Epidural Anesthesia for a Parturient with Superior Vena Cava

advertisement

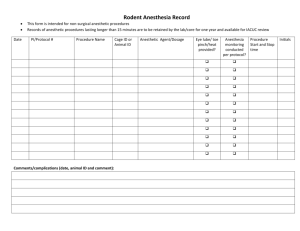

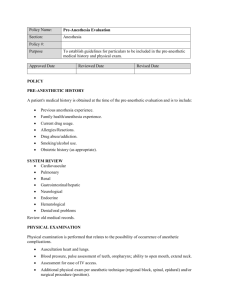

LO Jİ V E R E A N N EĞ RK YO N DE R İ TÜ Olgu Sunumu İ AS A N ES TE ZİY O M Türk Anest Rean Der Dergisi 2012; 40(1):52-57 doi:10.5222/JTAICS.2012.052 Epidural Anesthesia for a Parturient with Superior Vena Cava Syndrome Serhan Yurtlu, Sedat Hakimoğlu, Volkan Hancı, Hilal Ayoğlu, Gülay Erdoğan, Işıl Özkoçak Zonguldak Karaelmas Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Anesteziyoloji ve Reanimasyon Anabilim Dalı SUMMARY Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) is an anesthetic challenge because of its symptomatic cardiovascular, respiratory and neurologic pathophysiology. Decreased venous return to the heart, potential negative outcome of positive pressure ventilation in the presence of an intrathoracic mass complicate the anesthetic management. If this syndrome develops during pregnancy, this condition becomes more dreadful because of already existing pressure on inferior vena cava by gravid uterus. In this case report, we aimed to present anesthetic management of a parturient with SVCS and endobronchial tumour. Key words: Superior vena cava syndrome, cesarean, epidural anesthesia ÖZET Süperior Vena Kava Sendromu Olan Gebede Epidural Anestezi Süperior vena kava sendromu (SVKS) semptomatik kardiyovasküler, solunumsal ve nörolojik patofizyolojisinden dolayı anestezi açısından karmaşık bir durumdur. İntratorasik kitlenin varlığında kalbe azalmış venöz dönüş, pozitif basınçlı ventilasyonun olası negatif etkileri ile birlikte durumu daha da karmaşık hale getirir. Eğer sendrom hamilelik sırasında görülürse inferior vena kava üzerinde de mevcut olan uterus basıncının etkisiyle durum daha da kötüleşir. Bu olgu sunumunda SVKS ve endobronşiyal tümörü olan bir gebede anestezi yönetimimizi sunmayı amaçladık. Anahtar kelimeler: Süperior vena kava sendromu, sezaryen, epidural anestezi J Turk Anaesth Int Care 2012; 40(1):52-57 Alındığı Tarih: 23.12.2010 Kabul Tarihi: 09.03.2011 Yazışma adresi: Doç. Dr. Volkan Hancı, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Anesteziyoloji ve Reanimasyon Anabilim Dalı, ÇOMU Uygulama Araştırma Hastanesi, Merkez Ameliyathaneleri, Kepez, Çanakkale e-posta: vhanci@gmail.com 52 S. Yurtlu ve ark., Epidural Anesthesia for a Parturient with Superior Vena Cava Syndrome INTRODUCTION CASE Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) is a common complication of malignancy, especially of lung cancer and lymphoma.(1) Patients may present with several symptoms which in decreasing order of frequency include facial and neck swelling, arm swelling, dyspnea, cough, and dilated chest veins.(1) The patient was a 32 y/o G2, P1 parturient at 31. gestational week who presented at our obstetrics and gynecology service for progressively increasing dyspnea. Her cough and dyspnea had begun one month before and she had been given symptomatic treatment previously at an another hospital. Initially, pneumonia was suspected, antibiotic therapy was initiated combined with a mucolytic, and tests were performed to rule out tuberculosis. Despite treatment, the dyspnea was not relieved, and clinically evident SVCS presented on the 6th day of her hospitalization. She had bilaterally dilated veins on the neck, upper part of chest wall and arm sweling especially on the right. Chest radiograph has shown total atelectasia of the right lung, mediastinal enlargement and deviation of trachea to the left (Figure 1). Thoracic and abdominal magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large anterior mediastinal (85x60 mm), and a relatively smaller endobronchial mass (40 mm) occluding the right main stem bronchus, and lesions within the parenchyma Worrisome signs include stridor, as an indicative of laryngeal edema, and as confusion, obtundation which might indicate cerebral edema. An ominous sign in our patient was stridor, suggesting tracheal compression by an anterior mediastinal mass. Presence of respiratory and neurologic compromise can be associated with serious or fatal outcomes in SVCS.(1) If SVCS occurs during pregnancy, the symptoms are worsened by the physiologic changes of pregnancy, especially pressure on the inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus, which has an additive effect on the impaired venous return because of compression of the superior vena cava.