Changing Over Time, Over Time: A Behavioural Self

advertisement

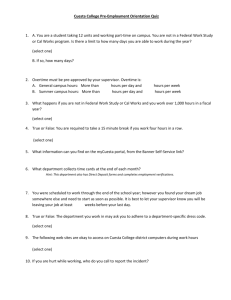

Reducing Overtime, Over Time By Kelli Buckreus Abstract Behavioural self-control was utilized to reduce overtime work by one full-time salaried worker exhibiting characteristics of work addiction that fit poorly with existing workaholic type classifications. Underlying psychosocial dynamics relating to prior experience of economic adversity were explored. An intervention comprised self-talk/self-instruction and modification of environment as independent variables. A 71% reduction in overtime hours was observed over a five-week intervention period, and was maintained once independent variables were withdrawn. Conclusions drawn include the need for a new workaholic type classification that accounts for the role of voluntariness and organizational culture in workaholism characterized by high work initiation and completion. Keywords: work addiction, workaholism, overtime, overwork, behavioural self-control, work-home interference Introduction As globalization rapidly moves us towards a “24-hour society”, technology – workconnecting technology, in particular – is playing a role in redefining organizational and work cultures (Gupta, 2005; Kreitzman, 1999; Stoner, Stephens, & McGowan, et al., 2009). Although greater connectivity enables more flexibility in terms of work times and locations, it poses greater risk for overtime work intruding into non-work life, leading to work-home interference and conflict (Albertsen, Rafnsdóttir, Grimsmo, Tómasson, & Kauppinen, 2008; Jansen, Kant, Kristensen, & Nijhuis, 2003; Jansen, Kant, Nijhuis, Swaen, & Kristensen, 2004; Porter, 2004; Schneider & Waite, 2005; Skinner & Pocock, 2008; Stoner et al., 2009). Workers (salaried workers, in particular) may experience new pressures for engaging in work outside of normal work hours, mediated by workconnecting technology (Cherry, 2004; Gupta, 2005; Stoner et al., 2009). Stoner et al (2009) describe a work culture shift wherein connectivity may foster greater competitiveness and expectations for overtime, and thereby reducing work flexibility. Overwork (overtime, excessive work) is work above and beyond that required by the job, often becoming the individual’s dominant life activity (Schaufeli, Taris, & Bakker, 2006; Scott, Moore, & Miceli, 1997). While overwork may correlate to positive work motivation, work engagement, positive mood and personal investment in human capital (e.g., reputation and skills development that may lead to higher future income) (Beckers et al., 2007; Cherry, 2004; Haber & Goldfarb, 1995; Schaufeli et al., 2006; Van Wijhe, Schaufeli, & Peeters, 2010), for some, overwork represents an addiction – workaholism – with characteristics similar to alcoholism (Porter, 1996; Schaufeli et al., 2006). Neglect of family/personal relationships and responsibilities; anxiety if away from work; non-delegation of tasks; and striving for better feelings of self are among the characteristics defining work addiction (Porter, 1996; Schaufeli et al., 2006). Schaufeli et al. (2006) distinguish “bad workaholism” from “good workaholism”1, but describe excessive work as a component of both. Bad workaholism comprises compulsion as a discrete component, in addition to excessive work, and it is compulsion that defines the addiction (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Compulsive work, not excessive work, was found to be associated with perceived and actual ill health and poorer wellbeing (Schaufeli et al., 2006). However, Schaufeli et al., (2006) do not explore psychological factors that may underlie work addiction. An interesting study by Rowlands and Handy (2012) considered the addictive characteristics of the project-based work / employment environment in the New Zealand film industry. Qualitative data gathered through interviews with film industry workers revealed that unpredictable employment and the cycle between periods of highly rewarding work and periods of unemployment create psychosocial dynamics that are characteristic of addiction amongst these workers (Rowlands & Handy, 2012). One principle of operant theory that Watson and Tharp (2007) describe is that “[i]ntermittent reinforcement increases resistance to extinction” of a behavior, meaning that behavior that is randomly reinforced persists longer, compared to behavior that is continuously reinforced, when reinforcement is withdrawn (Watson & Tharp, 2007, p. 120-121). Experiencing unpredictability in employment and economic status may function as intermittent reinforcers that could contribute to maladaptive behavior such as work addiction. Behavioural self-control strategies have been shown to be effective for addressing addiction in smoking, drinking and drug use (Walters, 2000; Watson & Tharp, 2007). Since characteristics of work addiction are similar to those of alcoholism (Porter, 1996; Schaufeli et al., 2006), behavioural self-control may be an appropriate approach for addressing work addiction. Behavioural self-control has been utilized effectively to treat other non-substance related addictions, such as compulsive 1 Work engagement, characterized by vigor, enjoyment, and absorption in work, but lacking the compulsive drive. (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001; Schaufeli et al., 2006). shopping and gambling (Breen, Kruedelbach & Walker, 2001; McConaghy, Blaszczynski, & Frankova, 1991; Mueller et al., 2008; Van Wijhe et al., 2010). However, research specific to the treatment of workaholism, utilizing behavioural self-control in particular, is lacking (Van Wijhe et al., 2010). Rationale For quite some time I have been unhappy in my current job in (academic) health research. I invest substantial amounts of overtime, receiving no direct compensation or time off in lieu. Workhome interference is prevalent, as my overtime work has become ubiquitous during my off-work hours. This burden of overtime has meant postponing completion of my graduate studies, less time to spend with my family, and resulted in a period of physician-prescribed sick leave in 2012. Maintaining boundaries between the work and non-work areas of my life seems impossible at times, beyond my control, suggesting addictive characteristics to my overwork behaviour (compulsion, in particular). A prior experience of homeless linked to income insecurity may underlie psychosocial dynamics akin to those described by Rowlands and Handy (2012), and may have influenced my development of a work addiction. This paper reports on a self-management project that aimed to reduce the daily and weekly unpaid overtime I typically work. An intervention comprised the implementation of two independent variables: (a) self-instruction combined with self-talk that incorporated disputation and rationale restructuring, and (b) modification of environment that incorporated stimulus narrowing (location and time restrictions for overtime work) and environmental stimulus control. A structured journal supplemented quantitative data collection, identifying antecedents and consequences surrounding the target behavior, which informed the development of content for the self-talk variable. A daily activity log provided insights on the circumstances in which I was most likely to engage in overtime, and helped determine optimal timing and location for stimulus narrowing. Robinson (1998) proposed four types of workaholic: (a) bulimic workaholics, perfectionists with all-or-nothing approaches who have difficulty starting projects then work to exhaustion to finish them; (b) relentless workaholics who take on an excessive workload that impedes their time for doing careful work; (c) attention-deficit workaholics, characterized