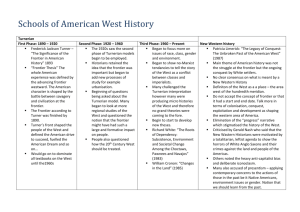

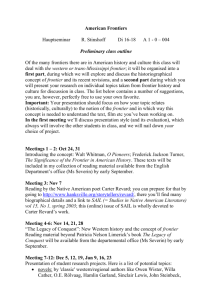

The Significance of the Frontier in American History

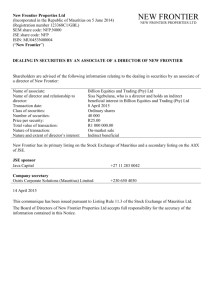

advertisement