Media Law Bulletin, November 2005

advertisement

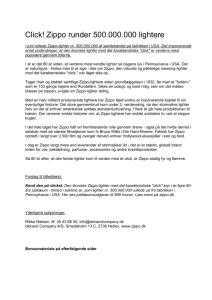

Media Law BULLETIN November 2005 E-Commerce and the Advent of Jurisdiction Based on Internet Contacts The Internet – “Big Business” With Internet commerce, many businesses have learned a hard lesson about the consequences of doing business as “e-merchants,” primarily in the form of being forced to face litigation in jurisdictions they would never set foot in as a “brick and mortar” business. As the Ninth Circuit so aptly stated, “It is increasingly clear that modern businesses no longer require actual physical presence in a state in order to engage in commercial activity there. With the advent of ‘e-commerce,’ businesses may set up shop, so to speak, without ever actually setting foot in the state where they intend to sell their wares.”1 This e-commerce is big business. According to a January 2004 estimate, online sales, in the United States alone, were anticipated to reach $65 billion by the end of 2004, with growth expected to continue at a compound annual rate of 17% through 2008 to $230 billion. This study also estimated online growth, in the United States, was expected to grow 14% in 2005. This figure is equivalent to 30% of the entire U.S. population. Many believe that by 2008 approximately one-half of the U.S. population will make at least one online purchase a year. Jurisdiction 101 – The Basics of Jurisdiction in the United States As the previous figures demonstrate, online purchases are rapidly becoming a preferred means of shopping. Online retailing in the United States is a [ Highlighting legal issues affecting the media and entertainment industries ] multibillion-dollar industry in which an unsuspecting online retailer could face jurisdictional issues in all 50 states. Therefore, it is increasingly important for online merchants and retailers to understand the basics of jurisdiction in the United States before embarking on an e-commerce venture. Jurisdiction is the power of a court to render a decision that will be recognized and enforced by authorities and other courts. There are two types of jurisdiction, subject matter jurisdiction and jurisdiction over the parties – or personal jurisdiction. A court must have both subject matter and personal jurisdiction before it can consider the case.2 Personal jurisdiction is the power of a court to adjudicate the personal legal rights of parties properly brought before it.3 To establish personal jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant, the plaintiff must satisfy both constitutional due process requirements and the requirements of the given state’s long-arm statute.4 Many state longarm statutes authorize a court to exercise jurisdiction over a nonresident defendant on any basis not inconsistent with the U.S. Constitution or the state constitution,5 which in most cases requires that a defendant have sufficient “minimum contacts” with the state, such that maintenance of the suit does not offend “traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.”6 Once the court determines that there are sufficient “minimum contacts,” a defendant then becomes subject to either specific or general personal jurisdiction.7 General jurisdiction is asserted if the non-resident defendant conducts “substantial” or “continuous and systematic” activities in the state, whether or not those activities give rise to the plaintiff’s complaint.8 A finding of general jurisdiction requires a higher level of “contacts” with the forum state.9 Specific jurisdiction, on the other hand, is proper if the case arises out of certain forum-related acts or if the defendant’s out-of-state activities were purposefully directed toward a state resident and caused injury.10 When exercising either general or specific jurisdiction over a nonresident defendant, the overriding principle is that the defendant must have purposefully availed itself of the privilege of conducting activities in the forum state, thus invoking the benefits and protections of its laws.”11 The purposeful availment requirement ensures that a defendant will not be hauled into a jurisdiction solely as a result of “random,” “fortuitous,” or “attenuated” contacts.12 As with general jurisdiction, the assertion of specific jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant