The Professional Athlete's Right of Publicity

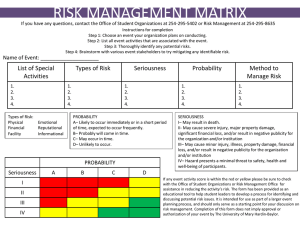

advertisement