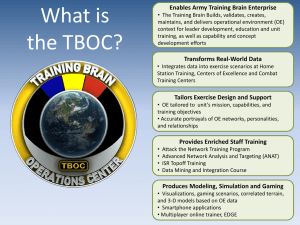

Command, Control, and Troop

advertisement