Successful Treatment of Superior Vena Cava Syndrome Induced by

advertisement

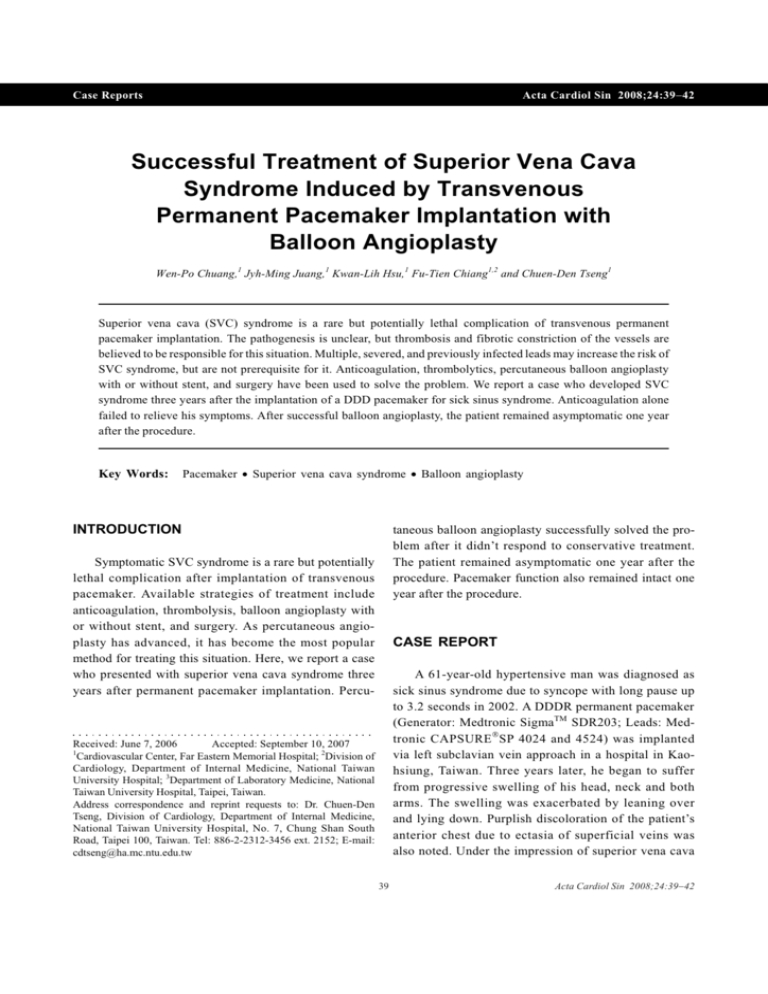

Case Reports Acta Cardiol Sin 2008;24:39-42 Successful Treatment of Superior Vena Cava Syndrome Induced by Transvenous Permanent Pacemaker Implantation with Balloon Angioplasty Wen-Po Chuang,1 Jyh-Ming Juang,1 Kwan-Lih Hsu,1 Fu-Tien Chiang1,2 and Chuen-Den Tseng1 Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome is a rare but potentially lethal complication of transvenous permanent pacemaker implantation. The pathogenesis is unclear, but thrombosis and fibrotic constriction of the vessels are believed to be responsible for this situation. Multiple, severed, and previously infected leads may increase the risk of SVC syndrome, but are not prerequisite for it. Anticoagulation, thrombolytics, percutaneous balloon angioplasty with or without stent, and surgery have been used to solve the problem. We report a case who developed SVC syndrome three years after the implantation of a DDD pacemaker for sick sinus syndrome. Anticoagulation alone failed to relieve his symptoms. After successful balloon angioplasty, the patient remained asymptomatic one year after the procedure. Key Words: Pacemaker · Superior vena cava syndrome · Balloon angioplasty INTRODUCTION taneous balloon angioplasty successfully solved the problem after it didn’t respond to conservative treatment. The patient remained asymptomatic one year after the procedure. Pacemaker function also remained intact one year after the procedure. Symptomatic SVC syndrome is a rare but potentially lethal complication after implantation of transvenous pacemaker. Available strategies of treatment include anticoagulation, thrombolysis, balloon angioplasty with or without stent, and surgery. As percutaneous angioplasty has advanced, it has become the most popular method for treating this situation. Here, we report a case who presented with superior vena cava syndrome three years after permanent pacemaker implantation. Percu- CASE REPORT A 61-year-old hypertensive man was diagnosed as sick sinus syndrome due to syncope with long pause up to 3.2 seconds in 2002. A DDDR permanent pacemaker (Generator: Medtronic SigmaTM SDR203; Leads: Medtronic CAPSURE Ò SP 4024 and 4524) was implanted via left subclavian vein approach in a hospital in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Three years later, he began to suffer from progressive swelling of his head, neck and both arms. The swelling was exacerbated by leaning over and lying down. Purplish discoloration of the patient’s anterior chest due to ectasia of superficial veins was also noted. Under the impression of superior vena cava Received: June 7, 2006 Accepted: September 10, 2007 1 Cardiovascular Center, Far Eastern Memorial Hospital; 2Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital; 3Department of Laboratory Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Dr. Chuen-Den Tseng, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, No. 7, Chung Shan South Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan. Tel: 886-2-2312-3456 ext. 2152; E-mail: cdtseng@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw 39 Acta Cardiol Sin 2008;24:39-42 Wen-Po Chuang et al. 12 ´ 40 mm was then used to dilate the lesion with pressure up to 10 atm. Due to recoil of the stenotic site, a Tyshak balloon 15 ´ 40 mm was then used to dilate it with 4 atm. After that, no more residual stenosis was noted. Also, the pressure of the right brachiocephalic vein dropped from 24 mmHg to 12 mmHg, which was equal to that of the right atrium. The patient’s symptoms were then relieved. He was discharged on wafarin and remained free of symptoms one year after the procedure. syndrome, enoxaparin (1 mg/kg q12h) was administered subcutaneously. Contrasted computed tomography of the thorax showed stricture of the superior vena cava with prominent collaterals in the perivascular, paratracheal and left upper chest walls (Figure 1). No definite hypodense filling defect was found in the SVC or brachiocephalic veins. Due to persistent symptoms after one week of anticoagulation, the patient was brought to our catheterization lab. Using the right femoral vein as vascular access, we retrogradely