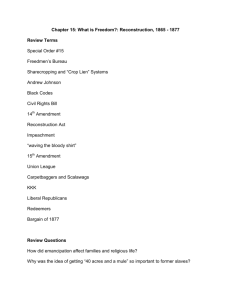

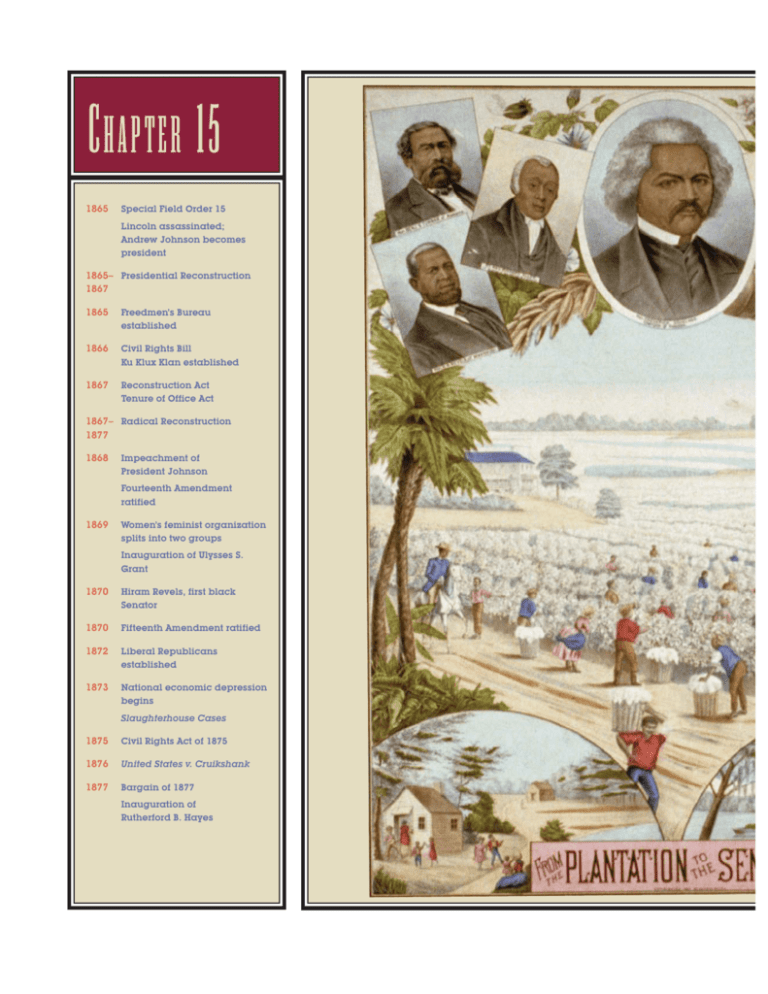

the meaning of freedom

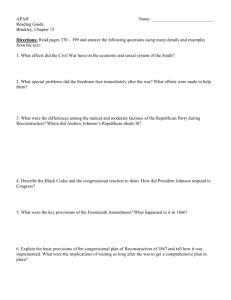

advertisement