civilized—and women make men civilized (14-15) Journey of mortal life leads to death. (26, 27-28, 32-33) Wilderness symbol: despair & fear create mental chaos— Gilgamesh seeks order, meaning. Death is the end of all flesh; Gilgamesh’s name only endures because he has been heroic in human terms. (40) Snake as symbol: Sheds his skin, symbol of eternal regeneration of nature (33, 39). Ningizzida: god of the serpent and the tree of life (40). Does this story seem familiar? Additional Elements to Consider Babylonian Captivity (586 b.c.e.-516 b.c.e.) Oral Traditions: close to the life world; adapt older stories to present situations. Gilgamesh shares many features with other ancient texts. Samson and Hercules (16, 30, 38-39) Noah and the Flood (37) Ferryman and the Ocean of Death (33-34) 2 8/22/10 Works Consulted • Tzvi Abusch, “The Development and Meaning of the Epic of Gilgamesh: An Interpretive Essay.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 121. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 2001): 614-622. • Keith Dickson. “The Jeweled Trees: Alterity in Gilgamesh.” Comparative Literature 59.3 (Summer 2007): 193-208. • Nicola Vulpe. “Irony and the Unity of the Gilgamesh Epic.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 53.4 (Oct., 1994): 275-283. • Hope Nash Wolff. “Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Heroic Life.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 89.2 (Apr. June, 1969): 392- 398. 3