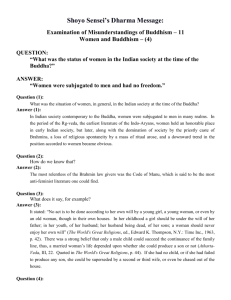

The Teaching of the Buddha

advertisement