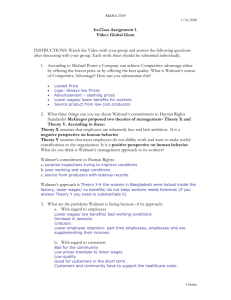

empire of efficiency - ETH E

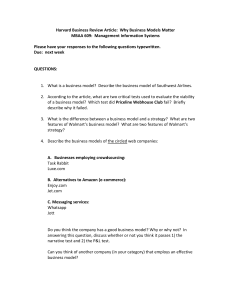

advertisement