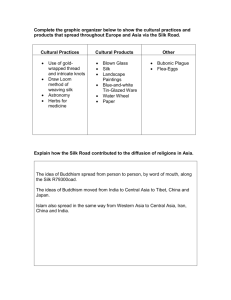

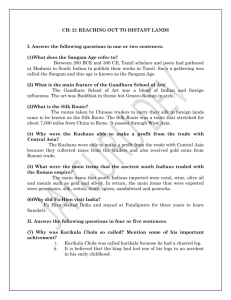

4. Religions Along The Silk Roads

advertisement