by high work initiation but low work completion; and, (d) savouring workaholics, characterized by low work initiation and completion. While I tend towards aspects of (a), (b) and (c), none of these categories sufficiently describes my situation. Novel Research The present project advances Schaufeli et al. (2006) and Rowlands and Handy (2012) by having explored aspects of work addiction in a worker in a fulltime continuing (>10 years) salaried position, and the relationship between compulsive work and prior experience of unpredictable economic status. Of particular interest were the psychosocial effects of pressure and relief from economic adversity, and their long-term implications for work behaviour and work addiction. As an added dimension, this project explored the role of work-connecting technology as an enabler of work addiction. This study also includes an intervention. This paper describes a case that fits poorly with the four workaholic types proposed by Robinson (1998), and proposes that a new/fifth workaholic type might be added. My self-talk independent variable integrated the technique of disputation (Seligman, 1998) with rational restructuring (Watson & Tharp, 2007) in applying the overall self-modification plan framework described by Watson and Tharp (2007). Method Overview The project was implemented over a 14-week period from January 27th to May 4th, 2014. The project generally followed the self-modification plan framework described in Watson and Tharp (2007), incorporating strategies that are also described in Kafner and Gaelick-Buys (1991). After identifying the target behaviour I wished to address – overtime work – I wrote and signed a basic self-contract committing myself to this self-modification project. My major goal was to reduce the amount of daily and weekly overtime I worked, with the subgoals of eliminating overtime worked outside my home and limiting overtime worked at home to a maximum of 30 minutes per day (maximum 3 ½ hours per week). I embarked on action-oriented tasks that included self-monitoring, environment modification, self-instruction, disputation / rational restructuring, and self-reward (Kafner & Gaelick-Buys, 1991; Watson & Tharp, 2007). A four-week baseline period was followed by an eight-week intervention period, and then a final two-week period during which the intervention was withdrawn to evaluate whether behavioural change had been achieved. The Participant I am a 43-year-old female living in a small town north of Edmonton, Alberta. I live with my husband and six-year-old daughter in a home that we own. My daughter attends grade one, and outof-school care to accommodate her parents’ work schedules. My husband is a Government of Alberta executive. Since 2004 I have worked in a full-time salaried position in health research at the University of Alberta. I do not receive pay for overtime hours. My daily commute time to-and -from work is typically 90 to 120 minutes. I am nearing the completion of a Master’s degree in educational studies, which I hope will support a career change. My graduate GPA is 4.0. My husband’s income falls within the top ~5% of Canadian incomes, and mine falls within the top ~10% (per Canada Census data for the 2009 tax year) (Alini, 2011). I took a 12-month maternity leave when my daughter was born in 2007, and had intended to reduce my work hours to part-time once I returned from leave. Upon returning to work, however, my responsibilities and hours (including overtime) increased due to a manager retiring. Currently, I am not able to spend as much time with my daughter as I would like, which is emotionally distressing for me. When I am not working overtime, I frequently feel the need to be alone, which is consistent with research that shows a correlation between overtime work and increased need for recovery / downtime / time alone (Jansen et al., 2003; Jansen et al., 2004). I manage a number of research projects and frequent travel out of town is required. I am oncall during my off-work hours to deal with emergencies and urgent matters that may arise for my research field team while they are travelling. These communications generally utilize email or textmessaging accessed via my iPhone, and are infrequent. The bulk of my overtime is undertaken in response to email contact with my supervisor, who works a differential schedule (evenings and weekends). My supervisor makes tasks requests during my off-work hours, and I feel pressure to comply, sometimes working past midnight on weeknights. Since I began this job, there has been consistent tacit communication that working overtime is expected. At times when I have refused overtime, I have lost skill development opportunities and publishing opportunities to colleagues. I previously worked as Director of Communications for an international law firm in Toronto, Ontario. Working overtime was part of the firm’s culture, and I typically worked 60-80 overtime hours each month, and I was paid for this overtime. I have been working since that age of 15, often in supervisory and leadership roles. Lowpaying part-time work funded me through my undergraduate studies, during which time I experienced a brief period of homelessness (in downtown Toronto). I grew up in the Edmonton area with my mother, who was a homemaker, my father, who worked full-time in provincial government, and my younger sister. My family struggled financially, and my mother worked very hard to maintain an appearance of social affluence, which included not allowing my sister or me to speak in certain social settings (e.g., gatherings of extended family). My mother discouraged independence in her children, was very controlling, and utilized humiliation to keep my sister and me in line. For instance, in my early teens I became concerned about nutrition (we did not have particularly good nutrition at home), and when I tried to talk about it with my mother, she laughed at me and told me I would still get fat if I ate too many apples. I had an eating disorder during my mid- and late teen years, which resolved without treatment shortly after leaving home. I left home for the first time when I was 20-years-old to attend university in Toronto. My mother’s last words to me before I boarded the plane to go were “you’ll never make it on your own”. My later experience of homelessness, therefore, functioned for me as the realization of my mother’s prediction. I have never admitted the fact of my homelessness to my parents or sister. I am in fair health, except for being obese, though I have none of the conditions that commonly accompany obesity (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol). While undertaking this project I was simultaneously enrolled in a managed weight loss program that incorporated behavioural self-control strategies for which I engaged in data collection and independent variables similar to those I will describe for this project. Data Collection Overtime2 was defined as any time spent working after 4:00 pm on weekdays, and anytime on weekends and during vacation days and sick days. Duration (in minutes) of each incidence of overtime, as well as the location each incidence took place (whether outside or inside my home), were recorded as quantitative data. Antecedents – thoughts, feelings, environmental cues – and consequences surrounding each incidence of the target behaviour were recorded in a structured journal as qualitative data (Watson & Tharp, 2007). Quantitative data was recorded as an entry in the proprietary “Notes app” on my iPhone, and initially (through the baseline period) comprised a log of daily activities that included the start- and end-time of each activity. Activities logged included such things