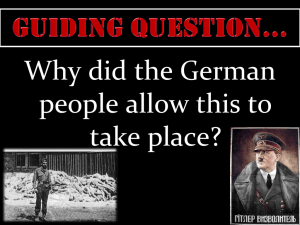

Propaganda in Nazi Germany

advertisement

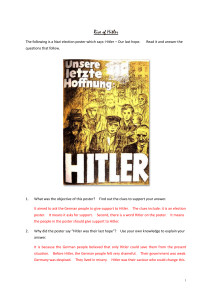

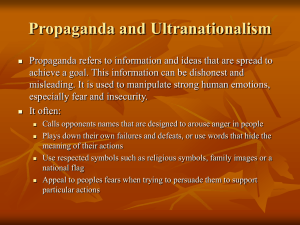

Propaganda in Nazi Germany The Nazis gained 52 per cent of the vote in the March 1933 elections. This government will not be content with 52 per cent behind it and with terrorising the remaining 48 per cent, but will see its most immediate task as winning over that remaining 48 per cent . . . It is not enough for people to be more or less reconciled to the regime. Goebbels at his first press conference on becoming Minister for Propaganda, March 1933. Propaganda and the “Fuhrer Myth”: A central theme in Nazi ideology and propaganda was the ‘Fuhrer Myth’. To disseminate from the other parties of the day, the Nazis felt one man was needed as the focal point of their campaign. This was to be the man on which Germany’s hopes and dreams rested and Adolf Hitler emerged as that man. His status as the ‘Fuhrer’ became the main focal point for Germany and the Nazis to rally around. The leadership of one was not lost upon Hitler himself. He realised ‘the most important part of fascism was trust in a wise and able leader’. His projection as a ‘charismatic superhuman’, destined to lead Germany to greatness was a significant fortes in German politics. It was not lost on the Party that to procure a permanent position in the German parliament public support was vital. Support for the ‘Fuhrer’ was paramount in all this. Before 1933: After the ‘Munich Putsch’ of 1923, military action was no longer viable in the current climate. To gain power the Nazis had to pursue a peaceful political route. A campaign was fought to perpetuate the Nazi Party, Adolf Hitler in particular, as the saviour of Germany. It would be through the ‘Fuhrer’ alone that the Nazis would be able to rid Germany of the grievances of the past and procure a new and powerful state. A state free from economic depression and safe from enemies at home and abroad. The ‘Hitler Movement’, as it was known even on the ballots of the time, was a carefully constructed propaganda coup. Images of the ‘Fuhrer’ were designed to show a ‘man of the people’. One who possessed charisma, heroism and respectability? It was all carefully crafted in such a way so as to portray to the German public a sense of invincibility. His simple attire portrayed in the visual material of the time however was a purposeful move instructed by the Nazi propaganda network. His role as the ex-serviceman helping Germany rise from the ashes is prominent in many posters and visual documents of the day. In this poster from the 1932 elections, “Hitler Becomes Reich President”, (Fig2.0), we see Hitler dressed in an ordinary outfit. He wears a suit and tie but still holds that mystique as he addresses the people shouting, “We are taking the fate of the nation in our hands!” The ordinary man leading his people is a common tool of early Nazi propaganda. “Hitler Becomes Reich President” (Fig2.0) 1932 election poster Also in this portrait by Hermann Otto Hoyer, (Fig.2.1), Hitler again features as the archetypical ‘man of the people’. Wearing his suit and addressing the crowd with a vehemence and power, they look upon him with adulation. His charisma and respectability are emphasized by his stature and pose in the portrait. The ‘Fuhrer Myth’ of early Nazi propaganda was all about displaying the ‘Fuhrer’ as the ordinary man, destined to fight and lead Germany to a better future. Hermann Otto Hoyer “In the Beginning Was the Word” (Fig 2.1) 1937 After 1933: The ‘Fuhrer Myth’ that began in the campaigns of the 1920’s and early 1930’s however paled in comparison to the image of the ‘Fuhrer’ once the Nazis seized power. Hitler was transformed from “the leader of a popular political party into the leader of all Germans”. He no longer strived to change Germany with words; he could now change Germany with actions. An inexorable amount of time was put into transforming Hitler into a more powerful figurehead than his previous portrayal. The simple attire of the exserviceman was forsaken and replaced by the militaristic style of a man in power. His image was refined to portray the ‘Fuhrer’ as Germany’s chosen saviour; a man destined by providence to lead Germany on the road to greatness. The powerful military image of Hitler was now imposed on the German nation. In the 1934 poster “Yes Fuhrer, We Follow You”, (Fig.2.2), Hitler wears a military uniform. The days of the simple suit are gone. Now it is all about power and might. The masses