passed terumo wire through the stenotic site and brought a 6 Fr. multipurpose A2 catheter to the right brachiocephalic vein. Venography then showed stenosis at the SVC (Figure 2) just below the junction of the azygous vein and superior vena cava. A Smash balloon DISCUSSION Although around 30% of patient receiving transvenous permanent pacemaker implantation may have peripheral or central venous stenosis and occlusion, only 4 in 1000 to 3 in 10000 implants will develop superior vena cava syndrome.1,2 Multiple lead placement and previous infected or severed leads may increase the risk of SVC syndrome but aren’t prerequisite. This complication may occur as early as two days following pacemaker implantation or as late as 15 years after implantation. The pathogenesis is unclear. In those with early Figure 2. Venography (lateral view) obtained by injection of contrast from multipurpose catheter placed below the stricture site (arrows) of superior vena cava (A), in the azygous vein (arrow heads, B), and in the brachiocephalic trunk (C). Early snapshot during the inflation of balloon showed the tight stricture (D) which was fully dilated later. Figure 1. Computed tomography of thorax showed stricture of superior vena cava (arrowheads in A) and prominent collaterals in the perivascular, paratracheal (arrows in A) and left upper chest walls (arrows in B). Acta Cardiol Sin 2008;24:39-42 40 Angioplasty for Pacemaker Induced SVC Syndrome presentation, acute thrombosis was believed to be the cause. Fibrotic stenosis has been shown during surgery and autopsy and likely plays a role in chronic cases. Using intravenous ultrasound, intimal thickening was also demonstrated in one case report.3 The modalities of treatment for this situation include anticoagulation, thrombolysis, 4,5 endovascular treatment6-9 and surgery.10,11 Anticoagulation is reasonable for all patients as pulmonary embolism can occur in SVC syndrome caused by pacemaker and may be lethal. Anticoagulation alone is often not sufficient and is usually used in combination with other treatment modalities. However, some mild symptomatic cases may be managed only with anticoagulation therapy alone, even without opening the occluded vein. Successful long-term follow-up experience of conservative treatment has been reported.12 Thrombolysis is also used systemically or locally alone or in combination with percutaneous treatment.4 The early treatment appears to be the key to successful thrombolysis.5 If thrombolysis is given before the fifth day of occlusion, it can be effective in 88% of cases; but if the delay is longer than five days, only 25% of cases can be successfully treated. Surgical treatment consists of bypassing the stenosis with a polytetrafluoroethylene tube, autologous spiral vein or azygous vein. Long-term patency of spiral vein graft up to 15 years was reported. 11 Epicardial leads can also be placed during the operation if necessary. But the procedure’s relatively invasive nature led to its loss of popularity after the introduction of endovascular treatment.13 Angioplasty for SVC syndrome has been well documented in the literature.6,8,9,13 Restenosis due to elastic recoil may occur but is manageable by repeating angioplasty.14 Stents are usually placed if the lesions recoil despite repeated balloon angioplasty. Self-expandable stents are often preferred rather than balloon-mounted ones because they have larger diameter and are more flexible. They can adapt to the greater diameter of the vessel after the flow re-establishes, thus have lower risk for stent migration. Smayra et al. demonstrated that the 1-year patency rates after stenting of SVC syndrome for malignant, benign and hemodialysis patients were, respectively, 74%, 50% and 22%.6 Retraction of the pacemaker wire before the deployment of stents should be tried. Although the leads may be incorporated into the venous wall and not directly contact with stents, risk of damage of the lead is still a concern. Besides, once the pacemaker wire is dysfunctional, insertion of additional lead may further increase the risk of recurrent venous obstruction. Bolad et al. showed that it was feasible to perform lead extraction, angioplasty with or without stenting and re-implantation of new systems during one procedure. 