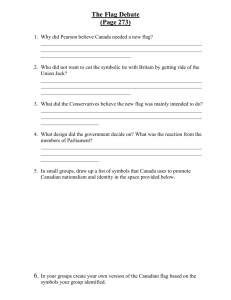

Texas v. Johnson tutorial

advertisement