Redefining Searches Incident to Arrest: Gant's Effect on Chimel

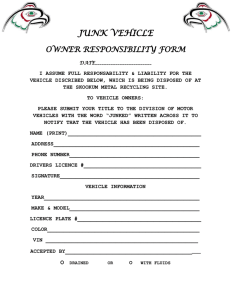

advertisement