7 Rupture of superior vena cava15 and stent migration to pulmonary artery 10 are possible serious complications of angioplasty for stenosis of superior vena cava. In our case, fibrotic stricture is believed to be the cause of SVC syndrome as the computed tomography showed no definite hypodense material in the SVC and the symptoms persisted after anticoagulation. Our case demonstrates that angioplasty can treat SVC syndrome with mid-term success. The pacemaker function remained normal after angioplasty. We suggest that balloon angioplasty alone should be attempted first in patients with SVC syndrome if the stenotic lesion is dilatable, because restenosis may occur even after stenting and can be treated by repeating angioplasty. Stenting for all cases may be not necessary, but should be considered for refractory cases. Retraction of the old lead first should be done before stenting, as it may ameliorate the concern of possible lead damage and jailing. Bypass surgery should be reserved for those in whom angioplasty was failed, or whose leads are dysfunctional and have no feasible vascular access to place the new system. REFERENCES 1. Goudevenos JA, Reid PG, Adams PC, et al. Pacemaker-induced superior vena cava syndrome: report of four cases and review of the literature. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1989;12:1890-5. 2. Oginosawa Y, Abe H, Nakashima Y. The incidence and risk factors for venous obstruction after implantation of transvenous pacing leads. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2002;25:1605-11. 3. Kitamura J, Murakami Y, Shimada T, et al. Morphological observation by intravascular ultrasound in superior vena cava syndrome after pacemaker implantation. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1996;37:83-5. 4. Tan CW, Vijitbenjaronk P, Khuri B. Superior vena cava syndrome due to permanent transvenous pacemaker electrodes: successful treatment with combined thrombolysis and angioplasty ¾ a case report. Angiology 2000;51:963-9. 41 Acta Cardiol Sin 2008;24:39-42 Wen-Po Chuang et al. 5. Gray BH, Olin JW, Graor RA, et al. Safety and efficacy of thrombolytic therapy for superior vena cava syndrome. Chest 1991; 99:54-9. 6. Smayra T, Otal P, Chabbert V, et al. Long-term results of endovascular stent placement in the superior caval venous system. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2001;24:388-94. 7. Bolad I, Karanam S, Mathew D, et al. Percutaneous treatment of superior vena cava obstruction following transvenous device implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2005;65:54-9. 8. Lin CT, Kuo CT, Lin KH, Hsu TS. Superior vena cava syndrome as a complication of transvenous permanent pacemaker implantation. Jpn Heart J 1999;40:477-80. 9. Chan AW, Bhatt DL, Wilkoff BL, et al. Percutaneous treatment for pacemaker-associated superior vena cava syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2002;25:1628-33. 10. Wisselink W, Money SR, Becker MO, et al. Comparison of operative reconstruction and percutaneous balloon dilatation for central venous obstruction. Am J Surg 1993;166:200-4; discussion 204-5. Acta Cardiol Sin 2008;24:39-42 11. Doty DB, Doty JR, Jones KW. Bypass of superior vena cava: fifteen years’ experience with spiral vein graft for obstruction of superior vena cava caused by benign disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990;99:889-95; discussion 895-6. 12. Kataoka H. Ten-year follow-up of a patient with pacemaker induced superior vena cava syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1997;20:1734-6. 13. Schindler N, Vogelzang RL. Superior vena cava syndrome: experience with endovascular stents and surgical therapy. Surg Clin North Am 1999;79:683-94, xi. 14. Marzo KP, Schwartz R, Glanz S. Early restenosis following percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty for the treatment of the superior vena caval syndrome due to pacemaker-induced stenosis. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1995;36:128-31. 15. Oshima K, Takahashi T, Ishikawa S, et al. Superior vena cava rupture caused during balloon dilation for treatment of SVC syndrome due to repetitive catheter ablation: a case report. Angiology 2006;57:247-9. 42