as driving to work weekday mornings, work time, taking my daughter to her dancing class, overtime work, working with my 2 Overtime is unpaid daughter on her reading homework, watching television with my husband, and doing course work. At the end of each week this data was transferred to a spreadsheet. Overtime data was copied and tabulated separately, and minutes were converted to hours for calculating weekly means. Daily (in minutes) and weekly (in hours) overtime were plotted on separate line graphs depicting total overtime and overtime by location (outside or inside my home). After the baseline period, only overtime minutes continued to be recorded for quantitative data. Qualitative data was similarly recorded in my iPhone, and was transferred to a spreadsheet at the end of each week. Through the baseline period, qualitative data was collected and analysed simultaneously as part of a reflective process that included identifying early links in the chain of antecedents leading to the target behaviour (Kafner & Gaelick-Buys, 1998; Watson & Tharp, 2007). Key words and concepts were identified then grouped together, and a descriptive sub-theme representing each group was identified. An overarching theme was then identified. New data was added as it was collected, with groups and themes added and/or refined as this reflective process unfolded. Statements developed through disputation and rational restructuring were added in response to antecedent thoughts and emotions (Seligman, 1998; Watson & Tharp, 2007). Baseline data was recorded over a four-week period. My work demands fluctuate throughout the month relative to my staff’s travel patterns (e.g., two-to-three weeks per month, but not the same weeks each month), and my administrative tasks (e.g., financial reconciliations, payroll) also occur at different times throughout the month. Recording baseline data over four weeks captured these fluctuations, allowing for the calculation of a weekly mean to characterize a typical pattern of weekly overtime. Independent Variables An eight-week intervention period starting in Week 5 of data collection comprised two independent variables: (a) combined self-talk / self-instruction that incorporated disputation and rational restructuring; and, (b) modification of environment that incorporated stimulus narrowing and environmental stimulus control, implemented in two phases. Stimulus narrowing included the imposition of specified times during and a 30-minute limit for overtime work through Phase II. Self-instruction. Self-instruction consisted of directions given to myself at the start and finish of my allotted 30-minutes of overtime, and directing myself not to engage in overtime when the urge arose outside of the allowed times. Self-instructions were sometimes spoken verbally and sometimes recited in my mind. Common self-instructions included: “It’s time to start/finish overtime”; “This isn’t the right time for overtime, do something else”; “You’ve already worked a full day, you’re don’t have to do anymore work today”; “Work is done, do something else”; and simply “No”. Self-instruction was also utilized to redirect my attention to competing activities, such as game apps or talking to someone (Watson & Tharp, 2007). Self-talk. Self-talk was utilized in conjunction with self-instructions, as well as anytime I experienced anxiety over not engaging in overtime, and consisted of substituting positive statements for negative ones (Watson & Tharp, 2007). The content of my self-talk emerged from analysis of my structured journal, primarily the antecedent thoughts and feelings recorded. Seligman (1998) describes the effectiveness of disputation in redefining beliefs through a process that considers evidence, alternatives, implications and usefulness of the beliefs. Although I did not follow Seligman’s (1998) full framework3, I incorporated aspects of the disputation process in analyzing my structured journal, and the disputations generated served as the content of my self-talk (see Table 1). The process of disputation is similar to rational restructuring described by Watson and Tharp (2007), through which self-talk is refocused on cool thoughts, rather than hot thoughts (which elicit a stress response), and the 3 I did not utilize the categories Seligman proposes for the disputation record: Adversity (A), Belief (B), Consequence (C), Disputation (D), Energization (E) (Seligman, 1998) cool antecedents become behavioural cue. My self-talk disputations, therefore, functioned as cool antecedents to calm anxiety I experienced over not engaging in overtime. The data recorded in my structured journal during the baseline period helped me identify an overarching antecedent theme – fear of losing independence – cuing my target beahviour. This theme links back to my prior experience with homelessness, and even further back to my struggle in gaining independence from my mother, early events that may have led to the psychosocial dynamics that underlie my work addiction. Therefore, in developing my disputations/rational restructuring, I was careful to include content that would support feelings of independence. I avoided self-talk statements that might directly undermined feelings of independence, such as “My husband earns enough money to take care of everything”. Two consequent thoughts/feelings were consistently recorded in my structured journal: (a) anger (directed towards my job, not myself) that the time I spent working overtime could have been spent with my daughter instead; and, (b) anger (directed towards my job, not myself) that the time I spent working overtime could have been spent on my course work instead. These similarly reflected the theme of independence loss. Therefore, additional self-talk content included statements reminding myself that I have the capacity to choose how I use my time; my daughter is more important to me than my job; spending time with my daughter is more important to me than working overtime; and completing my graduate studies may lead to a different/better job. Two consequent thoughts/feelings were consistently recorded in my structured journal: (a) anger (directed towards my job, not myself) that the time I spent working overtime could have been spent with my daughter instead; and, (b) anger (directed towards my job, not myself) that the time I spent working overtime could have been spent on my course work instead. These similarly reflected the theme of independence loss. Therefore, additional self-talk content included statements reminding myself that I have the capacity to choose how I use my time; my daughter is more important to me than my job; spending time with my daughter is more important to me than working overtime; and completing my graduate studies may lead to a different/better job. Table 1 Structured Journal Excerpts: Antecedents Examples, Sub-themes and Self-talk Content Antecedent Thoughts/Feelings I should / have to work overtime or… • I will lose my job and my income. • I will lose my home and everything, and not be able to prevent it from happening. • I will not “make it” on my own. Sub-themes Overarching Theme • Even if I lose my job, I will not be homeless again the next day. • I’m eligible for 5 months layoff notice. This would give me lots of time to find a new job. • I’m protected by a union. I can’t just get fired without first getting support to help me improve my job performance over a period of time. I would get a chance to turn things around. • I have made it on my own. I put myself through university, have had good jobs, and have built a life for my family. Fear of economic adversity I’m scared… • Of losing everything. • That I won’t be able to take care of myself, my family. I should / have to work overtime or… • I know my boss is working right now, and I know she will have something she wants me to do. If I don’t, she will think I am a slacker. • I will get behind in my work and will not be able to catch up, and will be passed over for other more interesting tasks. • I will lose opportunities (for experience, skills development, etc.) to my colleagues. • I will miss out on future opportunities and higher income because of the opportunities I am being passed over for now. I feel… • Like I can’t catch up, I can’t compete. • That people will judge be badly. • Like I’m wasting my life, and I’m running out of time. Fear of losing independence Fear of failing Self-Talk Statements (disputations, cool antecedents) • I’m not a slacker. I work really hard and I do good quality work. I rarely get behind in my work, and if I do I can delegate to others or ask for help. I don’t have to do it all alone. • My boss tells me all the time that I am integral to all she does. She needs me and values me. • I’ve had the chance to development management skills, which my colleagues haven’t. These skills are transferrable to other fields, and qualify me for higher paying jobs. • I have always had excellent performance reviews. My overtime work is always acknowledged. • More tasks/opportunities now would mean taking on even more work. • I want a career change, anyway. I’m creating my own opportunities. Modification of Environment Baseline data confirmed that I engaged in overtime work within two domains: inside and outside my home. Therefore, addressing the target behaviour in relation to each of these domains became sub-goals of this project, defining Phase I and Phase II, respectively. Information recorded in my structured journal and in my daily activity log indicated that environmental antecedents for the target behaviour included natural breaks between family/personal responsibilities/activities (ex. after dinner, before doing dishes); times when competing family/personal responsibilities are things that do not have to be done (ex. I can put off doing the readings for my course for another night, I can skip reading my daughter a bedtime story tonight); when I am alone and not directly engaged in an activity (when I am waiting for my daughter during her dance class); checking my work e-mail; and, sound alerts indicating incoming text messages. The consequences recorded in my structured journal consistently reflected an association between engagement in overtime work and feelings of deficit in time spent with my daughter and on my graduate course work, as described above. Modification of environment was implemented as an independent variable in two successive phases, each phase targeting a location-based sub-goal primarily through stimulus narrowing and supported by environmental stimulus control. Kafner and Gaelick-Buys (1991) describe stimulus narrowing as “strengthening the association between a behaviour and a specific setting; that is, the behavior is put under Sd control” (Kafner & Gaelick-Buys, 1991, p. 337), while environmental stimulus control involves altering “physical and social environments to prevent a response” (Kafner & Gaelick-Buys, 1991, p. 336). Phase I aimed to eliminate overtime worked outside my home, in order to strengthen the association between the target behaviour and my home. I simply refrained from working overtime when I was not at home. Self-instruction and self-talk were utilized to support these efforts. Environmental stimulus control included closing the email application on my iPhone so that I would have to login to access it, which created a barrier to engaging in the target behaviour. Additionally, to deal with high-risk situations for the target behaviour, I provided myself with alternative activities, such as game applications and e-books on my iPhone, course textbooks, and social interaction with other people, which facilitated incompatible behaviour (Watson & Tharp, 2007). During Phase I, I continued to work overtime unrestricted while at home. Once the Phase I sub-goal was achieved, Phase II was implemented to reduce the amount of overtime worked at home through an imposed time limit – 30 minutes maximum per day – and restricting the location of overtime work to the chair in the “cat’s corner”4 of our home library. This was done to strengthen the association between overtime and a specific location in my home, so that this chair would become an antecedent, while cues elsewhere in my home would weaken (Kafner & Gaelick-Buys, 1991; Watson & Tharp, 2007). I chose an unpleasant location in my home in an attempt to increase response costs and render overtime as a physically unpleasant activity, as a deterrent (Kafner & Gaelick-Buys, 1991). Overtime work was the only activity I engaged in while sitting in that chair. Environmental stimulus control during Phase II included timing my overtime with my iPhone clock, with an alarm sounding when my 30 minutes were up, and sandwiching my overtime between activities that comprised incompatible behaviours5 (e.g., between finishing dinner and putting my daughter to bed) (Watson & Tharp, 2007). This alarm became a cue for me to end my overtime and to move on to my next activity. To help stay within my 30 minute limit, I only responded to emails and undertook tasks that were truly urgent (e.g., matters that might have 4 Our house has four floors, and we have one elderly cat who has difficulty climbing stairs. She has always preferred the second floor, which houses our library and our bar/lounge. We keep food and water for her in the drawing room, and keep her litter box in a corner of the library, so that she does not have to climb stairs. 5 Information in my structured journal indicated feeling rushed in carrying out family/personal responsibilities, such as making lunches for the following d ay, doing laundry, doing course work, and working with my daughter on her reading homework. Therefore I increased my participation in these activities as incompatible behaviours, especially during high risk times for the target behaviour. Increased free time resulting from my overtime limit represented high risk times. prevented my field team from continuing their work the following day). I worked on any non-urgent tasks until my 30-minute time limit, then I set a time the following day/week to continue working on the task. For non-urgent tasks requested by my supervisor, I sent an email indicating when I planned to work on and complete the task, which represented a positive/active response6. Environmental stimulus control also included advising my staff to only contact me by textmessaging, and only for emergencies and truly urgent matters. I assigned a specific alert tone to my staff7 to provide me with an audible cue that I was required to attend and respond to the communication. Self-instruction and self-talk provided support throughout Phase II. Reinforcement Relief from anxiety was a consequence I recorded in my structured journal, appearing to function as a reinforcer for the target behaviour. This reinforcer could be rearranged/redefined through the use of proxies that facilitated relaxation and anxiety release (Watson & Tharp, 2007). I chose spa days as self-rewards for meeting my Phase I and Phase II sub-goals. As a more immediate positive reinforcer, I chose sitting quietly in my bedroom with the lights out while petting my cat8 for 15 minutes when I was successful in meeting my daily target9. For instance, during Phase I, I would pet my cat for 15 minutes when I got home, only if I had not engaged in overtime while I had been away from home. During Phase II, I would pet my cat for 15 minutes immediately after completing my overtime, and only if I had not exceeded my 30-minute limit. I additionally utilized a verbal-symbolic reinforcer that consisted of me telling myself “You did it” each night as I got ready to go to bed, and only if I had met my target for the day (Kafner & 6 I had considered telling my supervisor that I would be limiting my overtime, but I worried this would lead to a negative perception. Instead, I opted to respond by providing an estimate of when I would complete the task, which represented a positive, active response (i.e. saying I was do something, vs. saying I would not do something). 