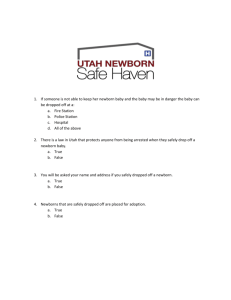

The Healthy Newborn

advertisement