must be reasonable to comport with constitutional due process requirements. Acts that have satisfied the “purposeful availment” requirement include directing a magazine article at the forum residents;13 placing goods into the stream of commerce;14 and nationwide advertising.15 Media Law Bulletin is a consistently relevant, frequently irreverent, and potentially entertaining monthly publication written and edited by Sedgwick’s Los Angeles-based Media Law Group. To receive future editions by e-mail, drop a line to james.holmes@sdma.com. [ 2 ] November 2005 Media Law Bulletin Sedgwick, Detert, Moran & Arnold LLP © 2005 Sedgwick, Detert, Moran & Arnold LLP [ www.sdma.com ] 5 Zurich 4 San Francisco 3 This communication is published as an information service for clients and friends of the firm and is made available with the understanding that it does not constitute the rendering of legal advice or other professional service. Paris 2 Gator.com Corp. v. L.L. Bean, Inc., 398 F.3d 1125 (9th Cir. 2003). See Ruhrgas AG v. Marathon Oil Co., 526 U.S. 574 (1999). International Shoe Co. v. State of Washington, 326 U.S. 310 (1945). Id. See, Cybersell, Inc. v. Cybersell, Inc., 130 F.3d 404 (9th Cir. 1997) (Arizona Orange County 1 Newark Footnotes Media Law Bulletin is published by Sedgwick, Detert, Moran & Arnold LLP. For copies of the cited cases, or any other assistance, please contact James J.S. Holmes, Esq. or John F. Stephens, Esq. at (213) 426-6900 or send an e-mail to james.holmes@sdma.com or john. stephens@sdma.com. New York By John Stephens and Stacy Goldscher Media Law Bulletin Los Angeles Analyzing whether these primarily Internet-based contacts supported a finding of “minimum contacts” and the assertion of personal jurisdiction, the court noted that the Internet made it possible to conduct business worldwide entirely from a desktop and that a new rule was necessary to evaluate “minimum contacts” over the Internet. The court ruled that the “likelihood that personal jurisdiction can be constitutionally exercised is directly proportionate to the nature and quality of commercial activity that an entity conducts over the Internet.” Each state is free to set its own requirements for personal jurisdiction subject to federal constitutional limits of due process. A circuit-by-circuit survey of jurisdictional decisions analyzing Internet-based personal jurisdiction reveals that, although it is clear that not all U.S. courts have adopted the Zippo test, the key issue in the jurisdictional arena is the nature and quality of Internet contacts between the defendant and the forum state.17 The stronger the contacts, the more likely a court will be to assert personal jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant. Therefore, this is an issue that a merchant must keep in mind when setting up its website. London In analyzing the issue, the court noted that Zippo Dot Com’s contacts with Pennsylvania occurred almost exclusively over the Internet, and it had no offices, employees or agents in the state. Moreover, the only advertising it conducted involved information posted on its web page. Of its approximately 140,000 subscribers, approximately 2% were Pennsylvania residents. Finally, Zippo Dot Com had entered into agreements with seven Internet service providers in Pennsylvania to permit their subscribers access to the news service. long-arm statute); L.L. Bean v. Gator. Com, 2003 DJDAR 10023 (California long-arm statute); McGill Technology Ltd. v. Gourmet Technologies, Inc, 300 F.Supp.2d 501 (E.D. Mich. 2004) (Michigan long-arm statute); Mink v. AAAA Development LLC., 190 F.3d 333 (5th Cir. 1999) (Texas long-arm statute). 6 International Shoe Co. v. State of Washington, 326 U.S. 310 (1945). 7 See Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462 (1985); Helicopteros Nacionales de Columbia, S.A.v. Hall, 466 U.S. 408 (1984). 8 Helicopteros Nacionales de Columbia, S.A.v. Hall, 466 U.S. 408 (1984). 9 Data Disc, Inc. v. Systems Technology Assocs., Inc., 557 F.2d 1280, 1287 (9th Cir.1977); Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. v. Robertson-Ceco Corp., 84 F.3d 560 570571 (2d Cir. 1996). 10 Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462 (1985). 11 Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U.S. 235 (1958). 