(2,3) Due to rarity of the condition, there are only a few cases in the literature reporting anesthetic approach to the parturients with SVCS.(2,3) Optimal anesthetic management for the parturient with SVCS remains to be determined.(2) In this case report, we present our anesthetic approach to a parturient in whom SVCS coexist with total obstruction of right main stem bronchi, a highly life threatening condition, managed with epidural anesthesia. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient for publication. Figure 1. Antero-posterior chest radiograph showing large mediastinal tumor deviating the thrachea and complete atelectasia of the right lung. 53 Türk Anest Rean Der Dergisi 2012; 40(1):52-57 Figure 2. Thoracic magnetic resonance imaging showing near complete obstruction of superior vena cava. of the left lung and liver (Figure 2). Our obstetric team decided that cesarean section was indicated to preserve the life of the mother. Fetus was 32 weeks old at the time of scheduled cesarean delivery The results of the preoperative arterial blood analysis of the patient under ambient conditions were as follows; pH: 7,48, pO2: 69 mmHg, pCO2: 29 mmHg, HCO3: 21 mEq/L. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated a minimal pericardial effusion, ejection fraction of 60 %, and no evidence of intracardiac tumour or thrombosis. Because of the potential morbidity associated with positive pressure ventilation in the presence of a symptomatic anterior mediastinal mass, regional anesthesia was chosen. Upon arrival into the operating room two intravenous cannulas were inserted, one to the left arm, the other to the right leg from dorsal aspect of the foot. Infusion of lactated Ringer’s solution was started at approximately 15 mL kg-1 hr-1. Radial arterial cannulation was performed on the left arm, revealing arterial blood pressure 54 of 130/80 mmHg. The patient was placed in the left lateral position to avoid further aortocaval compression. The epidural space was identified at the L3-4 level using loss of resistance technique by saline injection. Catheter was easily inserted into epidural space and fixed to skin with an epidural clamp (SIMS Portex®, Hythe, UK). Negative aspiration is confirmed and a test dose of 3 mL of 2 % lidocaine containing 200.000-1 epinephrine was given. Since a sensory block at T4 level was reported to be obtained with 15 mL of local anesthetic-opioid mixture in a similar patient(2), we injected 12 mL of additional local anesthetic-fentanyl mixture (20 mL 0.5 % levobupivacaine plus 100 µg fentanyl) with a slow, incremental injection technique.(2,4) At the 10th minute of injection, bilateral sensory block at T10 level was obtained. In order to achieve sensory block at T4 level, 5 mL of local anesthetic-opioid mixture was injected 2 times, and finally 5 mL 0.5 % levobupivacaine administered through the epidural catheter. Injection of local anesthetics was completed in 30 minutes. Upper level of sensory block was T8 at the end of 35 minutes, and it didn’t rise any further during the monitorization. Fetal heart rate remained within normal limits during this period. Maternal hemodynamics was essentially stable with no need for sympatomimetic drug or atropine. Surgery was uneventful until peritoneal closure, and the patient was totally pain free. Neonate’s Apgar score at 1st and 5th minute were 9 and 10 points, respectively, fetal blood pH obtained from umblical cord was 7.37. When peritoneal closure was performed, we administered supplementory intravenous fentanyl (100 µg in two divided doses) and propofol (50 mg, in total, multiple administrations) because the patient felt pain at her right upper shoulder. Spontaneous ventilation S. Yurtlu ve ark., Epidural Anesthesia for a Parturient with Superior Vena Cava Syndrome was maintained at all times. There were no intervals of apnea or need for positive pressure ventilation. Just after the end of surgery, diagnostic bronchoscopy with topical anesthesia utilizing lidocaine is performed at the operation theatre, and a endobronchial tumour totally obstructing right main bronchi at carinal level was seen. During bronchoscopy biopsy material was taken by pulmonologists for histopathological diagnosis. Since the diagnosis was an endobronchial tumour, our obstetric team decided to start anticoagulant prophylaxis consisting of 0.4 mL enoxaparin administered subcutaneously. Therefore, we decided to administer a single dose of 3 mg epidural morphine and remove the catheter for safety of the anticoagulant therapy. Epidural morphine was given at the second postoperative hour, and the catheter was removed. Anticoagulant therapy was initiated for 2 hours after the catheter removal.