7 “Kirk to Enterprise. Enterprise? Enterprise, come in. Kirk to Enterprise” 8 My younger cat. 9 I had intended to use shoulders massages from my husband at bedtime as a reinforcer, and did so during the first week of my intervention. However, I found this interrupted our bedtime routine, and I realized this may not always be available as a reinforcer since my husband sometimes falls asleep before I come to bed. Gaelick-Buys, 1991). This reinforcer was employed throughout Phase I and Phase II. Unlike alcoholism and drug addiction, workaholism is generally socially acceptable, often reinforced with praise, immediate and long-term economic rewards, and opportunities for career advancement (Gupta, 2005; Schaufeli et al., 2006; Stoner et al., 2009). Stoner et al. (2009) describe that some organizations may deliberately extend these rewards to encourage overtime work. While I have not benefitted from immediate economic rewards10, engaging in the target behaviour has provided me with skills development (e.g., management experience) that may qualify me for higher paying positions in the future. My target behaviour has also been consistently reinforced with praise from my supervisor and staff. These reinforcers were more complex, and I do not feel I was able to sufficiently address them in this project. Some of the disputations and rational restructuring comprising my self-talk variable were developed to provide direct responses to these; for instance, reminding myself that I work hard and produce quality work that has been acknowledged in my performance reviews. To rearrange the reinforcer of perceived long-term higher income and career advancement potential, my self-talk focused on associating future opportunities with a different job and a career change, and that I have already acquired the skills, experience and reputation that may lead to these future opportunities, so continuing to engage in the target behaviour may not enhance these potential rewards. However, while this strategy may have helped address the target behaviour as it is associated with my current job, there is a risk that I may experience a relapse once I move on to a new job, especially one with greater responsibilities, that presents a high-risk situation. I anticipate that tacit expectation for overtime work might be an antecedent I encounter in a future job that could lead to relapse. I would plan to deal with this by continuing my modification of environment and self-talk/self-instruction strategies in order to enforce clear boundaries between the work and non-work areas of my life. 10 I do not receive overtime pay. My position is currently graded three pay grades lower than equivalent positions at the University of Alberta and elsewhere, due to the lowering of compensation and job evaluation benchmarks imposed in response to institutional budget cuts. Tangential activity reinforcers for reducing my target behaviour were the increased time I had available to spend with my daughter (improving our relationship) and on my course work. Withdrawal Data collection ended with a two-week period starting in Week 13 during which the independent variables were withdrawn. By the end of Week 12, the Phase II sub-goal and the major project goal had been achieved, and the reward collected (Watson & Tharp, 2007). Independent variables were withdrawn to evaluate whether the redefined antecedents were sufficient for maintaining the modified target behaviour, and whether self-change had been successfully achieved. Recordings in my structured journal continued through the withdrawal period. Results Daily and weekly overtime data for baseline, Phase I and Phase II are shown in Table 2. Means were calculated, along with percent change. Table 3 shows isolated data for Phase II and the withdrawal period, including means and percent change. During Week 8, 9 and 10 I was recovering from an eye infection/injury, and therefore avoided working overtime as much as possible in order to minimize eyestrain that may have impeded my recovery11. Since this may represent a confounding variable, I excluded Week 8, 9 and 10 data from my analyses. Phase II, therefore, spanned only three weeks, not the six weeks originally planned. During the baseline period I worked an average of 12.23 hours of overtime per week. A net change of -8.73 hours per week (-74.82 minutes per day) of total overtime was observed between baseline and Phase II, representing a 71% drop in overall overtime hours worked. Overtime worked outside my home was virtually eliminated (97% reduction), and overtime worked at home decreased by approximately one-third (64% reduction). 11 I utilized self-instruction and self-talk during these weeks to help me avoid the target behaviour, and to help manage anxiety due to not engaging in overtime. I stayed out of our library at home, so that the chair in the cat’s corner of the library would not cue the target behaviour. I also advised my supervisor that I would be minimizing my overtime during these weeks due to my eye infection/injury, which helped me manage the antecedent of perceived expectation of overtime work. During Week 11, I felt some pressure to work overtime in excess of my 30 minute time limit, to make up for the overtime work I had missed while recovering from my eye infection/injury through Week 8, 9 and 10. However, I only missed my daily target once during this week; I worked 60 minutes of overtime on the Monday of Week 11. Interestingly, overtime worked at home decreased during Phase I, though it was not specifically targeted during that period and independent variables were not implemented within the home domain. The act of monitoring/recording may have facilitated greater awareness of overtime work levels that led to an unintended reduction in overtime hours during Phase I, and this may also explain the slight downward trend observed through the baseline period (Figure 1). Latent effects of my self-talk/self-instruction variable implemented outside my home during Phase I may also explain the decreases in at home overtime observed during Phase I. After excluding my data for Weeks 8, 9 and 10, I was surprised to find that my mean overtime for Phase II exactly matched my target of 3.50 hours per week (30.00 minutes per day)! However, there was some variability in the weeks comprising Phase II. In Weeks 7, 11 and 12, I worked a total of 4.50, 4.00 and 2.00 overtime hours, respectively (Table 2). Nonetheless, I was able to achieve my major goal for this project by the end of Phase II. This was helped by a spontaneous sub-goal (unrewarded) I implemented during Week 12; namely, I decided I would not work overtime at all during that weekend (Easter weekend) so that I could spend time with my family (an incompatible behaviour). Table 2 shows a slight increase in overtime hours worked when the independent variables were withdrawn during the two-week withdrawal period, and may represent a relapse. A net change of +0.67 hours (+5.71 minutes) was observed. However, this data is confounded by a single day in Week 13 during which I worked four hours of overtime to deal with a specific crisis that arose at