AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline I. Learning Objectives—In

advertisement

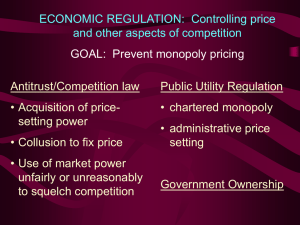

AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline I. Learning Objectives—In this chapter students should learn: A. The core elements of the major antitrust (antimonopoly) laws in the United States. B. Some of the key issues relating to the interpretation and application of antitrust laws. C. The economic principles and difficulties relating to the setting of prices (rates) charged by so‐called natural monopolies. D. The nature of “social regulation,” its benefits and costs, and its optimal level. II. Antitrust Policy, Industrial Regulation, and Social Regulation A. Antitrust policy—laws and government actions designed to prevent monopoly and promote competition. B. Industrial regulation—government regulation of firms’ prices (or “rates”) within certain industries. C. Social regulation—government regulation of the conditions under which goods are produced, the physical characteristics of goods, and the impact of the production and consumption of goods on society. III. Antitrust Laws A. The underlying purpose of antitrust policy is to prevent monopolization, promote competition, and achieve allocative efficiency. B. In the decades following the Civil War, corporations began to develop “trusts” or monopolies in industries such as petroleum, meatpacking, railroads, sugar, lead, coal, whiskey, and tobacco. C. The economic case against monopoly: 1. With pure competition, each firm maximizes profit by producing where P=MC, achieving allocative efficiency where marginal benefit = marginal cost. Monopolies maximize profit by reducing output, producing where MC=MR, but charging a higher price. This violates allocative efficiency, because society would benefit by increasing production (the benefit is greater than the cost of production). 2. The monopoly’s higher price transfers income from the consumer to the monopolist. This causes consumer resentment, because it is caused by the decision to restrict output, not by an increase in the cost of production. D. Questionable tactics were used by some of these trusts, and popular sentiment turned against them. Two mechanisms for dealing with monopolies were developed. 1. Regulatory agencies were formed to control “natural” monopolies. 2. Antitrust legislation was passed to inhibit or prevent the growth of monopolies in other industries. E. The Sherman Act (1890) is the cornerstone of antitrust legislation. 1. It contains two major provisions: a. It is illegal for contracts or combinations to restrain trade among states or with foreign nations. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline b. Those who monopolize or attempt to monopolize any part of trade among states or with foreign nations are guilty of a misdemeanor. 2. Today, the United States Department of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission, injured private parties, or state attorneys general can bring suits against alleged violators of the act. 3. Firms found violating either provision of the act could be ordered dissolved by the courts, or prohibited from engaging in the unlawful practices. Fines and imprisonment were possible, and injured parties could sue for treble damages. F. The Clayton Act (1914) strengthened the Sherman Act, which was often not explicit enough to be effective. 1. It outlaws price discrimination when it is not based on production costs and if it reduces competition. 2. It forbids exclusive or tying contracts, in which a producer forces buyers of one of its products to acquire other products from the same producer. 3. It forbids acquisition of stock in competing corporations if it lessens competition. 4. It prohibits interlocking directorates, where directors of one firm are also on the board of a competing firm, if the effect reduces competition. G. The Federal Trade Commission Act (1914) created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), an agency designed to enforce antitrust laws. 1. FTC investigates unfair competitive practices and, when appropriate, issues cease‐and‐desist orders. 2. The Wheeler‐Lea Act (1938) gives the FTC power to police “deceptive acts or practices in commerce” in order to protect the public from unfair and deceptive business practices. H. The Celler‐Kefauver Act (1950) amended Section 7 of the Clayton Act, which prohibits firms from acquiring the stock of competitors when this would reduce competition. This section had a loophole whereby firms could acquire the physical assets rather than stock of a competing company, and the Celler‐Kefauver bill closed this loophole. IV. Antitrust Policy: Issues and Impacts A. There are two distinct approaches to the application of antitrust law—one based on the structure of an industry and the other on the behavior of firms in an industry. Three landmark cases reveal the dilemma. 1. In 1911, the Supreme Court found Standard Oil guilty of monopolizing the petroleum industry through abusive and anticompetitive actions. However, it left open the question of whether every monopoly violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act. 2. The 1920 Supreme Court decision in the U.S. Steel case led to the application of the “rule of reason.” The Court decided that not every monopoly is illegal if the firm involved did not gain that power unreasonably. