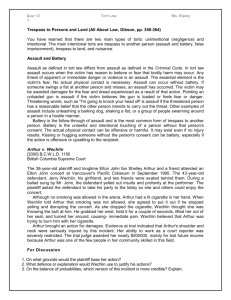

fair trespass - Columbia Law Review

advertisement