work (this was during a vacation day while I was travelling). Otherwise, my levels of overtime work continued to decrease through the withdrawal period. Table 3 shows withdrawal period data that excluded the “crisis” day, with comparison to Phase II. A net difference of -1.32 hours (-10.00 minutes) was observed. Table 2 Mean Daily and Weekly Overtime Baseline Phase I Overtime Worked Phase II* Overtime Worked Withdrawal Period Overtime Worked (% change from baseline) (% change from baseline) (% change from baseline) Daily Mean (minutes) Overtime worked outside of home 24.64 5.36 (-78.25%) 0.71 (-97.12%) 10.00 (-59.42%) Overtime worked inside home 80.18 57.86 (-27.84%) 29.29 (-63.74%) 25.71 (-67.93%) 104.82 63.21 (-39.70%) 30.00 (-71.38%) 35.71 (-65.93%) Overtime worked outside of home 2.88 0.63 (-78.14%) 0.08 (-97.22%) 1.17 (-59.37%) Overtime worked inside home 9.36 6.75 (-27.84%) 3.42 (-63.46%) 3.00 (-67.95%) 12.23 7.38 (-39.66%) 3.50 (-71.38%) 4.17 (-65.90%) Total Weekly Mean (hours) Total *excludes Weeks 8, 9 and 10 Although I attempted to completely withdraw my independent variables during this twoweek withdrawal period, I found that unintended unspoken self-talk occurred. This likely contributed to the continuing decrease in overtime observed during the withdrawal period (Table 3). Table 3 Mean Daily and Weekly Overtime, Phase II and Withdrawal Period, Excluding Data for “Crisis” Day During Withdrawal Period Phase II* Overtime Worked Withdrawal Period Overtime Worked Change from Phase II Minutes/Hours (% change) Overtime worked outside of home 0.71 1.54 +0.83 (+16.90%) Overtime worked inside home 29.29 18.46 -10.83 (-36.98%) 30.00 20.00 -10.00 (-33.33%) Overtime worked outside of home 0.08 0.17 +0.09 (+12.5%) Overtime worked inside home 3.42 2.0 -1.42 (-41.52%) 3.50 2.18 -1.32 (-37.71%) Daily Mean (minutes) Total Weekly Mean (hours) Total *excludes Weeks 8, 9 and 10 A consistent downward trends in overtime hours (total, and in each location domain) is depicted in the linear graph in Figure 1. Levels of overtime worked outside my home remained relatively stable after having been virtually eliminated in Phase I. Levels of overtime worked at home decreased consistently through Phases I and II, leveling off in Phase II as I neared my 30 minutes daily overtime maximum target. The gap between low and high weekly overtime levels also narrowed, leveling off mid-way through Phase II. A minor relapse in Week 6 occurred in response to a specific external deadline I had to meet at work, namely, submission of a grant application. If not for this, the decrease in overtime levels between Week 5 and Week 12 would have been steady and with little variance between high and low overtime levels. This graph also depicts the relapse that occurred during the withdrawal period (Week 13), though this was followed by a continuing downwards trend that returned overtime levels (total, and in each location domain) back to levels consistent with those achieved in Phase II. Despite feeling pressure to “catch up” due to overtime work missed during Week 8, 9 and 10, overtime levels observed for Week 11 varied little from levels observed for Week 7. Figure 1 Change in Overtime Hours Worked Through Baseline, Phase I, Phase II and Withdrawal Periods 18.00 Baseline Phase I Phase II Withdrawal 16.00 14.00 H 12.00 O 10.00 U R Total Weekly Over8me in Hours Total Weekly Over8me in Hours (Outside of Home) 8.00 6.00 Total Weekly Over8me in Hours (At Home) S 4.00 2.00 0.00 Week Week Week Week Week Week Week Week Week Week Week 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11 12 13 14 Change in Antecedents and Consequences Information from my structured journal reflected a substantial shift in the antecedent cues for my target behaviour. Notably, antecedents comprising negative thoughts and feelings through the baseline period were largely replaced by environmental cues by the end Phase II and through the withdrawal period. Table 4 provides some examples excerpted from my structured journal. Table 4 Structured Journal Excerpts: Examples of Antecedents and Consequences Surrounding Incidence of Overtime Work During Baseline, Phase II and Withdrawal Period Antecedents Finished dinner, have 90 minutes before daughter goes to bed Environmental Cues Sitting alone in waiting area during daughter’s dance class Check work email, see an email from supervisor requesting me to do a task Baseline If I don’t work overtime, I will lose my job. I’m scare of losing everything and not being able to take care of myself. I know my boss is working right now, and I know she will have something she wants me to do. If I don’t, she will think I am a slacker. Thoughts/ Feelings If I don’t do this work right now, my boss will give this opportunity to my colleague. I’m feel like I can’t compete. Finished dinner, have 90 minutes before my daughter goes to bed. Environmental Cues Phase II Self-instructions to start and end 30 minutes of overtime, iPhone alarm. Chair in the “cat’s corner” Thoughts/ Feelings Grant application deadline. I must work overtime so that I can meet this deadline, or else I will be in trouble. Feeling pressure to check work email, but it’s not my scheduled time for overtime Positive self-talk Finished dinner, have 90 minutes before my daughter goes to bed. Withdrawal Period Environmental Cues Chair in the “cat’s corner” Checked work email and found a crisis waiting for me Thoughts/ Feelings Worried because I’m not at the office. What am I missing? I should check-in. Consequences • Ran out of time. Didn’t have time to read my daughter a bedtime story. • Rushed to make her lunch, threw in some processed food. • Felt angry that I had let work get in the way. • My boss will be pleased that I did this work tonight, though. • Glad I had time to respond to an email from my boss. My fast response will impress her. • Was engrossed in work, didn’t talk to other parents when they showed up. • Worried they must have thought I was rude. • Continued working on some t asks after we got home. Didn’t have time to put the laundry in. • Stayed up until 12:30 a.m. working. • Angry that I didn’t have time for course work. • Woke husband up when I went to bed. • Had trouble falling asleep, was thinking about work, was angry I worked so late. • Glad I checked my email. My boss had some questions. She will be pleased that I answered her so quickly. • Won’t have time to finish all my course readings tonight, though. • Wasted time looking for emails that I had already sent to my boss. She should be able to find these on her own. Why do I have to suffer because my boss is disorganized? • Felt angry because I didn’t have time to help my daughter with her reading homework. My daughter won’t get her badge this week. • Worked until 11:00 pm, then laid awake until 3:30 am worried that I didn’t do enough work on it. • Glad that I caught t his opportunity, though. • Felt angry because I knew I would be exhausted the next day, and would have to continue working on this task. • Didn’t check my email again after my 30 minutes of overtime were up. • I know what tasks I have to do at work tomorrow. I know I will finish them tomorrow, and that they won’t be expected sooner. • Don’t feel anxious about ending my overtime for the night. • Able to schedule personal/family tasks: • Had time to go to the grocery store, as planned • Made some bracelets with my daughter. • Had time to finish my course readings for this week. • I don’t feel rushed. I don’t feel exhausted. • Worked my 30 minutes of overtime, then stopped. Was glad to get away from the litter box! • Worked more than my allotted 30 minutes of overtime. • Had to rush with everything else tonight. • Don’t feel anxious about ending my overtime