(5) After an uneventful first postpartum day, the patient was transferred to the Pulmonary Service, anti-edema therapy was initiated and the patient was prepared for radiation therapy for palliation of SVCS. Shortly after, symptoms were greatly improved. Diagnostic testing revealed that SVCS was a consequence of an aggressive malignant mesenchymal tumor of the lung. Unfortunately, the patient died one month after the delivery. DISCUSSION Intrathoracic tumour does not always lead to SVCS but it is a common complication of malignancy. Malignancies in pregnancy occur in 1.000-1 of all pregnancies, and parturients with intrathoracic tumors are less frequently encountered.(2) There have been less than 50 cases of lung cancer in pregnancy reported to date.(6) Intrathoracic tumor results in SVCS in 2-4 % of the patients at some point during the course of the disease. This makes the circumstances of our patient truly unusual, and the anesthetic management issues challenging. Previous reports indicate that general anesthesia is associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates in patients with SVCS.(7-10) Anterior mediastinal mass combined with obstruction of superior vena cava can present a challenge for general anesthesia because of severe hemodynamic compromise secondary to compression of the heart and great vessels. Positive pressure ventilation will exacerbate hemodynamic instability by increasing intrathoracic pressure, rapidly decreasing venous return, and potentially compromising an already narrowed airway related to the physiologic changes of pregnancy.(2,11) Intraoperative mortality secondary to cardiac compression without any evidence of tracheal obstruction mediastinal masses has been reported.(2,8,12) General anesthesia should be avoided, because of the risk of difficult mask ventilation, difficult intubation, airway edema, and paralysis of the vocal cords postoperatively.(2,8) Two reported cases demonstrated use of epidural anesthesia in parturients with SVCS, resulting in good outcomes.(2,3) Their favourable outcomes suggest epidural anesthesia as a method to ensure a good outcome. In both of these reports only 15 mL of local anesthetic was necessary for obtaining T4 level of sensory blockade. Use of epidural anesthesia has been reported for cesarean section in a 55 Türk Anest Rean Der Dergisi 2012; 40(1):52-57 parturient with tracheal tumor.(13) On the other hand, spinal and continuous spinal anesthesia were used for parturients with intrathoracic masses without symptoms of SVCS.(14,15) The authors described successfully managed anesthetic course with both regimens. Patients and babies had done well with this techniques in those case reports.(13-15) Spinal and continuous spinal anesthesia have been used in parturients with intrathoracic masses without SVCS with good outcomes.(13-15) We did not select spinal anesthesia for our patient because sudden sympathectomy could have created serious hemodynamic compromise. Combined spinal-epidural technique wasn’t preferred since the incidence of hypotension is similar to spinal anesthesia.(16) We considered continuous spinal anesthesia to allow a slower onset, but we were unsure about the distribution of local anesthetics in the subarachnoid space related to SVCS.(3) We selected an epidural anesthetic to allow incremental injection and slow onset of pharmacological sympathectomy. The outcome of the epidural block was a surprise, with the sensory level never exceeding T8, despite a large volume of local anesthetic. We think that it could be the result of increased epidural pressure in our patient. Similarly, Kawamata et al.(17) shown an increase in baseline cervical epidural pressure up to 36 mmHg in a patient with SVCS syndrome. They had stated that after the development of SVCS, cervical epidural pressure had risen to 98 mmHg after injection of 6 mL local anesthetic, and epidural fluid flow changed its course to the caudal direction. This could explain the inability to move the sensory level above T8 in our patient.(17) 56 The low level achieved in this case despite large volume of local anesthetic suggests that high epidural pressure should be suspected in parturients with SVCS. Previous case reports had shown that, severe hemodynamic compromise secondary to compression of the heart and great vessels may occur in general anesthesia application for SCVS.