12 Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462 (1985). 13 Calder v. Jones 465 U.S. 783 (1984). 14 World Wide Volkswagen v. Woodson, 444 U.S. 286 (1980). 15 United States SEC v. Carrillo, 115 F.3d 1540, 1545 (11th Cir. 1997). 16 952 F.Supp.1119 (W.D. Pa. 1997). 17 A chart tracking the test used in each federal circuit for assertion of personal jurisdiction based on Internet activities is available for download from our website, at www.sdma.com/medialaw/ circuitchart.pdf. Dallas The benchmark case dealing with Internet jurisdiction is Zippo Manufacturing v. Zippo Dot Com.16 Zippo Manufacturing is a Pennsylvania corporation that manufactures “Zippo” lighters, and holds the trademark on the name “ZIPPO.” Zippo Dot Com, Inc. is a California corporation, that operates a website, an Internet news service and held the rights to the domain names “zippo.com,” “zippo.net” and “zipponews.com.” Zippo Manufacturing brought suit against Zippo Dot Com alleging that it had violated the Federal Trademark Act and various other Pennsylvania state intellectual property laws. Zippo Dot Com moved to dismiss the action on the grounds that the court lacked personal jurisdiction. Accordingly, the court developed a sliding scale to determine personal jurisdiction over non-resident defendants. At the extreme end, a website that is fully interactive and acts as a virtual storefront suggests jurisdiction will almost always be proper. At the other end, a completely passive website that simply provides information to the end user, without any opportunity for interaction with the owner of the site, suggests the contacts will likely never be sufficient for a finding of jurisdiction. For cases in the middle of the spectrum, (i.e., where the user just exchanges information with the website), the court found that “the exercise of jurisdiction is determined by examining the level of interactivity and commercial nature of the exchange of information that occurs on the web site.” The court concluded that Zippo Dot Com’s activities in Pennsylvania were sufficient to satisfy the court’s exercise of personal jurisdiction. Chicago Zippo Mfr. Co. v. Zippo Dot Com, Inc. – Setting the Benchmark for Internet-Based Exercise of Personal Jurisdiction SEDGWICK | MEDIA LAW BULLETIN | NOVEMBER 2005 Eight Years After Zippo: A Circuit-by-Circuit Look at Personal Jurisdiction Zippo Mfr. Co. v. Zippo Dot Com, Inc., 952 F.Supp.1119 (W.D. Pa. 1997) FOLLOWS ZIPPO MODIFIES ZIPPO DEVELOPED OWN TEST Second Circuit First Circuit Fourth Circuit Inset Systems Inc. v. Instruction Set, Inc., 937 F.Supp. 161 (D. Conn. 1996) Digital Equipment Corp. v. Alta Vista Technology, Inc., 960 F.Supp. 456 (D. Mass. 1997) ALS Scan, Inc. v. Digital Service Consultants, Inc., 293 F.3d 707 (4th Cir. 2002) Third Circuit Zippo v. Zippo Dot Com, 952 F.Supp.2d 1119 (W.D. Pa. 1997) Fifth Circuit Mink v. AAAA Development LLC, 190 F.3d 333 (5th Cir. 1999) Sixth Circuit Neogen Corp. v. Neo Gen Screening, Inc., 282 F.3d 883 (6th Cir. 2002) Seventh Circuit D.C. Circuit Jennings v. AC Hydraulic A/S, 383 F.3d 546 (7th Cir. 2004) GTE New Media Services, Inc. v. Ameritech Corp., 21 F.Supp.2d 27 (D.D.C. 1998) Tenth Circuit Intercon, Inc. v. Bell Atlantic Internet Solutions, Inc., 205 F.3d 1244 (10th Cir. 2000) Eleventh Circuit Nida Corp. v. Nida, 118 F.Supp.2d 1223 (M.D. Fla. 2000) Eighth Circuit Lakin v. Prudential Securities, Inc., 348 F.3d 704 (8th Cir. 2003) Ninth Circuit Gator.com Corp. v. L.L. Bean, Inc., 341 F.3d 1072 (9th Cir. 2003) This chart was prepared by John Stephens and Stacy Goldscher as a reference to their article, “E-Commerce and the Advent of Jurisdiction Based on Internet Contacts,” published in the November 2005 issue of Sedgwick’s Media Law Bulletin. Media Law Bulletin is published by Sedgwick, Detert, Moran & Arnold LLP. For copies of the cited cases, or any other assistance, please contact James J.S. Holmes, Esq. or John F. Stephens, Esq. at (213) 426-6900 or send an e-mail to james.holmes@sdma.com or john.stephens@sdma.com. © 2005 Sedgwick, Detert, Moran & Arnold LLP. This communication is published as an information service for clients and friends of the firm and is made available with the understanding that it does not constitute the rendering of legal advice or other professional service.