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline 3. In the 1945 Alcoa case, the Court held that even though a firm’s behavior might be legal (Alcoa had control over bauxite reserves, the raw material needed for aluminum), mere possession of monopoly power (90 percent of the aluminum market) violated antitrust laws. 4. These three cases point to a continuing controversy in antitrust policy: Should industries be judged by their behavior or structure? a. Structuralists claim that firms with a very large market share will behave like monopolists, and this economic performance is undesirable. b. Behavioralists argue that the relationship between structure and performance is unclear; if a firm has achieved its large market share as a result of economies of scale, should it be punished? 5. In recent years, the rule of reason has been more dominant. In 1982, the government dropped its 13‐year‐long case against IBM, deciding that IBM had not unreasonably restrained trade. More recently, the government alleged that Microsoft violated the Sherman Act, not because of its dominance in the industry, but because of its behavior. B. Defining the relevant market is important in antitrust Court decisions. 1. Courts use the 90‐60‐30 rule to determine whether a monopoly exists: 90 percent market share—definitely; 60 percent—probably; 30 percent—definitely not. 2. If the market is defined broadly, then a firm’s market share will appear to be smaller. 3. If the market is defined narrowly, then a firm’s market share may seem large. 4. In the Alcoa case, the court used a narrow definition of the relevant market—the aluminum ingot market. 5. The court defined the market broadly in the 1956 DuPont cellophane case to include all “flexible packaging materials,” such as waxed paper and aluminum foil, and therefore DuPont, which had a monopoly in cellophane, was not found to violate the law. C. Enforcement of antitrust laws varies according to the political philosophy of the presidential administration in power. 1. Aside from executive action, firms can file suit, as AMD did against Intel in 2005. 2. The overriding philosophical consideration for executive branch action is the extent to which the government should intervene in the economy. 3. The active antitrust perspective asserts that competitive forces are inadequate to insure efficiency and fairness to consumers and competing firms. Active and strict enforcement of antitrust law is favored. 4. The laissez‐faire perspective holds that the market will correct for any abuses of monopoly power by creating profit incentives that attract new and stronger competitors. Through the process of creative destruction, new products and processes will replace those held by current monopolies. There is no reason to AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline enforce antitrust policy, as the long‐run competitive process will effectively undermine monopolies. D. The effectiveness of antitrust laws is difficult to judge. The government has generally been lenient in applying antitrust laws to firms that have grown “naturally.” 1. Antitrust laws have generally not been applied unless a firm has very high market share and there is evidence the firm used abusive conduct to achieve or maintain its market dominance. In 1982, AT&T was charged with violating the Sherman Act by engaging in several anticompetitive actions to keep its monopoly in telephone communications. In an out‐of‐court settlement, AT&T agreed to divest itself of its 22 regional phone‐operating companies, but was allowed to keep its long‐distance service operations. 2. In 2000, a federal district court found Microsoft guilty of violating the Sherman Act. The court’s remedy was to split Microsoft into two companies and to prohibit each from in engaging in anticompetitive behavior. Microsoft appealed the decision to a higher court, and in 2002, the Court of Appeals upheld the finding of abusive monopoly but imposed behavioral restrictions, rather than splitting the company. 3. Mergers are treated differently, depending on the type of merger and the effect on competition. a. Horizontal mergers are between companies selling similar products in the same market (Chase Manhattan and Chemical Bank, Boeing and McDonnell Douglas, Exxon and Mobil). b. Vertical mergers are between firms at different stages of the production process in the same industry (PepsiCo’s merger with Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and Kentucky Fried Chicken, which it supplied with beverages; PepsiCo spun off the restaurants in 1997). AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline c. Conglomerate mergers are between firms in unrelated industries (Walt Disney Company and American Broadcasting Company, and America Online and Time Warner). 4. The Herfindahl index is used as a guideline by the federal government to decide whether the merger will be allowed. a. Recall from Chapter 11 that this index is the sum of the squared market shares of the firms in the industry; 10,000 would be the index for a pure monopoly (100 squared). b. Generally, the post‐merger index must be above 1800 and significantly changed by the merger for the government to challenge a horizontal merger. c. Other factors, such as economies of scale, the degree of foreign competition, the ease of entry of new firms, and whether one of the merging firms is under major financial stress, are also considered. Horizontal mergers between Staples and Office Depot, WorldCom and Sprint, and Hughes (DirecTV) and Echostar (DISH Network) have been blocked. 5. Vertical mergers are usually ignored unless they are between two firms who are each in highly concentrated industries. A proposed merger between Barnes & Noble and Ingram Book Company was abandoned when it appeared that the FTC was going to take action; the merger would have enabled Barnes & Noble to set the wholesale price of books charged to their retail competitors such as Borders and Amazon. 6. Conglomerate mergers have generally been permitted. 