(2,8,11,12) In our case report, hemodynamic parameters were almost unchanged during the induction and maintanence of epidural anesthesia. However hemodynamic parameters should be carefully monitorized in such patients. We conclude that, from the hemodynamic point of view, epidural anesthesia was well tolerated by our patient with SVCS, but its limitations about the upper level of sensorial block should be taken into consideration. REFERENCES 1. Wan JF, Bezjak A. Superior vena cava syndrome. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2009;27:243-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2009.01.003 PMid:19447309 2. Buvanendran A, Mohajer P, Pombar X, Tuman KJ. Perioperative management with epidural anesthesia for a parturient with superior vena caval obstruction. Anesth Analg 2004;98:1160-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000101982. 75084.F2 3. Chan YK, Ng KP, Chiu CL, Rajan G, Tan KC, Lim YC. Anesthetic management of a parturient with superior vena cava obstruction for cesarean section. Anesthesiol 2001;94:167-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000542-20010100000031 PMid:11135739 4. Fun W, Lew E, Sia AT. Advances in neuraxial blocks for labor analgesia: new techniques, new systems. Minerva Anestesiol 2008;74:77-85. PMid:18288070 5. Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Rowlingson JC, Enneking FK, Kopp SL, Benzon HT, Brown DL, Heit JA, Mulroy MF, Rosenquist RW, Tryba M, Yuan CS. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medi- S. Yurtlu ve ark., Epidural Anesthesia for a Parturient with Superior Vena Cava Syndrome cine Evidence-Based Guidelines (Third Edition). Reg Anesth Pain Med 2010;35:64-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181c15c70 PMid:20052816 6. Azim HA Jr, Peccatori FA, Pavlidis N. Lung cancer in the pregnant woman: to treat or not to treat, that is the question. Lung Cancer 2010;67:251-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.10.006 PMid:19896236 7. Tonnesen AS, Davis FG. Superior vena caval and bronchial obstructrion during anesthesia. Anesthesiol 1976;45:91-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000542-19760700000017 PMid:937758 8. Keon TP. Death on induction of anesthesia for cervical node biopsy. Anesthesiology 1981;55:471-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000542-19811000000028 9. Goh MH, Liu XY, Goh YS. Anterior mediastinal masses: an anaesthetic challenge. Anaesthesia 1999;54:670-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00961.x PMid:10417460 10.Northrip DR, Bohman BK, Tsueda K. Total airway occlusion and superior vena cava syndrome in a child with an anterior mediastinal tumour. Anesth Analg 1986;65:1079-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/00000539-19861000000019 11.Pullerits J, Holzman R. Anaesthesia for patients with mediastinal masses. Can J Anaesth 1989;36:681-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03005421 PMid:2490850 12.Levin H, Bursztein S, Heifetz M. Cardiac arrest in a child with an anterior mediastinal mass. Anesth Analg 1985;64:1129-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1213/00000539-19851100000017 13.Ng YT, Lau WM, Yu CC, Hsieh JR, Chung PC. Anesthetic management of a parturient undergoing cesarean section with a tracheal tumor and hemoptysis. Chang Gung Med J 2003;26:70-5. PMid:12656313 14.Martin WJ. Cesarean section in a pregnant patient with an anterior mediastinal mass and failed supradiaphragmatic irradiation. J Clin Anesth 1995;7:312-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0952-8180(95)00003-Z 15.Van Winter JT, Wilkowske MA, Shaw EG, Ogburn PL, Pritchard DJ. Lung cancer complicating pregnancy: case report and review of literature. Mayo Clin Proc 1995;70:384-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.4065/70.4.384 PMid:7898147 16.Thorén T, Holmström B, Rawal N, Schollin J, Lindeberg S, Skeppner G. Sequential combined spinal epidural block versus spinal block for cesarean section: effects on maternal hypotension and neurobehavioral function of the newborn. Anesth Analg 1994;78:1087-92. PMid:8198262 17.Kawamata M, Omote K, Sumita S, Iwasaki H, Namiki A. Epidural pressure in a patient with superior vena cava syndrome. Can J Anaesth 1996;43:1277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03013444 PMid:8955985 57