jubilantly call at his beckoning and the larger than life figure of Hitler epitomizes the ‘will of the people’. The stature, the cold stare, all play upon the images of old. Hitler often used the ‘Renaissance pose’ that mimicked the great leaders of the past, men such as Napoleon Bonaparte, Friedrich the Great and Otto von Bismarck. “Yes Fuhrer, We Follow You” (Fig 2.2) 1934 This signature pose is also clear in other posters such as the famous “One People, One Nation, One Leader!”, (Fig.2.3). It was this poster that became the common image of Hitler displayed throughout Germany once he came to power. Here again we have the ‘Renaissance pose’ and the cold collecting stare. In many homes across Germany this image of Hitler became the equivalent to a religious icon. It was held higher than the crucifix or a holy painting. The portrait was put up in homes, classrooms and offices across the country. The image of the Fuhrer was fast becoming the image of the new messiah. “One People, One Nation, One Leader!” (Fig 2.3) 1938 As a result the “Hitler Myth” became a kind of religion, Mein Kampf, the new household bible. In fact over ten million copies of Mein Kampf had been published by 1945. “Like the family Bible, it was often unread, but its mere presence testified to its importance. The idea of the Fuhrer as the new messiah appealed to many. In the words of one German soldier, ‘Our Fuhrer is the most unique man in history. I believe unreservedly in him. He is my religion. This is a testament to the power and sway Adolf Hitler held. From now on the visual representation of Hitler in poster design re-enforces this notion. Post 1933 political posters are substantially different than their predecessors. This is none more evident than in figure 2.4, “Long live Germany”, where Hitler is now characterised as a religious icon. The poster displays direct connotations with religious art and folklore from the bible. Hitler is seen leading his people forward, holding the banner of National Socialism. The rays of sunshine that light his way re-enforce his metaphoric presence as a man of destiny. The eagle in the background is in direct contrast to the angel used in many religious paintings. A direct connotation is made, substituting Hitler as a new messiah. “Long live Germany” (Fig 2.4) Russia’s Two Leaders, Iconography of the Vozhd’: The iconography of the vozhd’ in Russian visual propaganda deals in much the same way to that of the Nazis. A common theme to both dictatorships of course was the ‘cult of the leader’ and this began in Russia in the very early days of the Bolshevik revolution. The term vozhd’ was originally a military term for leaders in the revolution but soon became the standard term to describe all party leaders in the Bolshevik hierarchy. As the decade progressed however the term was more often applied to Lenin and later Stalin. The name held the same connotations as ‘Der Fuhrer’ in Germany and was a title regarded with honour. As with Nazi Germany, the “cult of the leader” became a huge focal point for Russian propaganda artists. The Worker in Nazi Society: The Nazi’s seizure of power in 1933 was more than a change of government it was the beginning of radical ideological shift in German society. In accordance with Nazi ideology the population of Germany was to be re-educated based on National Socialist values and key to this was the creation of Volksgemeinschaft, meaning ‘national community’. The so-called ‘national community’ was a restructure of German society bypassing class, religion and regional loyalty. The creation of a racially pure ‘Aryan’ community Hitler believed would bring about a new heightened national awareness. Inevitably it would be Nazi propaganda that would become crucial in selling this view, as ‘Propaganda was intended to be the active force cementing the national community together’. Subsequently poster design was one of the main forces behind this venture. It was under the common banner of the above-mentioned Volksgemeinschaft that labour existed in Germany. Trade Unions were abolished, as Hitler believed they displayed left-wing socialist connotations representative of the class struggle. As a result the German Labour Front was set up in 1933 to act as an ‘honest broker’ between the classes’. The Labour Front was formed so as to masquerade and hide the fact that workers rights had been diminished. Posters proclaimed, ‘Workers will stand side by side with employers’, trying in vain to appeal to the emotions of the common man. In visual iconography of the