for the night. • Didn’t check e-mail. • Played a game on my iPhone instead. • Didn’t check my email again after my 30 minutes of overtime were up. • I know what tasks I have to do at work tomorrow. I know I will finish them tomorrow, and that they won’t be expected sooner. Don’t feel anxious about ending my overtime for the night. • I don’t feel rushed. I don’t feel exhausted. • Had time to read the info package and fill out the forms the school had sent home. • Had time to do some gardening • Watched cat fail videos on YouTube with my daughter • Worked my 30 minutes of overtime, then stopped. Was glad to get away from the litter box! • Lost half a vacation day working, when I should have been spending time with my family. • Work was on my mind all day, but I tried not to think of other things. • Packed my iPhone in a bag in the back of the car where it wasn’t tempting me. • Turned on a CD and sang with my daughter. • Checked email. Didn’t find much. Wrote a few quick responses. • Now I can spend time with my family without worrying about work. Discussion My baseline overtime average of 12.23 hour per work excluded time spent working through break times during normal work hours. If work during break times had been included, this could have added up to 7.5 hours per week, increasing the weakly average to as much as 19.73 hours. This is almost triple the overtime rates reported by more than half the respondents in the 2012 National Survey on Balancing Work and Caregiving in Canada (Duxbury & Higgens, 2012). Technology was highlighted as an important factor mediating overtime engagement. The majority of survey respondents reported they spend at least one hour per non-work day on work e-mail, while 28% and 36% reported that using e-mail has increased their stress level and daily workload, respectively (Duxbury & Higgens, 2012). Although the sample comprising this survey is not representative of the general population (Duxbury & Higgens, 2012), my own educational attainment, socioeconomic status and job type coincide with the described characteristics of this sample. Using combined self-talk / self-instruction and modification of environment as independent variables in this project, I achieved an overall 71% reduction in overtime hours worked outside of my regular work hours. This change persisted through a two-week period during which the independent variables were withdrawn, indicating I succeeded in modifying relationships between antecedents and the target behaviour, and success in my self-change goal overall. Information from my structured journal affirms these antecedents have been redefined, and the consequences recorded demonstrate a qualitative change in my perceptions towards overtime work. As I progressed through Phases I and II, I took successively greater control over my overtime. Looking at a sample of Dutch workers, Beckers et al. (2008) found involuntary overtime was associated with high fatigue and low job satisfaction with workers being at risk for burnout, while voluntary overtime was associated with non-fatigue and job satisfaction even when overtime was not directly compensated. In terms of fatigue, this is consistent with my experience, as demonstrated by the consequences recorded in my structured journal through Phases II the withdrawal period. My overall job satisfaction did not increase, however. While my structured journal indicates decreased work-home interference (Jansen et al, 2004) and feelings of increased control over overtime, increased job satisfaction was not observed. This may be explained by my overarching desire for a career change. The most important outcome may be that the compulsion component characterizing my overtime work began to be replaced with self-control over the target behaviour (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Apart from some very specific circumstances (e.g., external deadlines; being away from the office for an extended period of time being confronted with a crisis), my data suggest I generally moved from a state of uncontrolled, involuntary overtime influenced by external factors, to a state of self-controlled, voluntary overtime. This suggests the independent variables effectively addressed addictive / psychosocial dynamics that may have been underlying my target behaviour. In terms of qualitative change, working overtime was associated with asserting independence at the outset of this project, and I was able to render this association so that my capacity to control (limit) my own overtime represented an assertion of independence. The links to prior experiences of unpredictable income and economic adversity were mooted through positive self-talk that highlighted the mediating effects of long-term employment and income stability, as well as acquired qualifications and future career prospects. The results of my project suggest strategies that may be effective in treating work addiction stemming from unpredictable employment status in other situations. In response to Rowlands and Handy (2012), for the New Zealand film industry workers described in their study, self-talk might be utilized to help redefine independence as being a product of an individual’s entire portfolio of work, not their current employment status. Furthermore, stimulus narrowing might be utilized to strengthen the association between periods of unemployment and opportunities to engage in personal creative projects that provide for skills maintenance/development and portfolio development. Thus, periods of unemployment would come to embody rewards similar to those experienced during periods of employment. Characteristics of my overtime work straddled three of the workaholism categories proposed by Robinson (1998). My data indicate a potential case of workaholism that involves high work engagement and high work completion, characteristics that Robinson (1998) classifies in separate categories. My case may therefore suggest a new category is needed, one that perhaps accounts for the roles of voluntariness and organizational culture in the development of workaholism as a maladaptive response. Exploring this might be a goal for future research. Limitations Declines in overtime recorded during my baseline period and in Phase I hint at an important limitation; namely, surveillance may have been a factor in achieving my project goals (Watson & Tharp, 2007). This project was completed as part of a course that required updated data to be posted to a peer forum each week, and was completed as an assignment worth 50% of the course grade. Surveillance was therefore an inherent aspect of this project and course. Surveillance has been a component of the weight management program I am enrolled in, in that case deliberately incorporated as an independent variable. I utilize a journal to record and reflect on my daily calorie in-take, and a dietitian reviews this journal with me at each appointment. Similarly, the ease with which I seem to have been able to reduce my target behaviour suggests achievement of my project goals was mediated by an external variable not wholly under my control; namely, obligations imposed by the course requirements. My motivation for undertaking this self-modification project in the first place was to satisfy the course requirements, complete the course, and be one step closer to completing my degree. If I had undertaken this selfmodification project outside of this course (or without obligation), my motivation might have faltered, and my results might have been quite different. Although I note these factors as limitations in the present project, an objective for future research might be to assess the potential for surveillance as a treatment for workaholism. It is