7. Price fixing is treated strictly. Evidence of price fixing—or even a conspiracy to fix prices—can elicit antitrust action. Such violations are called per se violations because they are illegal in and of themselves; they are not subject to the rule of reason. 8. CONSIDER THIS … Of Catfish and Art a. ConAgra and Hormel paid $21 million to settle their roles in nationwide price‐ fixing of catfish. b. Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) paid $430 million to resolve the government’s antitrust action after admitting to fixing the prices of citric acid, an additive to livestock feed, and high‐fructose corn syrup. c. UCAR International was fined $110 million for scheming with competitors to fix prices and divide up the graphite electrode market. d. The auction houses at Sotheby’s and Christy’s conspired over a 6‐year period to fix commission rates. e. Samsung, Hynix Semiconductor, Infineon, and Micron were fined $645 million for fixing prices of dynamic random access memory chips (DRAMs). f. British Airlines and Korean Air were fined $300 million each for conspiring to fix fuel surcharges on passenger tickets and cargo. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline g. Five manufacturers of liquid crystal displays (LCDs) were fined more than $860 million for fixing the prices of displays they sold to Dell for computers. h. Three international cargo airlines were fined $214 million for conspiring to fix international airline cargo rates. 9. The government generally permits price discrimination because it rarely reduces competition. 10. The federal government also has strictly enforced the Clayton Act’s prohibition of tying contracts. The government has stopped movie distributors from forcing theaters to buy the projection rights to a full package of films as a condition of showing a blockbuster movie. Tying contracts, such as Microsoft “bundling” its Internet Explorer browser with its Windows operating software, were declared illegal. E. Has antitrust policy been effective in achieving its goal of promoting competition and efficiency? 1. Antitrust policy has not been effective in restricting the rise or breaking up monopolies or oligopolies resulting from internal expansion. 2. Antitrust laws have been more effective against predatory or abusive monopoly power, but the effectiveness has been slowed because of the long legal process. 4. Antitrust policy has been effective in blocking anticompetitive mergers and prosecuting price fixing and tying contracts. F. Most economists conclude that antitrust policy has been moderately effective in promoting competition and efficiency. Others, though, believe that with the era of rapidly changing technology, American antitrust policy is anachronistic. V. Industrial Regulation A. Natural Monopoly 1. A natural monopoly exists when economies of scale are so extensive that a single firm can supply the entire market at lower average total cost than could a number of competing firms. Examples include public utilities, such as electricity, water, and natural gas. In such cases, it is more efficient to have only one producer. 2. Two possible alternatives exist for protecting society in such cases. a. Public ownership is one solution, as occurs with the Postal Service, local water systems, and many local mass transit systems. b. Public regulation (industrial regulation) has been the option utilized most extensively in the United States. Regulatory commissions regulate the rates charged by monopolies. 3. The rationale (public interest theory) for public ownership or industrial regulation is that uncontrolled monopoly power can be abused. The goal of industrial regulation is to allow the public to benefit from the lower costs of a natural AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline monopoly, while avoiding the reduction in output associated with an unregulated monopoly. 4. Regulators seek to establish rates that will cover production costs and yield a fair return of normal profit to the enterprise (P = ATC). B. Problems with Industrial Regulation 1. An unregulated firm has the profit incentive to reduce its production costs. If a regulated firm lowers its operating costs, the increase in profits will lead the commission to lower its rates, so as to reduce profit. 2. Higher production costs are passed on to the consumers in the form of higher rates. A regulated firm might give higher salaries to its workers without an increase in marginal productivity. 3. Although a natural monopoly reduces costs through economies of scale, industrial regulation fosters considerable X‐inefficiency. 4. Industrial regulation can lead to continuing monopoly power after the conditions of natural monopoly are gone. a. Technological changes create potential competition for the regulated industry (trucks compete with trains; cell phones compete with landline phones). b. Regulators, by blocking entry or extending regulation to competitors, may perpetuate a monopoly where a natural monopoly would erode. The beneficiaries of outdated regulation are the regulated firms and their employees; the losers are customers and potential entrants. C. Legal Cartel Theory 1. Proponents of this theory contend that regulators guarantee a return to the regulated firms while blocking entry and dividing up the market—activities that would be illegal in unregulated markets. 3. Occupational licensing is an example of this theory in certain labor markets. VI. Deregulation A. Deregulation came about in the 1970s and 1980s as a result of the greater acceptance of the legal cartel theory, increasing evidence of inefficiency in regulated industries, and the contention that government was regulating potentially competitive industries. B. Airline, trucking, banking, railroad, natural gas, television broadcasting, electricity, and telecommunications industries have been largely deregulated. C. Although some criticize deregulation, on balance it appears to have benefited consumers and the economy. 