time, the German worker was predominantly male. He is often depicted in a strong resolute pose characterising the ideals of the perfect ‘Aryan’ male. As in Russian propaganda the male worker is often shown as a larger than life figure as shown in the 1932 election poster “We Workers Have Awakened, We’re Voting National Socialist”, (Fig.3.0). The figure stands tall above Germany’s supposed enemies, (Jews and Marxists). Through the strength of German labour we are led to believe the values of National Socialism will be withheld and pursued. “We Workers Have Awakened, We’re Voting National Socialist” (Fig 3.0) 1932 Nazi propagandist’s also tried to evoke the values of ‘national community’ by conveying that German workers were part of a collective regardless of their standing in society. This is evident in posters such as this one from the German Labour Front, (Fig.3.1), where all German workers, just like soldiers, were comrades in the eyes of Germany. Linking the German Labour Front to WW1 (Fig 3.1) 1933 Felix Albrecht also displays this viewpoint in another 1932 election poster entitled, “Workers of the Mind and of the Fist, Vote for the Front Soldier Hitler” (Fig.3.2). The image combines both facets of the industrial workers ‘of the fist’, and ordinary workers ‘of the mind’. Interestingly the poster refers to Hitler’s military service in the Great War, possibly as in figure 3.1 to promote the idea of comradeship amongst all walks of German life; again the so-called Volksgemeinschaft. Felix Albrecht, “Workers of the Mind and of the Fist, Vote for the Front Soldier Hitler” (Fig 3.2) 1932 Women in Nazi Society: Women played a rather contrasting role in Nazi society. On the one hand women were celebrated and viewed as the key in providing Germany with a racially pure ‘Aryan community’, yet they were still seen as inferior in the eyes of many leading Nazis. The Nazi party was undoubtedly anti-feminist, in fact Hitler vowed in 1932 to remove 800,000 women from employment. He believed that women’s rights, and the term emancipation was a slogan adopted by Jewish intellectuals to corrupt the pure German nation. Hitler stated that for the German woman her ‘world is her husband, her family, her children and her home’. Joseph Goebbels the Nazi Propaganda Minister even proclaimed, “Women have the task of being beautiful and bringing children into the world”. It is surprising how stark these comments were considering the Nazi party needed female votes in early electoral campaigns. Clearly the ‘new woman’, the ‘cigarette smoking, motorbike riding, silk stockinged or tennis-skirted young woman’, who was free spirited and independent did not coincide with Nazi ideology. Instead a woman’s role was the family and the home, (Fig.3.7). Women played a key role in Nazi thinking. The need for increased birth rates due to the inevitability of war was a big part of Hitler’s overall plans. Hitler believed ‘the woman has her own battlefield, with every child she brings into the world; she fights a battle for the nation’. The focus of females in Nazi society was on childbirth and domesticity. In this poster, (Fig 3.8), by the Nazi charitable organisation the NSV, the role of women in Nazi Germany is clear. The text reads ‘Support the assistance program for mother and child'; however it is the visual layout that is striking. The woman is dressed idyllically in a blue gown, cradling a baby in her arms. She epitomizes the ideal Aryan woman, blond haired, who is strong and purposeful. The addition of the character ploughing in the background imposes the role women should play. Their job is at home looking after the family, not the workplace. This stereotypical role was compounded when even leading Nazi women, such as Gertard Scholtz-Klink, head of the Nazi Women’s League felt “the mission of women is to minister in the home”. Enemies in Nazi Poster Design: A specific theme in early Nazi poster campaigns was the grand notion that Germany’s enemies had harnessed the so-called ‘stab in the back’. This miss-conception, which Hitler called, ‘the greatest villainy of the century’ led many to believe Germany had lost the Great War specifically due to enemies at home. The poster shown below, (Fig 3.12), from a 1924 election campaign for the German Nationalist People’s Party by Hans Schweitzer conveys the sentiments of the ‘stab in the back’. It vividly depicts a German soldier physically getting knifed from behind and the enemy is evidently a Bolshevik due to the fact he is dressed in red. Hans Schweitzer, German Nationalist