unclear how Week 8, 9 and 10 might have impacted my results. During these weeks, I experienced no negative impacts (other than my own anxiety) from not engaging in overtime. If a longer timeframe for this project had been available to me, I might have added a brief washout phase after Week 10 before resuming Phase II, to help eliminate any lingering effects of Weeks 810, at least to point where target behaviour data had returned to levels consistent with those recorded during Week 7. This project may have been strengthened by including the overtime I work through my break times during my regular work hours, as these incidences may involve different psychosocial dynamics that may have been relevant to the present project if they had been identified, or that may contribute to long-term risk of relapse. In other words, the psychosocial aspects of my overtime work compulsion may have been more fully addressed if this other component of my overtime work had been explored. I would consider this as an objective for future research. I might also consider exploring different self-talk content that excludes focus on skills development and higher income as long-term rewards for engaging in overtime in the present, as this content may persist as a reinforcer for the target behaviour in high risk situations such as a future job. References Albertsen, K., Rafnsdóttir, G. L., Grimsmo, A., Tómasson, K., and Kauppinen, K. (2008). Workhours and worklife balance. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, Suppl.(5):14–21. Retrieved from www.sjweh.fi/download.php?abstract_id=1235&file_nro=1 Alini, E. (2011, October) Rank your income: Where do you stand compared to the rest of Canada? Maclean’s. [Web article]. Retrieved from http://www.macleans.ca/economy/economicanalysis/rank-your-income-where-do-youstand-compared-to-the-rest-of-canada/ Beckers, D. G. I., van der Linden, D., Smulders, P. G., Kompier, M. A., Taris, T. W., and Geurts, S. A. E. (2008). Voluntary or involuntary? Control over overtime and rewards for overtime in relation to fatigue and work satisfaction. Work & Stress: An International Journal of Work, Health & Organisations, 22(1), 33-50. doi:10.1080/02678370801984927 Beckers, D. G. I., van der Linden, D., Smulders, P. G., Kompier, M. A., Taris, T. W., and Van Yperen, N. W. (2007). Distinguishing between overtime work and long workhours among full-time and part-time workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 33(1), 37-44. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40967619 Breen, R. B., Kruedelbach, N. G., and Walker, H. I. (2001). Cognitive changes in pathological gamblers following a 28-day inpatient program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours, 15(3), 246-248. Cherry, M. (2004). Are salaried workers compensated for overtime hours? Journal of Labor Research, 25(3). 485-494. Retreived from http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s12122-004-1026-5.pdf Duxbury, L., & Higgens, C. (2012). National Study on Balancing Work and Caregiving in Canada. Retrieved June 8, 2014, from http://newsroom.carleton.ca/wpcontent/files/2012-National- Work-Long-Summary.pdf Gupta, V. S. (2005). International communication: Contemporary issues and trends in global information revolution. New Delhi, India: Concept Publishing Company. Retrieved from http://books.google.ca/books?id=M5AOSZsGx18C&pg=PA49&lpg=PA49&dq=24hour+society&source=bl&ots=06sq8Qy122&sig=NVEpZ3qpRiczY6XrMMQruuxybo8&hl =en&sa=X&ei=itChU8TEBdKFogSVtoKIDQ&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAzge#v=onepage&q=24 -hour%20society&f=false Haber, S. E., and Goldfarb, R. S. (1995). Does salaried status affect human capital accumulation? Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48(2), 322-37. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/2524490 Jansen, N. W. H., Kant, I., Kristensen, T. S., and Nijhuis, F.N.J. (2003). Antecedents and Consequences of Work–Family Conflict: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 45, 479–491. Jansen, N. W. H., Kant, I., Nijhuis, F. J. N., Swaen, G. M. H., and Kristensen, T. S. (2004). Impact of worktime arrangements on work-home interference among Dutch employees. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 30(2), 139-148. doi:10.5271/sjweh.771 Kafner, F. H., and Gaelick-Buys, L. (1991). Self-management methods. In F. H. Kafner & A. p > Goldstien (Eds.), Helping people change: A textbook of methods (4th ed.) (pp. 305-360). New York: Pergamon Press. Krietzman, L. (1999). The 24-hour society. London, England: Profile Books Ltd. Maslach, C., Schaufeli,W. B. and Leiter, M. P. (2001), ‘Job burnout’. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. McConaghy, N., Blaszczynski, A., and Frankova, A. (1991). Comparison of imaginal desensitisation with other behavioural treatments of pathological gambling. A two- to nineyear follow-up. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 390-3. Mueller, A., Mueller, U., Silbermann, A., Reinecker, H., Bleich, S., Mitchell, J. E., & de Zwaan, M. (2008). A randomized, controlled trial of group cognitive-behavioral therapy for compulsive buying disorder: posttreatment and 6-month follow-up results. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(7), 1131-1138. Porter, G. (1996). Organizational impact of workaholism: suggestions for researching the negative outcomes of excessive work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1, 70–84. Porter, G. (2004). Work, work ethic, work excess. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17, 424–39. Robinson, B. E. (1998). Chained to the desk: A guidebook for workaholics, their partners, and children, and all the clinicians who treat them. New York, USA: New York University Press. Rowlands, L., and Handy, J. (2012). An addictive environment: New Zealand film production workers’ subjective experiences of project-based labour. Human Relations, 65(5), 657680. Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., and Bakker, A. B. (2006). Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? On the differences between work engagement and workaholism. In R. J. Burke (Ed.), Research companion to working time and work addiction, (pp. 193-217). Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK. doi:10.4337/9781847202833 Schneider, B., and Waite, L. J. (2005). Being together working apart: Dual-career families and the work–life balance. New York: Cambridge University Press. Scott, K.S., Moore, K.S. and Miceli, M.P. (1997). An exploration of the meaning and consequences of workaholism. Human Relations, 50, 287–314. Seligman, M. E. P. (1998). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. New York: Pocket Books. Skinner, N., and Pocock, B. (2008). Work-life conflict: Is work time or work overload more important? Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 46(3), 303-315. Stoner, C. R., Stephens, P., and McGowan, M. K. (2009). Connectivity and work dominance: Panacea or pariah? Business Horizons, 52(1), 67-78. doi: 10.1225/BH311 Van Wijhe, C., Schaufeli, W. B., and Peeters, M. C. W. (2010). Understanding and treating workaholism: setting the stage for successful interventions. In R. J. Burke, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Risky business: Psychological, physical and financial costs of high risk behavior in organizations (pp. 107--134). Farnham, England: Gower. Retrieved from http://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/335.PDF Walters, G. D. (2000). Behavioral self-control training for problem drinkers: A meta-analysis of randomized control studies. Behavioral Therapy, 31, 135-149. Watson, D. L., and Tharp, R. G. (2007). Self-directed Behaviour (9th Edition). Belmont, USA: Wadsworth.