South Germany, England, Venice, Antwerp.

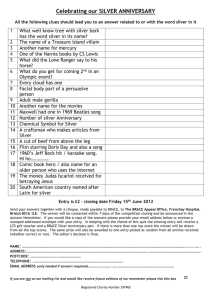

advertisement