People’s Party election poster (Fig 3.12) 1924. This theme of connecting Germany’s defeat to Bolshevism after World War One was common in early Nazi poster design as this poster from 1919 entitled “The Danger of Bolshevism” clearly shows, (Fig 3.13). The caption says it all, but it is the knife in the skull-like figures mouth that subtly conveys the ‘stab in the back’ message. Rudi Feld, “The Danger of Bolshevism” (Fig 3.13) 1919. As one can see, the Bolsheviks were a key enemy figure in Nazi visual imagery and it remained that way right throughout Hitler’s reign. Obviously the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 kept this theme running. And after the catastrophe of Stalingrad in 1943, the Nazi Propaganda Office issued extreme directives concerning antiBolshevik propaganda, which declared Bolshevism as its main enemy. This poster circa February 1943 entitled “Victory or Bolshevism”, (Fig 3.14), shows quite clearly the choice Germany must face. Hans Schweitzer, “Victory or Bolshevism” (3.14) 1943. One enemy type in particular that faced special vilification in Nazi propaganda was the Jew. Hitler’s belief in a worldwide Jewish conspiracy, spurred on by Bolshevism, (Fig 3.15 shows a poster for the film “The Eternal Jew” depicting the satirical image of a Jew holding a map of the world displaying the Soviet emblem of the Hammer & Sickle), meant Germany became the mainstay for antiSemitic imagery across Europe, albeit what began at first as antiSemitic rhetoric later turned into fullscale murder in the form of the Holocaust. Hans Staluter, “The Eternal Jew” (Fig 3.15) 1937. ‘All of Germany’s problems are the fault of the Jews!’ This quote from Joseph Goebbels sums up Germany’s position on the Jewish question. They became scapegoats for everything that was wrong and later went wrong when Germany finally went to war in 1939. The Jewish population were continuously characterised in satirical fashion, and caricatures often portrayed them with a large nose and top hat much like the capitalists portrayal in Stalinist Russia. The poster below states, “He is to Blame for the War”, (Fig 3.16), and is a typical depiction of a Jew in Nazi Germany at this time. Once again this poster proclaims it is the fault of the Jews for starting the war. In fact Nazi propagandist’s continuously blamed the Jews for nonsensical and fanciful things such as the bombing of German cities and the disastrous situation Germany faced at the front. Their depiction as skulking figures, something beyond human became a common tool in downgrading their status and made anti-Semitic rhetoric easier to swallow. For Adolf Hitler eliminating the Jews became a goal he obsessed over beyond even winning the war. Poster campaigns demonising Jews and showing them as something beyond human was a prelude to genocide and made the job of mass murder a whole lot simpler. Hans Schweitzer, “He is to Blame for the War!” (Fig 3.16) 1943 Enemies in Soviet Poster Design: Demonology of the enemy in Soviet poster design consisted of two basic elements; internal enemies at home such as the Tsar, Church and Kulak and external enemies abroad, such as foreign capitalists or other unfriendly nations. As previously discussed figureheads such as Lenin formed the basis for heroism yet enemies were needed too. The Bolsheviks felt the masses needed a clear indication of who to trust and who to follow. As a result three key enemy figures soon emerged in Bolshevik demonology. These were the Tsar, the priest (church) and the kulak, (wealthy peasants who represented the ‘class’ struggle). A very early example of this can be seen in the 1918 poster “Tsar, Priest & Kulak”, (Fig 3.17). The Tsar is shown centre stage in-between the priest and kulak. His crown and various other royal accessories clearly distinguish him as royalty. The kulak, with cap and beard, stands facing the tsar, (possible reference to the kulak being in the tsar’s financial pocket). The priest stands left of the tsar and is clearly recognisable by his skullcap and cross. The priest wears an all-together more evil expression then either the tsar or kulak. His snarling teeth portray him in a demonic light. The church is clearly being noted for special vilification. It was through posters such as this that the Bolsheviks pinpointed enemies of the state. While the image of the priest or kulak changed with time, (sometimes portrayed wearing differing styles of clothes, expressions etc.), this 1918 poster designated three specific internal enemies opposed to the new regime and its future.