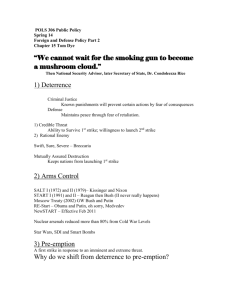

Bridging Deterrence and Compellence - MARIA SPERANDEI

advertisement