1. Benefits to society through lower prices, lower costs, and increased output have come primarily from airlines, railroads, and trucking. 2. Deregulation has led to technological advances in new and improved products. D. Deregulation in the electricity industry has generated significant controversy. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline 1. The industry is most deregulated at the wholesale level, allowing wholesalers to build facilities and sell electricity to distributors at unregulated prices. 2. Some states have also deregulated retail electricity prices and, for the most part, electricity rates have fallen for consumers. 3. In California, where wholesalers were deregulated and retailers regulated, a dramatic increase in wholesale prices in 2001 resulted in substantial financial losses for retail providers, as they were legally prevented from raising retail prices to cover the higher costs. The problem was exacerbated by the fraudulent activities of energy‐trader Enron. VII. Social Regulation A. Social regulation differs from industrial regulation in that it is concerned with the conditions under which production occurs, the impact of production on society, and the physical qualities of the goods produced. Table 18.2 lists the main federal regulatory commissions engaged in social regulation. B. Distinguishing Features 1. Social regulation applies to many or all industries and affects many people. 2. Social regulation involves government in the details of production. Regulation often dictates the design of products, the conditions of employment, and the nature of the production process. 3. Social regulation has expanded rapidly in last two decades. As society has become more affluent, it has focused more attention on product quality, pollution, working conditions, and equality of economic opportunity. C. The Optimal Level of Social Regulation 1. While most economists agree on the need for social regulation, there is disagreement on the optimal level of regulation. 2. In Support of Social Regulation AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline a. Although the cost of social regulation is high, the appropriate test is to determine whether the benefit exceeds the cost (safer workplaces, less pollution, safer products, and reduced discrimination). b. The benefits are difficult to measure and are often realized only after time has passed, so society tends to underestimate the benefits of a policy. c. There are continuing problems that can best be addressed through additional social regulation (greater regulation of certain food products, health care services, and insurance). 3. Criticisms of Social Regulation a. Many standards cause marginal costs to exceed marginal benefits, leading to overregulation. b. Many regulations are poorly written, resulting in regulation beyond the original intent. c. Decisions are sometimes made on the basis of inadequate information. d. Many rules have unintended side‐effects, such as lighter, fuel‐efficient cars having higher fatality rates. e. Overzealous workers who believe too much in regulation work for these agencies. D. Two Reminders 1. There are costs to social regulation; it can produce higher prices, stifle competition, and reduce competition. 2. Social regulation can increase economic efficiency and society’s well‐being by improving working conditions, removing unsafe products, and reducing pollution. VIII. LAST WORD: United States v. Microsoft A. In May 1998, the federal Justice Department, 19 states, and the District of Columbia filed charges against Microsoft under the Section 2 of Sherman Antitrust Act, arguing Microsoft had taken a series of actions designed to maintain its “Windows” monopoly. B. Microsoft denied the charges, arguing that it had achieved success through product innovation and lawful business practices. It also pointed out that monopoly was transitory because of rapid technological advances. C. In June 2000, the district court ruled Microsoft a monopoly, with 95 percent of the market share for software to operate Intel‐compatible personal computers. D. Although being a monopoly is not illegal, the court stated that Microsoft had violated the Sherman Act by using anticompetitive means to maintain and broaden its monopoly power. The court ruled that by tying Internet Explorer to Windows and providing the browser at no charge, Microsoft acted illegally in competing against Netscape’s Navigator and Sun’s Java programming language. AP Microeconomics – Chapter 18 Outline E. The court ordered Microsoft to be split into two companies which were prohibited from entering into joint ventures with one another. F. In 2001, the Court of Appeals ruled that Microsoft had illegally maintained its monopoly, but reversed the decision to break up Microsoft. The final settlement required billions of dollars in fines and compensation to competitors and enacted several behavioral remedies. 1. Microsoft is prevented from retaliating against any firm that competes with Microsoft by developing, selling, or using software that competes with Microsoft Windows or Internet Explorer. 2. Microsoft is required to establish uniform royalties and licensing terms for any computer manufacturer wanting to include Windows on its personal computers. 3. Microsoft must allow manufacturers to remove Microsoft icons and replace them with others on the Windows desktop. 4. Microsoft must provide technical information so that other companies can develop software that is compatible with Windows and other Microsoft products.